20 YEARS OF M2: A Retrospective Look At How To Make It In The World

To say the world has changed a lot in twenty years is an understatement. When we first got started in 2005 we had no idea we were just a few years away from a global financial crisis, then a pandemic and then a resurgence in cold war saber rattling. We didn’t know what cryptocurrency was and could hardly imagine rockets would be making controlled landings after sending commercial programs to space. Smartphones hadn’t made a splash with consumers and we were perfectly happy with our ADSL connections if we were fancy. You couldn’t judge potential partners with a single swipe and nobody was letting Jesus take the wheel in their electric cars. Was it a simpler time? No. You had to have a proper GPS or know how to actually read a map to get anywhere. Or, shock horror, just memorise where your best friend lived.

This isn’t as upbeat as I was intending. Let’s nip this in the bud and take a look at how the world has changed in the last twenty years, and how to survive in it.

2005

The year is 2005 and Clint Eastwood has just pulled his Oscar for Million Dollar Baby. The Airbus A380 has just been unveiled as the largest commercial jet in the world and Youtube is making it’s first staggering steps into the world like a newborn fawn. Tony Blair and George W bush are in power double teaming Iraq for all those weapons of mass destruction they totally have (trust me bro) and in Helen Clark’s New Zealand it’s the perfect time to release a new magazine. M2 puts out its first issue with Clint Eastwood as their cover man using a picture that looks like it had been taken 30 years prior.

20 Years of Pak’n Save

This magazine is mostly about cool watches, cool people and cool cars. Pak’n Save is antithetical to a lot of this, but we’re also a business mag and celebrating success and that is something Pak’n Save has in spades. I was always told growing up that the Henderson Pak’n Save mum dragged me through was the first one. In fact it was the second by a few months, the first one was started in 1985 in Kaitaia by Gaylene Voss and her husband Barry. The pair had run a Four Square before Foodstuffs approached them about building a larger food store for families looking to buy in bulk on a monthly basis. It’s top selling items were candles and mutton. Bus trips were organised to the store and Gaylene knew they were going gangbusters when she realised she didn’t know how many zeroes to use for “3 million dollars” when doing their third expansion for a bakery. There are now 58 stores and the brands commitment for no frills and good prices remains to this day, as it is consistently the cheapest place to get groceries.

Youtube

2005 was the year YouTube exploded into our lives – and good job too as it let us watch Janet Jackson’s ‘wardrobe malfunction’ during the Superbowl Halftime Show as much as we needed! Created by Chad Hurley et al, YouTube was all about giving users the chance to share their videos by uploading them onto a shared space. Something that seems so routine these days but was a whole new concept back in 2005!

The key to YouTube’s success was that it got rid of the dreaded ‘gatekeepers’ of traditional media who, until then, were they only ones who could decide what videos were ‘worth sharing’ with us uneducated masses. This democratisation of content encouraged everyone to sing, play guitar, film their friends or re-edit movies and then upload it. So, if you had a computer and a camera (this was pre-smartphone, remember) your talents could be shared with the rest of the world – immediately.

Google could certainly see the potential benefits of having a global userbase and snapped it up for a cool $1.65 billion and immediately set about scaling YouTube’s infrastructure, improving the streaming quality, and expanding the services. The introduction of the Partner Program allowed creators to monetise content, fostering a whole new concept of influencers and online entrepreneurs to follow.

Like them or loathe them PewDiePie, Justin Bieber and Psy of ‘Gangnam Style’ fame owe their massively successful careers to YouTube. But it’s not just the famous who have benefited, YouTube has also given us the freedom to share our mate’s 21st yardie and our daughter’s first steps with friends and family instantly on the other side of the world. You can see that we certainly have done so with the mind-blowingly huge YouTube usage figures of over 2 billion monthly users, with 500+ hours of content uploaded every minute.

Even though other social media platforms have come and gone since 2005, YouTube remains indispensable to our digital culture, remaining the ultimate opportunity to ‘Broadcast Yourself.’

Reddit has become a mainstay institution of the internet, aggregating content as it desperately tries to pivot to being the originator of it. It’s one of the few places that even retains a whiff of the BBS board days of the old web.

An old email between cofounders Alexis Ohanian to Steve Huffman shows the excitement Alexis had for the idea. His spelling is also atrocious.

“i’m in singapore at this technepreneurial seminar, and am basically spending a week learning how to create a tech start-up.i spoke to Mark White (a professor in the comm school, the guy who took me to South Africa, and who recruited me to come here, as well as a generally good guy and technophile) over some drinks last nite, and pitched him on our idea…from his feedback-and let me remind you that he gets pitches every couple of months from students, and was very candid and honest with his thoughts, but basically said it was one of the best he’s heard, period… But the potential he saw was in the millions my friend… honestly, this is the kind of thing that could change our lives-and his motivation has really spurred me. but i need you and the same kind of commitment.”

Alexis Ohanian is now worth $150 million.

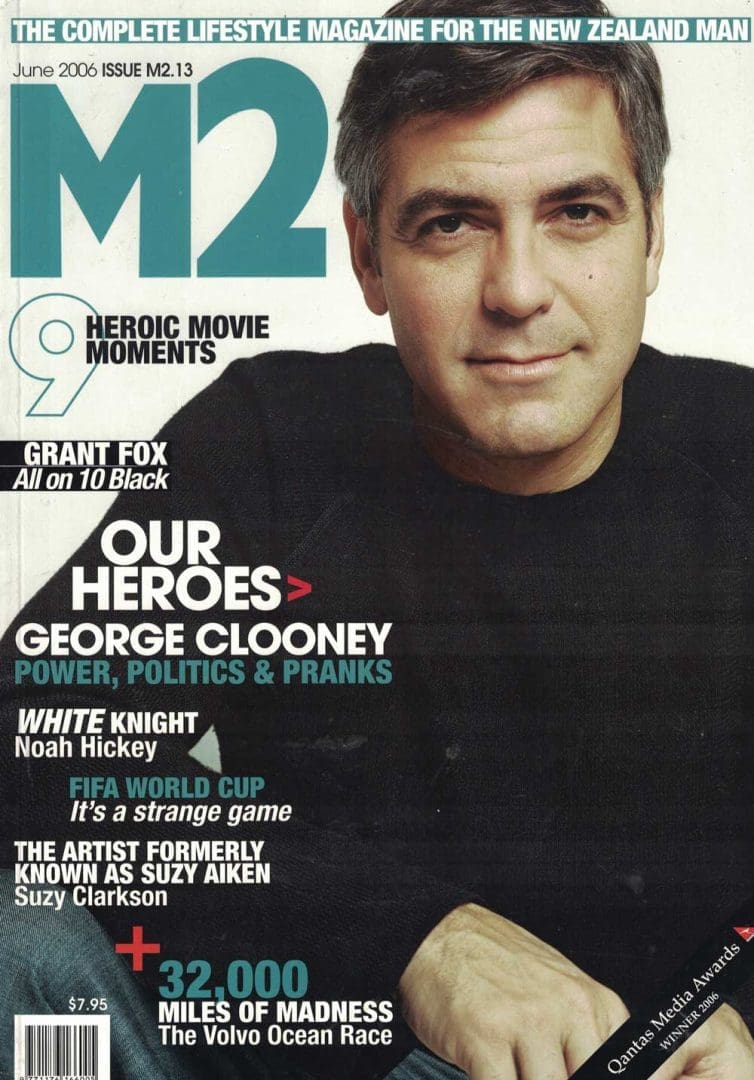

2006

In 2006 George Clooney was sitting pretty with his Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in Syriana alongside Matt Damon and Chris Cooper.

In our second year of print Enron former Chief Executive Jeffrey Skilling and founder Kenneth Lay went to trial and were found guilty of conspiracy and fraud. Tragedy also rocked australasia and the rest of the world when we lost Steve Irwin.

Grinding Gears Games

New Zealand’s gaming scene has been steadily growing over the decades but perhaps one of our most prolonged success stories is Grinding Gears Games, creators of the prolific Paths of Exile. PoE has successfully taken huge bites out of the king of dungeon crawlers Diablo, made by Blizzard, a titan of the industry responsible for World of Warcraft. Though they were founded in 2006 they wouldn’t release PoE until 2013. It was a great success and has been continually maintained up to today. PoE2 is currently in early access and I can confirm that it is a certified banger of a game, successfully iterating on everything that made the original title great.

The all encompassing Tencent bought a majority share in GGG in 2018. The remaining shares held by co-founders were finally relinquished to Tencent in 2024 in what I presume was a high tide mark for the company. I hope they enjoy their private islands, they deserve it.

2006 was the year Jack Dorsey launched Twitter as a microblogging program where users could share 140-character ‘tweets’. This posting of short, real-time updates proved revolutionary with its austere character limit encouraging concise and impactful messaging. Additional features such as hashtags and retweets plus its use by celebrities such as Oprah and Barack Obama transformed it into a global conversation hub. So much so, that by 2009, it was handling over 2.5 million tweets daily.

But it was its role in breaking hot news that really saw Twitter explode as a communication tool. Its role in spreading the word during the 2009 Iran protests and in 2011 Arab Spring saw Twitter become regarded as the ‘people’s news network.’

The #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements shifted Twitter beyond the ‘breaking news’ aspect as it became the platform for public discourse on social events and trends while also giving celebrities, brands, and politicians a direct line to their audiences. Monetisation strategies, such as Promoted Tweets and targeted advertising came in turning Twitter into a profitable enterprise – leading to a successful IPO in 2013 and over 330 million monthly active users a few years later.

Twitter was now so successful as a communication tool it became a ‘must-have’ for the right wing seeking to combat what they saw as a clear left wing bias in the mainstream media. Cue its purchase by Elon Musk. Despite his infantile rebranding of Twitter to ‘X’, the platform’s core function as a real-time public square still remains unmatched. In 2024 it became the only official place Biden announced his withdrawal in writing.

Today, Twitter – or X if you’d prefer! – has provided a lasting challenge to traditional media in shaping global conversations. Its legacy of democratising communication has left an enduring stamp on media, politics, and culture – and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

For his own part in it, Jack Dorsey still retains 2.4% in X, and is now on the board for Bluesky Social, which is attempting to be a decentralised version of X, similar to Mastadon.

2007

Rocket Lab

Founder Peter Beck wanted to make rockets, so he made rockets. Who cares that he wasn’t at NASA, let’s just get it done. Three years after it’s founding Rocket Lab would become the first private company in the southern hemisphere to reach space, aided by it’s rocket Ātea-1. The company found it’s niche by working on low cost rockets able to deliver cubesats into orbit. More American funding and a need to be closer to suppliers and buyers led the company to move a lot of it’s operations to the USA, but of the 2000 staff 700 of them are still here working in New Zealand and doing launches. Their contracts since have kept getting bigger and their sights have grown longer. Rocket Lab plans on being the first private company to reach Venus with an expected launch date of their Venus Life Finder probe in 2026.

Sir Peter Beck is now worth over $US1billion.

Reinventing cricket

2007 was the year cricket’s Indian Premier League (IPL) was approved by India’s governing body (BCCI) – and it changed the dour face of cricket forever. Twenty20 cricket had been around for a few years already – including its predecessor Martin Crowe’s Cricket Max! – but it was mainly played in international form. Nobody really took it that seriously either, viz the silly hairstyles and costumes of the infamous NZ/Australia clash in 2005 when the Marshall twins backcombed their hair up like they were going to a ‘70s disco.

The IPL wasn’t quite as loose as that yet it was a heck of a lot more fun than Test cricket – and that was a big, big part of its huge success. The Indians played loud music and had cheerleaders dancing with every six hit. The teams were stacked with internationals – but this time they weren’t all from the same country. Sourav Ganguly played alongside Ricky Ponting and Brendon McCullum for Kolkata while Wasim Jaffa batted with Jacquez Kallis and Virat Kohli for Bangalore. Franchise cricket had arrived!

Kiwi McCullum’s legendary swashbuckling century in the inaugural match a few months later set a tone that has pervaded ever since drawing massive crowds and lucrative broadcasting deals. The IPL has changed the way players interact with their own national boards too. Veteran players are able to extend their careers and younger players become accustomed to intense pressure match situations a lot earlier in life.

The IPL’s NFL Draft style player auction, fantasy player competitions like Dream11 and Bollywood star appeal have inspired such fan interaction outside the stadiums other countries have been eager to replicate the IPL’s success. Now there is the Big Bash League (BBL) in Australia, the Pakistan Super League (PSL), SA20 in South Africa and the Caribbean Premier League, making franchise cricket a year-round spectacle. Ultimately, the IPL’s success has not just changed cricket—it has redefined the modern sports industry.

Weta Workshop

Founded in 1987 by Richard Taylor and Tania Rodger RT Effects would have plenty of work making props for the likes of Hercules and Xena as well as Meet the Feebles in the 80s and 90s. By the time they were celebrating their 20th anniversary in 2007 they had ascended to being perhaps the most famous VFX studio in the world after all their incredible work on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. To this day they are doing movie magic with their most recent credits including the puppetry in Alien: Romulus, the Dune movies, and… The Minecraft movie? Ok then.

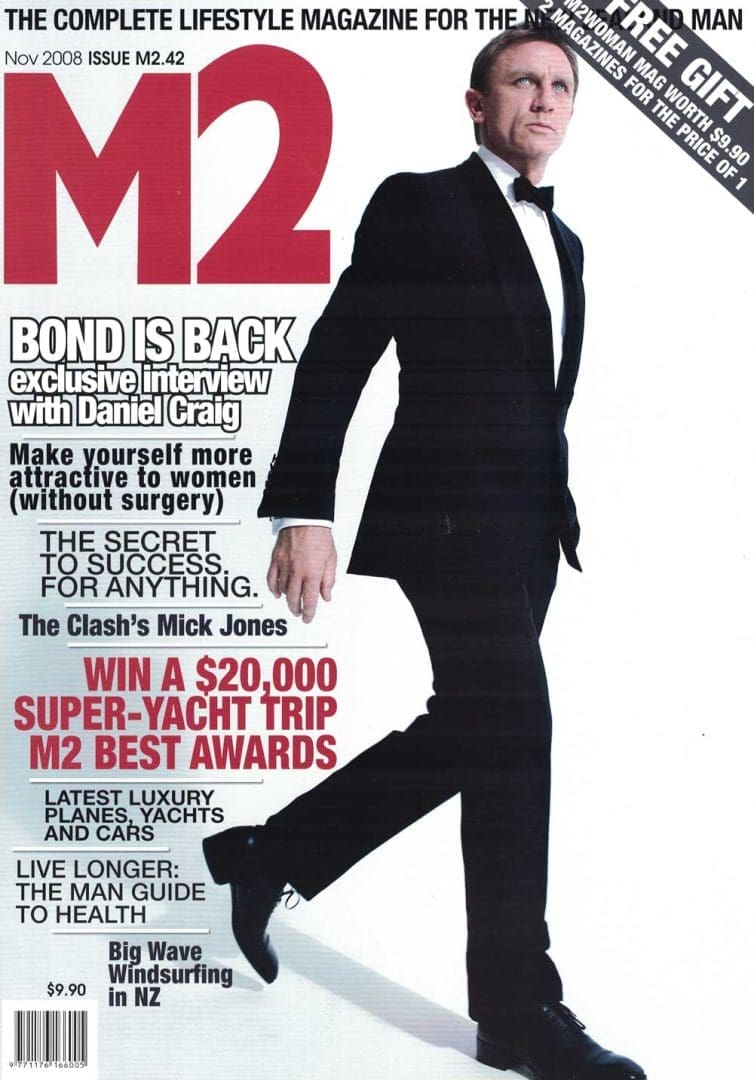

2008

It was an election year for New Zealand in 2008. Helen Clark gave it a half hearted attempt but really had her eye on bigger and better things over at the UN. John Key landed the gig just in time to sail the country through the stormy GFC seas. The Online hacker collective Anonymous got it’s start after the Church of Scientology Copyright striked a leaked interview of Tom Cruise on the fresh faced Youtube. Bhutan got it’s first election after the king abdicated and turned the country into a democracy. If you want a glimpse into this time watch The Monk And The Gun. It’s a sweet little movie.

Marvel At That

2008 was the debut year of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and a lesson in forward planning and betting the farm on a good idea. Marvel had just struggled it’s way out of bankruptcy and didn’t look like it had a strong hand to play with. All it’s major properties had already been leased out to other studios. All they had were B-grade heroes like Thor and Ironman, who at the time weren’t exactly on the same level as X-Men and Spiderman. We got Iron Man and The Incredible Hulk. Expectations were that Hulk would do better due to name recognition and Iron Man would be middling, but would at least be a good stepping stone toward a gigantic collab film featuring heroes who’d just had their own films. Instead Hulk was a financial bomb and Iron Man was a meteoric success. I don’t need to give you a blow by blow about how Marvel took over cinema for the next decade or two but the secret face behind this incredible rollout (apart from the magnetic power of Robert Downey Jr) is Kevin Feige. He got a foot in the door in 2000 as an assistant producer on X-Men due to his familiarity with everything Marvel. He made an impression and was quickly hired as a producer and second in command. He noticed that the aforementioned unclaimed “b graders” were all core members of The Avengers, and brainstormed the idea of a shared crossover film. He became the President of Production in 2007 and then promoted to president of Marvel Studios after Iron Man’s massive success. Today he is considered the highest grossing producer of all time.

2009

New Zealand got a newly acquitted David Bane in 2009, kicking off a debate that continues to today. On January 3rd the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto kicked off Bitcoin starting a tech revolution that would snowball exponentially all the way to today. Swedish game developer Markus “Notch” Persson released a little game online called Minecraft. Windows, which would one day acquire this multigenerational game property released Windows 7. Finally we got our first good taste of a pandemic scare when Swine flu started sweeping around.

2Degrees

Formerly started in 2001 under the name NZ Communications 2 Degrees wouldn’t become what we know it as today until 2009 when it changed it’s name and announced a roaming deal with Vodafone. It’s easy to forget the bad old days of text charges. When 2degrees demolished the market Telecom and Vodafone were robbing us 20 cents a text uncontested. 2degrees brought this down to 9c a text with a bunch of free texts on top of that when people topped up. It was a game changer and competitive pricing brought down costs for kiwis across the board.

According to a 2018 report 2degrees has a mobile market share at 21%, with Vodafone at 41% and Spark at 32%.

Uber

Uber’s launch in 2009 was one of those rare occasions where our dreams of what an existing analog service could actually be with just a few modern digital tech improvements – came true. Exactly!

Waiting for a cab used to be a frustrating experience, where you had no idea where that ride you ordered was – or whether they were even going to turn up at all! Once you’d called it in, you just had to trust the operator would manage your cab ride through to your final destination. Otherwise you were powerless.

All that changed with Uber’s tech-driven, app-based model that prioritized speed, accessibility, and user experience. Brilliantly integrating GPS tracking and cashless payments, the app swiftly became a must-have – with the business Holy Grail of instant customer conversion becoming as simple as a single consumer trial.

But the real genius of Uber was the two-way rating system, which encouraged good service from drivers and reliability from customers – else they be punished with rejection next time around. A 21st century app encouraging social responsibility? Never!

Uber’s scalable platform, referral bonuses and surge pricing, set it apart making it a cultural phenomenon. Expansion was rapid worldwide and Uber adapted brilliantly to diverse markets: offering auto-rickshaws in India, motorbikes in Southeast Asia, and partnering with local payment systems. Despite competition from others like Lyft and Ola, Uber’s brand became synonymous with ride-sharing, turning ‘Uber it’ into a verb like Xerox and Hoover before.

By its 2019 IPO, Uber’s valuation had soared to $82 billion, reflecting its entrenched global presence. Beyond rides, Uber has diversified into food delivery with Uber Eats and freight logistics, cementing its role in urban mobility. Despite regulatory battles, its impact is undeniable: Uber didn’t just modernise transport—it has redefined how cities move, proving that technology and user-centric design could overhaul even the most entrenched industries. Uber also serves as a shot across the bows of Tradition – just because you’ve been doing it for ages, doesn’t mean we can do it a whole lot better from now on!

2010

The Pike River Mine accident was the biggest news of the year in New Zealand. Later 25 criminal charges would be filed in relation to the disaster.

Abroad 2010 marked the start of the Arab Spring. A wave of pro-democracy anti-corruption revolts spread across the Arab world. At home we were busy being stoked for our rugby team, which sounds a lot less important when framed with other world events. Either way Dan Carter was our man of the year and also became the highest point scorer of all time, tussling for the title against England’s Jonny Wilkinson. This year we were pretty proud of ourselves for finally making the jump to digital via this new fangled “Google Android”. The mobile operating system got off the ground in very late 2007 and it had hit a stage of maturity by the time we entered the market in 2010. This was the year Steve Jobs also announced the first iPad, which was a revolutionary new way for people to muck around online.

Apple

2010 was the magical year Apple gave us the iPad. As usual, Apple was ahead of the curve as I remember wondering why I needed this near monitor-sized screen on a tablet at the time. Oh ho ho! How silly that question seems now that broadcast TV has faded into obscurity – to be replaced by all forms of on-demand entertainment, for which the iPad seems the perfect vehicle today.

Apple told us back in 2010 that the iPad would be the new ‘third category’ of interface nestled in between the laptop and the smartphone. We didn’t believe them – until we tried editing videos on the couch or following a recipe in the kitchen, with no more keyboards or cables. Just sleek glass, easy-to-use apps and plenty of instant gratification.

Suddenly, laptops felt archaic and the iPad’s mobility mixed with its flexibility made it shorthand for ‘do anything, anywhere.’ It evolved too: Pro models wooed creatives, Minis charmed travelers, and accessories like the Apple Pencil turned doodlers into digital Picassos. By 2021, over 500 million iPads had sold, reshaping education, design, and even healthcare.

Another legacy of the iPad was its popularisation of the humble ‘app’. Sure, apps had been around for a while with the iPhone laying the groundwork back in 2007, but the iPad’s expansive screen and intuitive interface turned apps into immersive experiences. Suddenly, apps weren’t just for checking email or playing Angry Birds on a tiny display; they became tools for sketching, video editing, reading, teaching, and even piloting drones. The iPad’s larger canvas made apps feel indispensable, not just convenient. Not a bad legacy for a product that seemed surplus to requirements at the time of its launch!

Vend

Spun up in 2009 and launched in 2010 by Vaughan Fergusson Vend set out to give more flexible point of sale options to venders. Out with cash registers, in with iPads. It was immediately apparent that this was a hot idea, investors like Peter Thiel were quick to jump aboard. Today Vend has more than 25,000 retailers and generated US$34m in revenue in 2020. In 2024 the company was sold to American company Lightspeed for US$350 million.

This isn’t Vaughan Fergusson’s first big win by a long shot. He slipped into Vend right after selling travel booking company Vianet to Trademe in 2008. Trademe would rename it Travelbug.co.nz.

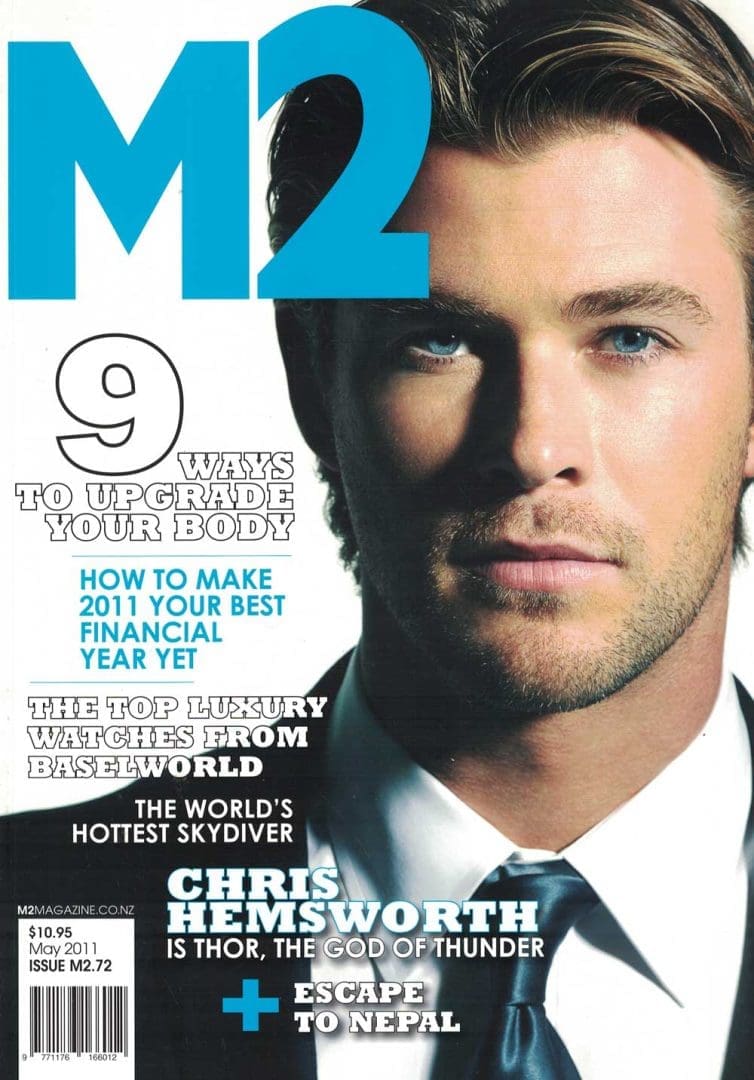

2011

Look at Chris Hemsworth! He looks like a baby! We lost C4 this year when it got rebranded to Four. Overall it was a dark year for New Zealand, especially for Christchurch in particular when the earthquakes took lives and ruined thousands of others. The scars of this event are still felt and seen to this day.

Garage Project

New Zealand went through an incredible boom of craft beers. You couldn’t swing a six pack without hitting a dude in the middle of describing how “hoppy” something tasted. In the midst of this boom there were bound to be winners and losers, the market can only get so saturated. One of the winners was Garage Project based out of Wellington. To get an idea of just how busy the market is in 2017 they won Brewer of the Year edging out 111 other breweries. That seems like a lot for such a little country but I guess we do know how to pack away a pint. After finding local success they have begun branching out overseas with distribution across the ditch in Australia, and further afield in Norway, Sweden, and California.

The Rugby World Cup

2011 was the year of Redemption. Finally the pain of 24 years was put to bed as the mighty New Zealand All Blacks at long last lived up to their promise and took out the big prize by winning the Rugby World Cup. Whew! Thank God!

Sure, we’d won it before in 1987 – but David Lange was Prime Minister and the Bangles were still walking like Egyptians way back then. Surely it was time to win it again? We’d had so many freakishly good players over those 24 years like Christian Cullen, Tana Umaga, Zinzan Brooke, Jeff Wilson and a certain chap called Jonah Lomu – yet we still couldn’t win it. Even with the sainted Richie McCaw and Dan Carter we’d failed yet again in ‘03 and ‘07.

But why? From 2004 to 2011 the All Blacks had pulverised everyone repeatedly. Then, not being content with unbeaten campaigns, they’d started handing out 50 point thrashings to really good international sides like the Springboks and Wallabies AWAY. Even the famous British and Irish Lions had skulked back home with their tails between their legs having been whipped mercilessly over three Tests in 2005.

Yet, come World Cup time, we’d turn into the equivalent of South Africa’s cricket Proteas who were the ultimate ‘chokers’. Despite an endless stream of quality teams stacked with unbelievable players – they had gone home empty-handed every time despite making SO many Finals and Semifinals.

The key turning point for the All Blacks, though insanely controversial at the time, was to reappoint Graham Henry et al as coaches after the ‘07 failure. This gave them a chance to learn from their mistakes rather than pass on the same old problems to a bunch of new guys. Add in the influence of mental skills coach Gilbert Enoka and his ‘walk toward the pressure’ philosophy helping to turn chokers into winners – and the All Blacks were finally able to lift the Cup at last. Just!

Of course, the All Blacks have had what can only be euphemistically described as ‘mixed’ results in recent years with no more World Cup triumphs since 2015 and regular disjointed performances. But we are chokers no more – and that’s the biggest victory of all.

2012

In 2012 Robert Downey Jr was hotter than hot coming off the back of two Ironman movies that would define the rest of his career for the next decade. To keep himself occupied he starred in the perfectly average Guy Ritchie Sherlock Holmes flick.

Xero Goes Global

While Boston Dynamics was rewriting our sci-fi nightmares, a Kiwi company was rewriting the rules of business in the cloud. Xero, founded in Wellington by Rod Drury in 2006, had reached a tipping point by 2012. It had grown from a bold local startup into a serious international contender, with expansions into Australia, the UK, and the US all in motion. Xero didn’t just digitise accounting, it made it user-friendly. It took the tedium out of the books and gave small businesses access to real-time insights and automated tasks previously reserved for companies with entire finance departments. By 2012, Xero had raised tens of millions in capital, listed on the NZX and ASX, and earned praise from tech circles overseas. It was quickly becoming one of the crown jewels of New Zealand’s tech ecosystem, a company that proved we could build global software brands without ever leaving our shores. And best of all, it still felt like ours.

Tinder

Swiping left or right for a partner, long term or otherwise, started in 2012 with the advent of Tinder. Sure, the idea of dating sites had already been around for a while with websites like OKCupid and Eharmony taking over from personal ads in the newspaper but the swiping was an all-new thing. It allowed us to quickly shuffle through a bunch of options like a deck of cards and it really caught on globally with Tinder recording over 70 million monthly active users worldwide and, more importantly, over 65 million matches as well. Those 5 million unmatched? Well, they’re obviously undateable! Tinder soon faced competition from many other dating sites, some of whom even copied their swiping feature like Bumble but Tinder has remained the

gold standard even to this day. Though online and app dating sites have attracted plenty of critics from across the spectrum, they have also allowed potential partners to actually pair up via shared interests rather than just bellow at each other over ridiculously loud music in pubs or clubs. And that has to be a swipe in the right direction!

20 years of Boston Dynamics

Boston Dynamics had been quietly redefining what robots could do since the 1990s, but by 2012 the internet had truly caught up. The company, originally spun out of MIT and fuelled by DARPA contracts, had developed a reputation for creating machines that looked more like creatures than code. BigDog could trudge through snow, climb rubble, and regain its balance when kicked, turning military contractors and YouTube viewers equally into fans. Their humanoid robot PETMAN walked, squatted and even simulated breathing, built to test protective clothing under realistic conditions. Then came Cheetah, setting records for speed. In 2012, these weren’t just prototypes, they were viral sensations. While the robots were still tethered to support rigs and external power sources, the writing was on the wall: Boston Dynamics was on a different trajectory from the rest of robotics. It was one of the first moments where the world looked at a robot and thought: “Whoa. That’s actually kind of scary.”

2013

Three years after we had entered the market on Android we also jumped onto the iPad, with our Jeff Ross issue being our first trial run at interactive magazines.

Jeff Ross had completely turned the alcohol business upside down with the introduction of his 42Below Vodka. He had started small working out of his own garage before growing the business to a point where Bacardi Ltd was interested enough in what he had built to make him worth 35 million. Overseas 42Below was a fashion piece. This made Ross our Lexus M2 Man of the Year in 2013.

CRISPR

While the biology behind CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats – yikes!) had been around for yonks, 2013 was the year it really transformed from lab plaything to real-world application.

How? First of all, scientists Doudna and Charpentier showed how to cut DNA precisely in a test tube, then Feng Yang’s team demonstrated how CRISPR editing could be done with human cells…

Woah! Say what? You mean CRISPR lets us edit DNA in living organisms, like correcting a typo in a Word file?

Oh yes, that is exactly what it meant. Cue a mad scramble worldwide to refine and adapt CRISPR for a variety of uses. Investors poured money into CRISPR startups, and corporate wars broke out over patents. The first CRISPR-based companies emerged like Editas Medicine and CRISPR Therapeutics aiming to turn the scientists’ lab discoveries into therapies. Already there has been some success with CRISPR-based treatments for sickle cell anemia and beta-thalassemia—painful, inherited blood disorders—coming out. Plus, there are also clinical trials currently operating exploring cures for genetic blindness, HIV, and cancer.

Meanwhile over in agriculture, giants like Bayer and Corteva began developing CRISPR-edited seeds as a faster, more precise alternative to older genetic modification methods. Crops have also been edited to withstand droughts, pests, and soup up nutrition like vitamin-enriched tomatoes. The biofuel and materials science industries also use CRISPR to engineer microbes for eco-friendly products.

Looking ahead, there seems to be no limit to what CRISPR can do in future. It’s capable of creating one-time cures for diseases like cystic fibrosis as well as being personalised to our own DNA to create tailored medicine for treating our own unique ailments. CRISPR can adjust crops to make them more resistant to climate extremes and may even be able to gene-edit pests like mosquitoes.

Used correctly going forward, CRISPR could be the biggest success humankind has seen since the invention of the computer – if not the wheel.

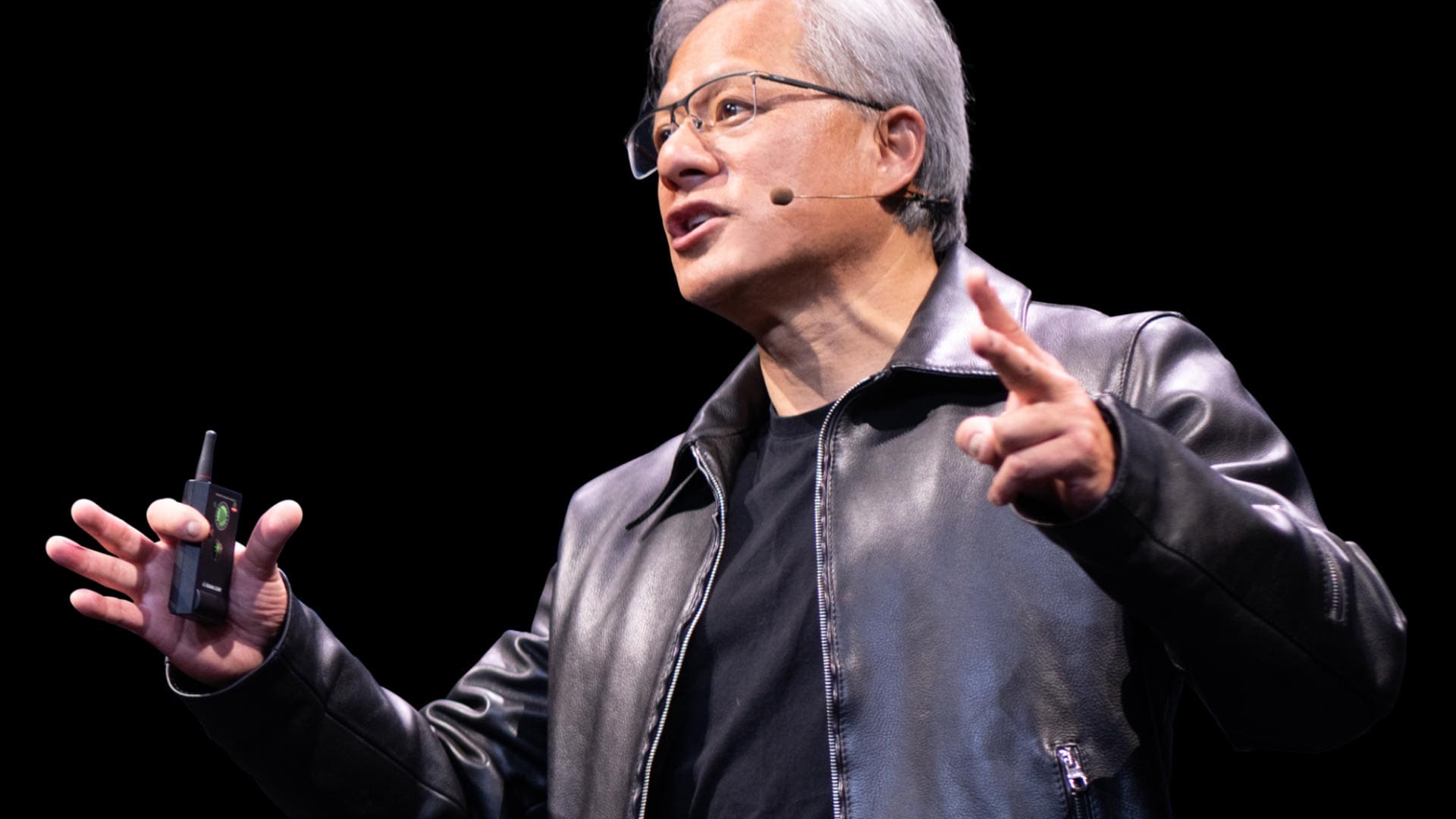

20 years of Nvidia

Got it’s start in 1993 when Jensen Huang, Chris Malachowsky, and Curtis Priem had a little dream to bring accelerated graphics potential to PCs. By 1999 they had made what they marketed as “the world’s first GPU”, the GeForce 256. It’s a wee bit cheeky considering that Sony had coined the term in 1994 with the Playstation’s chip, but Nvidia managed to make it go mainstream. The GeForce 256 actually did all the graphics processing, rather than just being a passthrough card like the Monster 3D which still relied on your CPU to do the heavy lifting.

These days Nvidia is making headlines as it stocks ride the wave of AI, and everyone’s desperate need for more grunt, whether it before for Large Language Models or bitcoin mining.

2014

20 years of DJI

In 2014, DJI stopped being a niche name among hobbyists and became a three-letter acronym for the drone revolution. Up until this point, aerial photography usually involved hiring a helicopter, a gimbal, and a solid tolerance for nausea. But DJI’s Phantom 2 changed all that. It was sleek, stabilised, and user-friendly enough that even your cousin Dave could send one up at Christmas and wipe it out on the neighbour’s gazebo.

What really set DJI apart in 2014 was the introduction of their first integrated camera drone, the Inspire 1. It looked like a sci-fi insect and gave filmmakers, surveyors, and weekend enthusiasts access to aerial footage that would’ve cost thousands just a year earlier. It was the moment drones went from toys to tools.

Suddenly, everyone from real estate agents to indie directors to farmers wanted a bird’s-eye view. DJI didn’t invent the drone, but they made it fly off shelves and into regulatory grey areas worldwide.

Vista Group IPO

If you’ve ever bought a cinema ticket online, ordered popcorn through an app, or sat in a seat that somehow knew your name, chances are Vista Group was behind it. While the world in 2014 was obsessing over wearable tech and chat apps, a little software company from Auckland was quietly running the back end of the global film industry. That year, Vista Group listed on the NZX and ASX in a move that solidified their ambition of building an empire behind the screen.

Vista’s tech powered everything from box office sales to loyalty programmes to analytics dashboards for cinema operators in over 60 countries. The kind of digital infrastructure that made the cinema-going experience feel seamless while studios and exhibitors tried to figure out how to stay relevant in the Netflix age.

The IPO in 2014 gave the company fresh capital, fresh headlines, and a new layer of credibility. It also marked a rare feat: a New Zealand tech company that had gone global without losing its grip on its niche. Vista wasn’t trying to be everything to everyone. It was just trying to make the film industry smarter and it was doing a bloody good job of it.

20 years of Amazon

By 2014, Amazon had well and truly outgrown the ‘online bookshop’ label. At this point, it was less “e-commerce platform” and more “borderline utility company.” If you were buying things, streaming things, running a website, or reading on anything that wasn’t made from dead trees, chances are Amazon was involved. Jeff Bezos, who once looked like someone’s friendly accounting teacher, now bore a closer resemblance to a Bond villain with an aerospace hobby and a trillion-dollar runway.

While other companies were still getting their heads around ‘digital transformation,’ Amazon had quietly built AWS, the cloud computing giant no one saw coming. It powered everything from your local startup to global banks and probably a fair chunk of your personal procrastination apps. Meanwhile, Amazon Prime was rewiring consumer expectations, turning overnight delivery into a moral right and binge-watching into a lifestyle. The company had its fingers in retail, logistics, entertainment, publishing, AI, and the growing belief that one day it might ship you a vacuum cleaner before you even knew you needed it. And all of this, somehow, with a website that still looked like it hadn’t been updated since 2003.

Amazon in 2014 wasn’t just a tech company. It was infrastructure. An empire. The place where innovation met ruthless efficiency.

2015

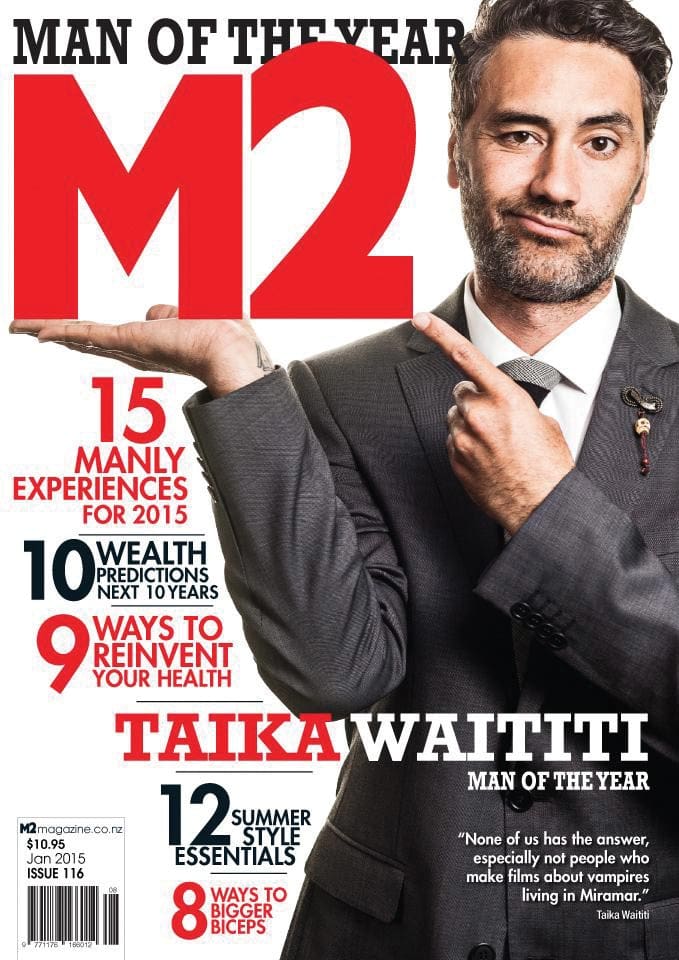

Issue 116 was to be the first of many times Taika Waititi would grace the cover of our magazine, shooting right to the top as Man of the Year. The now legendary director was hot off the back of the mocumentary, What We Do In The Shadows for this issue. The movie would go on to spawn multiple critically acclaimed TV shows. He already had Eagle Vs Shark and Boy under his belt at this point and we could see this guy going places. We had no idea quite how right we would be.

20 years of Ebay

One of the original dot-com darlings, eBay turned 20 in 2015, and like many 20-year-olds, it was going through a bit of an identity crisis. It was no longer the scrappy disruptor that let you auction off your Beanie Babies and broken Tamagotchis to strangers across the globe. But it hadn’t quite evolved into the slick e-commerce machine that modern consumers now expected.

Still, eBay had staying power. It had weathered the rise of Amazon, the fall of Yahoo, and more questionable PayPal passwords than most platforms would survive. It was still the go-to for niche collectors, small business sellers, and anyone who wanted to feel the primal thrill of a last-second bidding war. In a world obsessed with frictionless one-click shopping, eBay offered something messier, more human—and weirdly, more fun.

In 2015, the company spun off PayPal in a high-profile divorce that left both parties a little leaner and supposedly more focused. For eBay, it was a chance to find its second wind. Not by becoming the next Amazon, but by embracing what it always did best: connecting people who have stuff with people who want that stuff. Preferably with a countdown timer and a sense of nostalgia.

Apple Watch

By 2015, Apple had already conquered your desk, your pocket, and possibly your lounge — so the next logical step? Your wrist. The launch of the Apple Watch marked the company’s first new product category since the iPad, and while reactions ranged from “game-changer” to “expensive step counter,” it was a bold move into wearables from a company that had a history of turning accessories into cultural artefacts.

While Gen 1 was arguably a bit sluggish and undercooked it laid the groundwork for what would become the world’s most popular watch, not just smartwatch, but watch full stop. No longer niche. No longer just for runners. The Apple Watch brought fitness, notifications, payments and mild panic (thanks, heart rate alerts) right to your wrist.

Paris Climate Agreement

2015 was the year of the Paris Climate Agreement. Ratified by 195 countries(!), it is a landmark global effort to combat climate change. Its primary goal is to limit global warming to “well below 2°C” above pre-industrial levels, with an aspirational target of 1.5°C.

The Agreement has achieved massive success by getting both developed and developing countries to commit to climate action. These countries all submitted Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—voluntary pledges to reduce emissions—and these plans have driven a host of domestic policy shifts, renewable energy investments, and corporate sustainability initiatives. Renewable energy adoption has also surged globally, with solar and wind power costs dropping by over 80% and 60%, respectively. The agreement has also normalised climate accountability, inspiring mid-century net-zero pledges from major players like the EU, China and the U.S.

Sure, the Paris Climate Agreement has a hard row to hoe getting the world to clean up all its pollutants but its biggest success – the U.S.’s Big Energy propaganda apart – has been to normalise the concept of climate change action globally. With almost everyone on the same page worldwide this should create enough momentum to see some real valuable change over time.

2016

Sharesies

Launched in Wellington in 2016, Sharesies had a radicacal idea: what if anyone could buy shares, not just the guys in suits who used words like “portfolio” and “bull run”? No minimums. No brokers. No condescension. Just a slick, friendly app and a low-stakes way to dip your toes in the market. You could invest $5 and could channel your inner Warren Buffett.

By stripping out the jargon and dropping the intimidation factor, Sharesies opened the NZX and global markets to thousands of first-time investors, many of them young and many who’d never considered finance their thing. The impact was huge. Suddenly, investing wasn’t just for the financially fluent it was for everyone with a smartphone and a bit of curiosity.

Donald Trump

Unless you were marooned on a desert island all year without a satellite phone, you would have to agree 2016 was the year of Donald Trump.

Loathe or hate him, he was impossible to ignore with his lowbrow insults and vivid pandering to the fascist tendencies of his audience, reducing the Republican Primary and later U.S. Presidential Election down to the level of WWE ringside promos. Still, he’d stumbled into rich territory serving as an antidote to the pretentious Ivory Tower proselytising of out-of-touch Democrats like Elizabeth Warren and Hillary Clinton. The Democrats dutifully handed him the Presidency on a plate by persisting with Clinton over Bernie Sanders who had the youth and a decent chunk of working class sewn up. Little wonder then that Trump triumphed as his campaign manager Kellyanne ‘Alternative Facts’ Conway noted that Hillary was the ‘one of the least motivating speakers in modern political history’. A stark contrast to Trump who was able to energise massive crowds with his populist nonsense.

Now of course, he’s back and more experienced if not wiser. But he is arguably exactly what America needs as his recent meddling in the U.S. economy shows. Trump’s attempt to force interest rates down so the U.S. can refinance debt is a bold plan. Far more ballsy a course of action than any other Administration would ever consider. Unfortunately for Trump, his narcissistic personality, rampant inferiority complex and low IQ would only ever allow an echo chamber of sycophants around him. That means there’s no one around to point out when an idea is so dumb it’s guaranteed to blow up in his face.

For example; Trump’s switching sides on Ukraine has dealt a potentially mortal blow to the U.S. military-industrial complex – still a key pillar of its economy. Already nations are lining up to switch away from American arms dealers as they have no confidence in any future alliance with the U.S.

It is this determination to press on with bad policy rather than admit his own errors will see Trump succeed with his ultimate goal of destroying the very country he purports to love.

Oculus Rift

After decades of cinematic hype, academic theory, and gaming forums arguing about frame rates, virtual reality finally arrived in our actual reality. In 2016, Oculus Rift launched its first consumer-ready headset, a chunky, goggled piece of hardware that let you step inside digital worlds for the first time without needing a university research grant or a bucket for motion sickness.

This was Facebook’s bold new frontier. Mark Zuckerberg had dropped US$2 billion on Oculus back in 2014 and was already preaching the gospel of “presence,” the idea that in the not-so-distant future, we’d all be working and socialising in the metaverse instead of boring old real life. Oculus was the gateway drug: strap in, download a few demos, and suddenly you’re in space, swinging lightsabers or painting in thin air.

And to be fair, it kind of worked. Gamers loved it. Developers loved it. People at TED talks really loved it. The Oculus Rift wasn’t exactly sleek but it was the first real taste of something big.

Fast forward a few years, though, and the road to virtual utopia has been… bumpy. Facebook rebranded as Meta, poured billions into building out a metaverse full of legless avatars and empty digital plazas, and mostly got roasted by the internet. Turns out people didn’t want to live in a headset full-time, especially if it meant attending virtual meetings in a pixelated beige office with strangers named CryptoDad42.

Still, 2016 was the moment the headset wars truly began. Oculus kicked the door open, and while the metaverse hasn’t exactly taken over daily life (yet), it did lay the foundation for what’s next in gaming, in entertainment, and in whatever mixed-reality thing Apple’s cooking up. It might not have changed everything straight away… but it definitely changed the conversation.

2017

We always like to celebrate excellence in the field, whether it’s in the director’s chair or in the boardroom. In Peter Burling’s case it was excellence in the ocean when he became the youngest winning helmsman in the history of the America’s Cup. He brought home the cup for the 35th America’s cup alongside the rest of the crew and engineers behind Emirates Team New Zealand.

Hnry

Launched in 2017 from the startup petri dish of Wellington, Hnry arrived with a bold pitch: what if freelancers didn’t have to deal with tax ever again? No spreadsheets. No invoices floating around your inbox. No panicked emails to your accountant on 31 March. Just click a few buttons, get paid, and boom taxes, ACC, GST, and student loan repayments all sorted behind the scenes like magic (or, more accurately, software).

For years, the self-employed had been treated like second-class citizens in the financial world left to DIY their way through compliance with an Excel sheet and a gut feeling. Hnry flipped that script. It became your accountant, your tax agent, your invoicing system and your financial safety net all rolled into one.

By targeting the growing army of contractors, freelancers, gig workers and one-man-bands, Hnry tapped into a demographic that had been growing fast but largely ignored by banks and accounting firms. And they did it with the kind of branding that actually sounded like a human being was behind it.

Slack The Unicorn

Once upon a time, work chats meant actually talking to your work colleagues in person. How antiquated. Then along came Slack, and by 2017, office communication had morphed into something more like a never-ending online group chat, complete with breakaway channels, but still that one overzealous colleague who kept trying to “@channel” the whole team during lunch.

Slack wasn’t brand new by 2017, but this was the year it truly hit its stride. It was adding users by the million, raising capital by the bucketload and hitting unicorn status. Suddenly, “Let’s Slack about it” replaced “Let’s meet,” and most of us discovered we could communicate entirely through emojis, passive-aggressive thread replies, and reaction gifs.

Slack also helped to level out the workplace. Interns could message the CEO. Developers could talk directly to designers. And everyone had a say in naming the #banter channel.

But little did the world know at the time, Slack was primed for something bigger. Just a few years later, when COVID-19 turned kitchen tables into office desks and every conversation had to happen through a screen, Slack became the glue that held entire companies together. While managers scrambled, servers strained, and webcams revealed a bit too much at times, Slack kept teams talking, laughing, venting, and hitting deadlines across time zones.

20 years of Netflix

Back in 1997, Netflix was just an upstart DVD rental service trying to put Blockbuster out of business one envelope at a time. Fast forward 20 years, and Blockbuster is a trivia question and Netflix is the empire that rewired the way we consume culture. By 2017, it had transformed from scrappy disruptor to the studio, the network, and the distributor rolled into one.

It wasn’t just showing other people’s stuff anymore, it was pumping out original content like an unstoppable entertainment factory. This was the year The Crown took home golden statues, 13 Reasons Why had schools in a panic, and Stranger Things turned a Dungeons & Dragons reference into a global phenomenon. “Netflix Original” had become a genre in itself, with budgets that rivalled Hollywood blockbusters.

More than that, Netflix taught us new behaviours. It killed off the concept of ‘waiting a week’ for the next episode and replaced it with the now-sacred binge. It rewired sleep patterns, ruined productivity, and made “Are you still watching?” feel like a personal attack. It knew your guilty pleasures better than your partner did and wasn’t afraid to recommend another true crime doco at 2am.

By 2017, Netflix had also gone global, expanding to over 190 countries. It had sparked the streaming wars, redefined data-driven content production, and turned the humble algorithm into a tastemaker.

2018

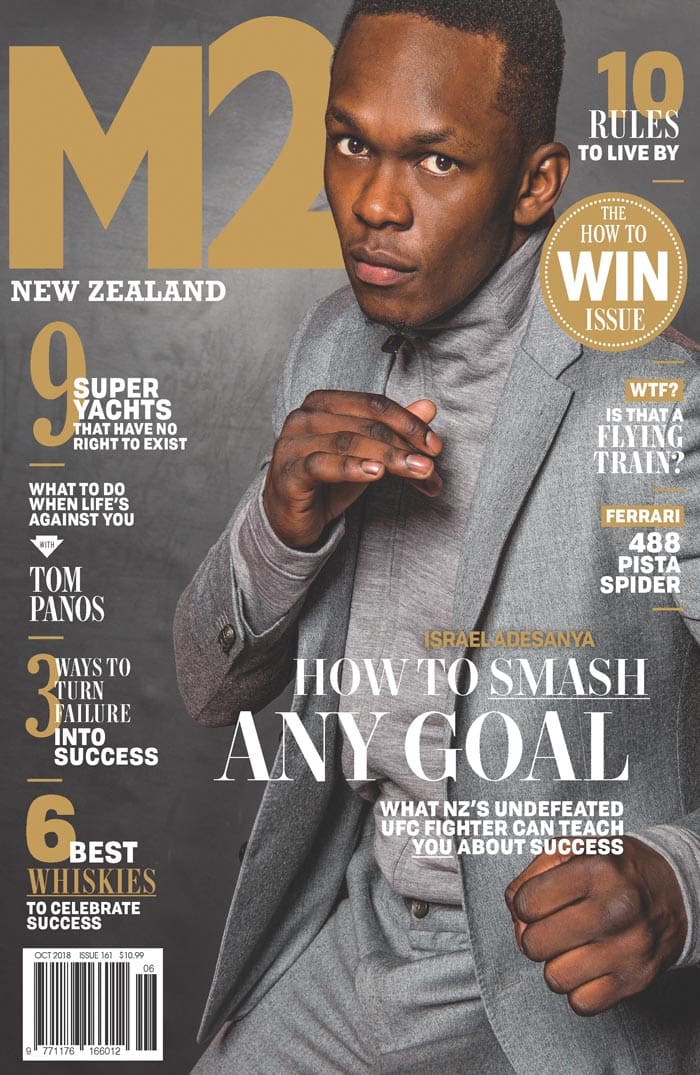

We got to hang out with Israel Adesanya for a day of photoshoots and interviews. This man is a loose cannon and gets himself in hot water a lot with his public comments, but you know what, that’s just the sort of person who gets TKOs in the ring. During the photoshoot we were also using it as a chance to do a style shoot. Our editor was terrified during the butterfly kick shots that we’d be returning the clothes with a split crotch, but they held up admirably. No loose tackle during the shoot. This time.

TikTok

In 2018, most people over 30 had no idea what TikTok was, and those under 20 were already spending six hours a day on it. What started as a quirky Chinese lip-sync app (Musical.ly) quietly merged with a short-form video platform called Douyin, and just like that, TikTok was born. No press release. No dramatic launch. Just an app that would quietly go on to hijack global attention spans.

At first, it looked like digital karaoke for teens. But behind the goofy filters and 15-second dances was something much more potent: an algorithm so sharp, so hypnotically tailored, it knew what you liked before you did. TikTok didn’t care who you followed, it just fed you content. One scroll, one dopamine hit at a time.

By the end of 2018, it had already passed 500 million global users, outpacing Twitter and Snapchat, and it was still considered “niche.” But the early signs were there: dance trends going global overnight, teenagers becoming full-time influencers, and a sense that the cultural centre of gravity was quietly shifting to vertical video.

TikTok was a vibe shift as the kids say these days. Content got shorter. Edits got sharper. Everyone suddenly wanted to be a creator. And attention spans? Well… hey, are you still reading this?

20 years of Google

In 1998, two PhD students working out of a garage thought they’d build a better search engine. Twenty years later, Google wasn’t just helping people find things it was shaping what they found, what they saw, and increasingly, what they believed. By 2018, it had gone from noun to verb to near-utility status. You didn’t “look it up” anymore you Googled it.

In those two decades, Google had expanded from search into… well, everything. It ran your email, your maps, your calendar, your documents, your storage, your browser and maybe even your phone’s operating system. It was the homepage of the internet and, depending on your perspective, the benevolent librarian or the slightly invasive landlord.

2018 marked a moment of reflection for the tech titan. It had long since dropped its “Don’t be evil” motto from the company code, and now people were starting to ask uncomfortable questions. Should one company really control this much information? Was the algorithm fair? Was it too good at knowing what we wanted?

Still, despite growing scrutiny, Google in 2018 was inescapable. Android was running on over two billion devices. Chrome was the world’s most popular browser. YouTube (which it acquired back in 2006) had become the go-to platform for education, distraction, and conspiracy theory rabbit holes. Google Assistant was in your pocket and your home, learning how you spoke so it could better interrupt you mid-conversation.

Google had become the default answer to almost every question — even the ones about whether Google had too many answers.

GPT-2

In 2018, OpenAI quietly built something that both thrilled and slightly terrified the tech world: a text-generating AI model called GPT-2. It could write essays, answer questions, summarise articles, mimic Shakespeare, generate fake news, and go completely off the rails.

OpenAI’s researchers were so spooked by its potential misuse that they initially refused to release the full model. That move created an instant buzz. Everyone wanted to know: could this thing really write like a human? And if so… whose job was next?

GPT-2 wasn’t perfect. It hallucinated facts and got distracted mid-thought but what it showed was clear: language itself was now programmable. And little did we know, this was just the warm-up act. A few years later, its successor GPT-3 would write code, poems, love letters, and startup pitches. By then, AI wasn’t just automating jobs. It was coming for creativity.

2019

Peter Beck is THE face of New Zealand’s space initiatives, putting our little country on the map on the road to the stars. We were so impressed with what he’s been able to achieve since starting the company that we named him Man of the Year twice in a row in both 2018 and 2019. Rocket Lab was founded in 2006, and by 2009 had become the first ever private company in the southern hemisphere to reach space.

Along the way it hasn’t been without its controversies but the impact of the company has been undeniable. In 2018 they conducted their first mission for NASA and they also began to develop reusable first-stage tech.

Amusingly in 2018 we also played into how bad the year was for everyone. Little did we know 2020 was just around the corner.

20 years of Alibaba

In 1999, Jack Ma launched Alibaba out of his apartment in Hangzhou with a dream, a dial-up connection, and zero knowledge of coding. Twenty years later, Alibaba wasn’t just the Amazon of China, it was China’s digital economy in one sprawling, hyper-efficient, AI-fuelled ecosystem. By 2019, Alibaba had its hands in e-commerce, cloud computing, logistics, fintech, entertainment, and more, all scaled to a level that made most Western CEOs either envious or quietly anxious.

While Amazon grew by perfecting logistics, Alibaba grew by building platforms. It didn’t own the inventory, it just connected millions of buyers and sellers and then monetised everything around that transaction. Want to sell sunglasses from Guangzhou to someone in Ghana? Done. Need cloud storage? Use Alibaba Cloud. Want to stream a movie, order lunch, or get a small business loan with a few taps? Jack Ma’s empire had you covered.

In 2019, Alibaba celebrated its 20th anniversary with a bang. It set yet another Singles’ Day sales record, raking in US$38.4 billion in 24 hours, more than Black Friday and Cyber Monday combined.

But the real story was how Alibaba had woven itself into the fabric of everyday life in China. Taobao was where you shopped. Alipay was how you paid. Cainiao delivered it. And Ant Financial was your digital wallet.

The IPO of Alibaba’s fintech arm, Ant Group, was still just over the horizon (and would eventually be torpedoed), but in 2019, Alibaba was riding high.

Disney+

By 2019, Disney had been pumping out content for nearly a century… but streaming? That was someone else’s game. Netflix had already rewritten how we watched TV. Amazon was in the ring. HBO was circling. But when it launched in November 2019, Disney+ wasn’t just another subscription service, it was a streaming war nuke armed with decades of content, precision timing, and some of the most beloved IP on the planet. Marvel. Star Wars. Pixar. The entire back catalogue of Disney classics. And even The Simpsons, just to make it complete.

And it worked. Within 24 hours, Disney+ had over 10 million subscribers. And over 50 million within 6 months. Netflix had spent years building a subscriber base that Disney caught up with in a single fiscal quarter.

The launch wasn’t just about nostalgia. Disney+ arrived with The Mandalorian, a space western no one asked for but everyone immediately loved mostly thanks to Baby Yoda.

More than anything, Disney+ proved that owning your content and knowing how to monetise it across decades still mattered. In an age of algorithm-driven originals and hyper-personalised feeds, Disney bet on legacy, libraries, and fans who wanted to rewatch The Lion King with their kids and then watch Avengers: Endgame after bedtime.

2020

Our Beauden Barrett issue was midway through the pandemic and had cover lines like “How to Manage Stress in 2020”, “Lessons In Resilience” and “Continuing Business Through a Pandemic”.

It was a stressful time for everyone, and many of our competitors didn’t make it to the other side. We had done our first live Success Summit in 2019 and we were keen to get back into it, but in-person meetings were proving to be out of vogue this year.

One of the crew here at M2 optimistically said “the pandemic will be over in a few months eh.”

The rest of us were ready with buckets of water.

“It’ll take years.”

20 years of Baidu

Back in 2000, when most of the Western world was still figuring out how to make websites that loaded without crashing Netscape, a new search engine quietly launched in Beijing. Two decades later, Baidu. was no longer just “China’s Google” it was the company that effectively mapped, indexed, and monetised the world behind the Great Firewall.

By 2020, Baidu was a cornerstone of China’s digital ecosystem. Search, maps, news, cloud, AI it had fingers in all of it. It powered how over a billion people searched for everything from dumpling recipes to government policy. And while Google packed up and left the Chinese market back in 2010, Baidu stayed, scaled, and dominated.

The company had long since diversified beyond search. In 2020, it was going deep into autonomous vehicles, AI-driven healthcare, and cloud infrastructure not to mention competing with Alibaba and Tencent in everything from voice assistants to streaming. Its Apollo self-driving platform had backing from auto giants. Its DuerOS smart speaker was chatting away in Chinese households.

Of course, Baidu’s ride hasn’t always been smooth. Accusations of ad misplacement, concerns around censorship, and growing competition from ByteDance and others meant the company had to constantly reinvent itself. But 20 years in, it remained one of the most important and uniquely positioned tech players in the world.

Kami Goes Global

When classrooms around the world suddenly went dark in early 2020, most schools scrambled to figure out how to “go digital” with all the urgency of someone Googling “how to share 25 Mb PDF.” Enter Kami, a New Zealand startup that had quietly been building a simple but powerful solution for years: a digital classroom tool that let you annotate, collaborate, and mark up documents as if the classroom whiteboard had grown up and moved online.

Founded in Auckland in 2013 by a group of uni students who hated printing lecture notes, Kami wasn’t built for pandemics. But when one arrived, the company scaled with breathtaking speed. Its user base exploded from a few million to 25 million users globally by the end of 2020. American schools in particular adopted it en masse and in doing so, made Kami one of the most widely-used edtech platforms in the world… all from a little startup on the North Shore.

The magic of Kami was its simplicity. Teachers could annotate PDFs, students could write answers directly on-screen, and everyone could pretend even just a little that things were still somewhat normal.

Airbnb IPO

In early 2020, Airbnb looked like it might not make it to the end of the year. Borders were shutting, cities were locking down, and travel, the very foundation of Airbnb’s existence, had disappeared overnight. Within weeks, revenue plummeted by 80%. Hosts panicked. Guests cancelled. And suddenly, the most disruptive hospitality company in history was in survival mode. But Airbnb did something remarkable: it pivoted. Fast.

The company slashed costs, froze hiring, and pulled back its sprawling ambitions. It focused on core listings, community, and, crucially, domestic travel. As people around the world went stir-crazy in lockdowns, Airbnb offered something suddenly priceless: socially distant escapes. Cabins. Treehouses. Off-grid hideaways. You couldn’t fly to Rome, but you could rent a yurt an hour out of town.

By the time December rolled around, Airbnb had not only recovered, it pulled off one of the most stunning IPOs of the decade. Priced at US$68 a share, it popped to over $140 on day one, giving the company a US$100+ billion valuation. In a year where most travel brands were begging for bailouts, Airbnb was blitzing it.

2021

In 2021 we turned 16 in the middle of Covid weirdness but by this point the country had settled into a rhythm of knowing how to use Slack and Zoom, and the magazine was smoothly getting made remotely from home every time we were shepherded back there after an outbreak.

Throughout all this there were entrepreneurs doing amazing things even during an uphill battle. Tim Brown from Allbirds is a great example of kiwi ingenuity, taking renewable materials and making them into something great. In this case a pair of wool runners alongside Joey Zwillinger, the brains. It’s become such an iconic product that in 2018 Jacinda Ardern gifted a pair to Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull when he was in power for what felt like 3 seconds.

Partly

In 2021, while a big chunk of the startup world was busy flogging NFTs or pivoting to “Web3,” a group of engineers in Christchurch was quietly tackling one of the world’s most gloriously un Silicon Valley problems: auto parts.

Partly started with a mission to sort out the global car parts industry, which, as it turns out, is held together by duct tape, spreadsheets, and a disturbing number of faxes. Every year, billions of dollars in parts are bought and sold online and most of them are catalogued in wildly incompatible systems with vague names like “rear connector fitting B.”

Partly’s solution was to build the global infrastructure to power accurate, structured, searchable parts data and let any online store tap into it. Simple idea. Monumentally complex execution. But in 2021, they raised a strong seed round, built out their global vehicle database, and quietly started onboarding customers around the world.

Sure, it wasn’t sexy. It didn’t trend on Twitter. But it was smart, scalable, and solving a real problem that nobody else had managed to tame. By the time you realised you’d heard of them, Partly was already in the engine room of some of the world’s largest marketplaces.

Meta

With an awkward keynote, a floating VR avatar, and more hand gestures than a TED Talk, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook was now Meta — not just a new name, but a bold new mission: to build the metaverse. A fully immersive, persistent digital world where you could work, play, socialise, shop, and presumably still ignore your family’s group chat.

The timing was… convenient. Facebook had just come off a bruising year of whistleblower leaks, public hearings, and mounting concern that its platforms were fuelling misinformation, polarisation, and adolescent angst. So instead of fixing the timeline, Zuck decided to build an entirely new one. In 3D.

The metaverse pitch was massive: AR glasses, digital offices, floating homes, legless avatars, crypto economies, the whole Ready Player One fantasy, minus the cool soundtrack. Critics called it a distraction. Investors called it ambitious. Twitter called it “The Sims for sociopaths.” And yet, behind the noise, a real shift was happening.

Billions were poured into Reality Labs, the division behind Oculus (rebranded as Meta Quest), and Meta began hiring tens of thousands of developers to build its new digital empire. Whether it was visionary or vaporware was up for debate but it was undeniably bold.

Twenty Years of Fonterra

Starting in 2001 Fonterra has quickly made itself a cornerstone of New Zealand’s economy by being well, the biggest in the southern hemisphere. It’s revenues exceed $22 billion. The dairy co-operative has it’s roots stretching back to Otago in 1871 but a trend of consolidation after World War 2 led to just four major co-ops by the end of the 1990s. Fonterra came about after two of the largest, New Zealand Dairy Group and Kiwi Co-operative Dairies, merged. Combined Fonterra now commands around 30% of the world’s dairy exports. If Ukraine was the world’s bread basket New Zealand is the world’s opaque milk bottle.

They’re also pushing the R&D side of things to new levels. The Fonterra Research and Development Centre (FRDC) was responsible for the first whole genome to be sequenced in New Zealand when it mapped the genome of bacteriophage c2 in 1992 when it ran under the name of the New Zealand Dairy Research Institute (NZDRI). Today it holds over 350 milk related patents and is considered one of the largest dairy research centres in the world.

2022

2022 was tumultuous to say the least. The Ukraine war began in earnest after simmering for the better part of a decade in Crimea. The freedom camper anti-mandate protests broke out in front of the beehive, grinding a corner of Wellington to a halt. We lost the queen (she’s around here somewhere) and the Nord Stream pipeline blew up. Coincidence? We think not. The Queen has a lot to answer for.

Dawn Aerospace

While the rest of the world’s space race seemed locked in a contest to see who could make the biggest fireball, a team in Christchurch was taking a different approach altogether. Dawn Aerospace wasn’t building rockets to be launched once and retired. They were building spacecraft that could take off from a runway, fly to space, and be back in time for lunch.

In 2022, Dawn’s Mk-II Aurora, a sleek suborbital spaceplane designed for multiple flights a day, completed key test runs from a South Island airfield. Dawn’s in-space propulsion units, running on non-toxic propellants, were already guiding satellites into position around Earth. These weren’t experimental prototypes. They were commercial systems, designed to work quietly and reliably in orbit and they were being adopted by aerospace companies around the globe.

Musk X Twitter

In 2022, Elon Musk bought Twitter for US$44 billion, and somehow, that wasn’t even the strangest part of the story.

What started as a late-night tweet (“I might buy Twitter”) turned into a hostile takeover, legal wranglings and then once it was too late to back out an actual acquisition. The world’s richest man walked into Twitter HQ carrying a sink, fired the CEO, cleared out top execs, and promptly began reshaping the platform.

Musk renamed himself Chief Twit, gutted moderation teams, opened the floodgates for previously banned accounts, and changed the iconic blue check from a badge of identity to a US$8 subscription. Bots thrived. Advertisers bailed. Verified impersonators ran wild. Internally, Twitter became a warzone of overnight emails, new policies, and impromptu memos sent at 2am.

Then came the rebrand. Goodbye Twitter. Hello X, the long-promised “everything app” that Elon had been teasing since his PayPal days. No one really knew what that meant, but the blue bird was dead, and Musk’s vision was very much alive.

ChatGPT

On 30 November 2022, OpenAI quietly released a chatbot called ChatGPT. No splashy launch, no keynote, no celebrity endorsement. Just a web page, a text box, and the invitation to “ask me anything.” Within hours, people were typing in questions, prompts, essay topics, business ideas, bedtime stories, break-up texts and existential riddles and getting surprisingly coherent responses.

It wasn’t the first AI model to string a sentence together, but it was the first to make it feel accessible. Within five days, ChatGPT hit one million users. By January, it had over 100 million, making it the fastest-growing consumer product in internet history. Twitter flooded with screenshots of prompts ranging from “write a resignation letter as Batman” to “explain inflation like I’m five.” And for once, it felt like the internet had found a new toy everyone was playing with.

But beneath the novelty was something deeper: a new interface for knowledge, creativity, and productivity. ChatGPT could write code, draft reports, explain your toddler’s tantrum, or summarise Tolstoy. It also kicked off an AI arms race.

For OpenAI, it was a validation of years of work with the GPT-3.5 language model. For Microsoft, it was a reason to pour billions into integrating AI into everything from Word to Bing. And for Google? It was a very bad Monday.

2023

We’re skipping 2022 because the only thing interesting that happened was the nuclear clock ticking a couple seconds closer to midnight when Russia tried an all out assault into Ukraine. 2023 didn’t improve much when things kicked off between Israel and the Gaza Strip. In other news Labour’s term finished and Chris Luxon picked up the reigns while the two kids in the backseat, David Seymour and Winston Peters, fought over the toys.

Twenty Years of Zuru

The Mowbrays are everything you want in a success story. Starting as entrepreneurial kids selling hot air balloon model kits they briefly went to uni before deciding to go back to the thing that was actually working for them. One thing led to another and a 20k loan from Mum and Dad was enough to scrounge somewhat of a life in Hong Kong trying to hustle together a product. At their first trade fair they had an LED frisbee which was immediately taken off the shelf due to IP infringements they hadn’t heard about. But it was all part of the learning process. Later their showroom would double as sleeping quarters, Nick would hide his bed under the display table. With sheer hustle and no understanding of what they couldn’t do, they managed to innovate products and harass distributors with emails and phone calls till they made inroads. Today brothers Mat and Nick Mowbray are worth $20 billion, and in 2024 knocked Graeme Hart off the top spot for New Zealand’s richest man. Zuru’s Metal Machines now compete with Hot Wheels cars in my son’s toybox.

Runway

In 2023, a New York startup called Runway, caused more panic around Hollywood than a bad batch of Botox. With the launch of Gen-2, Runway introduced the world to the strange new reality of text-to-video. No stock footage. No camera gear. Just type in a phrase “a drone shot over a misty rainforest at sunrise” and the system would produce a fully formed video clip in a matter of seconds.

The technology wasn’t perfect, but that wasn’t really the point. It marked the moment where video became something that could be written, not just captured. And for a medium that has always required the most gear, people and budget to produce, that changed everything.

Suddenly, creative teams could generate concept footage instead of storyboards. Music videos could be visualised before a song was finished. Ads didn’t need a shoot, just a prompt and some editing. It didn’t make traditional video obsolete. But it offered a fast, flexible new layer on top.

Runway wasn’t alone in the space, but its mix of accessibility, design, and ambition gave it an edge.

2024

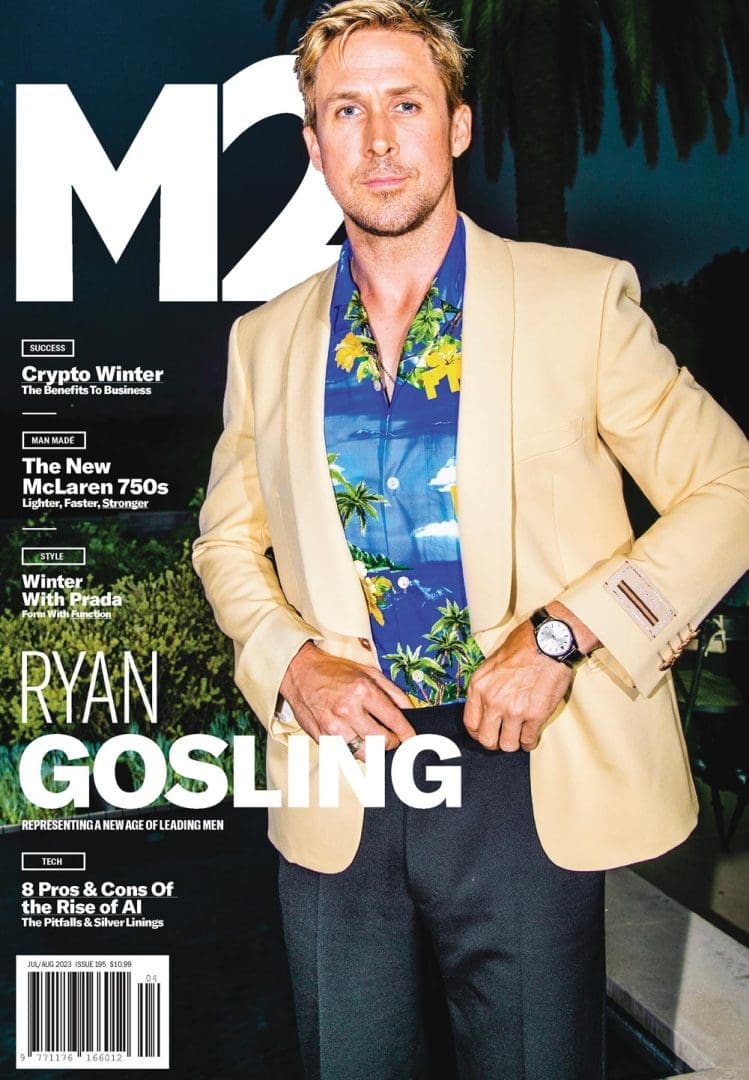

Anybody who’s anybody lives in 2024 right now. The magazine is now old enough to drink, so suffice to say our biggest mistakes and triumphs are lying ahead of us. Alongside our sister publication we have two live events running bringing together the best and brightest the country has to offer to discuss growth, success, and what the future might hold in store. At the moment the answer to that last one appears to be the use of the word “AI” a lot. Chat-GPT exploded the world a few years ago and it’s abilities have only grown since. We’re now living on the cusp of entirely generated video content. But I think no matter how far robots go, it’s still going to take the talent of someone like Waititi to wrangle it into a beautiful shape. Or someone as smart as any of the thought leaders we’ve talked to, to truly push the technology to its full potential.

Apple Vision Pro

When Apple finally revealed its long-rumoured headset in 2024, it wasn’t pitching entertainment or escapism it was selling the dream.

The Apple Vision Pro wasn’t a typical product launch. It was positioned as the beginning of a new platform, spatial computing, where apps and media floated in your physical space and the screen disappeared altogether.

The headset itself was technically impressive, dual 4K micro‑OLED displays, eye-tracking, hand control, spatial audio, and a build quality that made most other devices in the category feel like toys. But it also came with the usual early-adopter caveats: a two-hour battery pack, a NZ$6,000+ price tag, and a very real question about what it was actually for.

Apple didn’t talk about the metaverse. In fact, it barely acknowledged it. Instead, the Vision Pro focused on work, media, and extending your digital environment into the real one, watching a film on a virtual 50-metre screen, browsing your laptop in mid-air, revisiting old memories in spatial 3D.

For some, it was the start of something profound. For others, it felt like a beautifully designed solution still looking for a problem.

20 Years of Seequent

Founded in Christchurch in 2004, Seequent built a global reputation by making sense of what lies beneath the surface: geological structures, seismic shifts, mineral deposits, groundwater flows. The kind of data you don’t see, but that entire industries depend on.

At the heart of it all was Leapfrog, Seequent’s flagship 3D modelling software, which turned geological data into dynamic, interactive visualisations. What used to take months of manual interpretation could now be mapped, modelled and manipulated in a matter of hours. For mining companies, engineers, and environmental scientists, it changed the game bringing clarity to the most complex and opaque of systems.

By 2023, Seequent had grown from a quietly brilliant New Zealand success story into a global geoscience powerhouse. Acquired in 2021 by US engineering software giant Bentley Systems for over NZ$1 billion, Seequent retained its local roots while expanding its footprint across the Americas, Europe, and Asia. It wasn’t flashy tech, but it was foundational, the kind of deep-tech that underpins infrastructure, sustainability, and climate resilience projects all over the world.

2025

2025 has just got started but it’s already shaping up to be an interesting one. Europe is doing sweeping arrests of what they call far right politicians, disallowing them from running from election in an attempt to save democracy. Trump, at the time of writing is coming up hard to his own personal deadline for stitching up the Ukraine war, and as I sit here I’m discovering that New Zealand is considered on the same level as Costa Rica in terms of American Tariffs. Pretty much anything we write about 2025 at the moment is getting outdated within about 5 minutes of it happening. It’s an exciting year in the same way that streaking nude through a demolition derby is exciting.

Sora

When Runway introduced text-to-video a few years earlier, it as a true disrupter but when OpenAI released Sora in 2025, they took things to a whole other level. The platform generated full-minute, photorealistic video from text prompts, with smooth camera motion, realistic lighting, and a visual language that, while occasionally odd, was pretty cinematic.

What it offered was a working prototype of what the next generation of video might look like. Concept development, mood boards, proof-of-ideas, all rendered in motion, no actors or cameras needed. Production teams began using it to build storyboards that moved. Creators used it to visualise things they couldn’t otherwise afford to film. Marketers used it for campaigns that hadn’t been shot yet.

Runway opened the door. Sora walked through it with a tracking shot and a Michael Bay explosion in the background.

110 Years of Boeing

Boeing has been experiencing less than ideal headlines recently what with planes falling out of the sky, doors blowing off and just the odd whistleblower dropping dead here and there. But it’s hard to deny the impact the company has had on the art of flying and travel. Anyone who’s ever been anywhere has no doubt used one of Boeings planes to get there.

In 1914, William Boeing took his first flight with a Barnstormer and from there was hooked, making his own hanger later that year. By 1917 he was delivering his Model C’s to the Navy, marking the beginning of their relationship with the military industrial complex which continues to today. World War II popularised the B-17 Flying Fortress and B-52. Later the war would conclude when a B-29 bomber dropped nuclear payloads onto Japan, changing the world forever.

Later in 2011 the Japanese would use Boeing CH-47’s to drop sea water on the failing Fukushima Power Plant after the earthquake and tsunami almost led to a new nuclear disaster.

By revenue Boeing is the largest Aerospace company in the world, bringing in around $93.39 billion a year. Their ability to last throughout the decades isn’t just because they had an early lead on their competition, but also their ability to diversify. In the 70s they tried their hands with trains and These days they have contracts with NASA making the Boeing Starliner and various other satellite tech.

The 737 was first envisioned in 1964 and is still made in various forms to this day, making it the most popular commercial transport in the world. Production of the best selling 737-Max was stymied in 2024, but it’s hard to see Boeing getting knocked off its top perch anytime soon.

20XX

The year 20XX is a new golden age of Industrial economies as tech based economies collapse due to their ability to exist nowhere in particular. The largest company in the world is a multinational food production service run by a Proxy Bill Gates. Proxy, used sometimes as a slur, is a carefully maintained biological computer with silicon chips containing small amounts of a recently deceased person’s brain interfacing with an LLM. By now the public internet has ceased to be a functionally useful tool for learning as bots constantly remix and regurgitate news, history, and 80 year old blog entries. Due to this print media makes a surprise comeback with the youth in the same way early 00s digital cameras and tape decks did with gen Xers decades prior.

AI Authenticity

After years of chasing realism, the next big thing in AI wasn’t better output it was believable imperfection. In 20XX, the market shifted toward what developers began calling “Artificial Authenticity.”

People no longer trusted anything they saw, read or heard. Voiceovers were synthetic. Faces were composites. Text was statistically assembled. Everything was just too perfect and users had become fatigued by it.

Large Language Models were fine-tuned to ramble slightly. AI avatars blinked irregularly and some had weird twitches. Some were deliberately made to hesitate when answering, or to get facts wrong in a way that felt charming, rather than concerning.

A wave of new tools emerged promising “flawed-by-design” content emails with inconsistent punctuation and dose of dyslexia, pitch decks using Clipart, and synthetic voices that occasionally said “um.”

The Disconnect