What Does it Mean to Be a Man in 2018?

Someday soon in a place near here, not totally unlike this, an old man may rise and speak of simpler times.

The younger men might gather around and send for others, and they’d come running then hush to hear tall tales of great guys long gone.

Through greying beard, the old man might whisper, so as not to be overheard, of times not so very long ago when being a man was everything there was, and it was glorious.

Back when we provided and procreated and slept content; when we hunted and killed.

When we held the money and owned all of the votes and all of the women. When we built the roads and great buildings while inheriting everything and fighting the wars and running the countries and companies too. When we split the atom, invented the combustion engine and the internet and the Theory of Relativity. When we climbed Everest. When we went to the Moon because we could and how we went to Mars because Elon Musk was the ultimate embodiment of a start-up venture capitalist super bro/villain and he wanted to.

When the days were halcyon and Father Time was undefeated and being bigger and faster and stronger actually meant something.

When people ate meat and men made more money and the sex scene from Rocky wasn’t so obviously a rape.

When men like Roman Polanski roamed free and did as they pleased as they had in times before when everyone had believed in God, who was a man, and thought women were weak and made from the rib of a man.

Then the old man himself might hush, and pause for thought. That part could be difficult, and old though he would be, he may know in that moment he had never truly reconciled himself with exactly how and when it had all gone down. He’d merely know it had, and that it all made sense now, and that nobody could believe or otherwise conceive of a time before when it had not.

He might not want to go on. But once started, he may never stop. He might talk of transgender women weightlifting and bone

density and muscle mass and sperm banks rendering men obsolete. He might speak of feeling powerless in the age of ever-accelerating technological innovation. He might shake his soft fists at robot overlords for stealing the jobs of men.

When it was over, the other men might come to his side and together they’d weep and swear and speak of unintended consequences and how, sooner or later, enough would be enough and men would stand up and claim back what was rightfully theirs.

Funny or not, comedy has long proven a useful tool in revealing how people truly feel about the world around them. Comedians, obligated and emboldened by this, and spurred on by free speech and a licence to offend, thus test the boundaries of bad taste. But what does this mean for men, in a world in which so much is still at stake? Where the line between levity and lawsuit with gender has never been thinner and moves beneath the feet? Consider host Ricky Gervais’ opening gambit at the 2016 Golden Globes:

“But as I say, I’m gonna be nice tonight. I’ve changed. Not as much as Bruce Jenner, obviously. Now Caitlyn Jenner, of course. What a year she’s had! She became a role model for trans people everywhere, showing great bravery in breaking down barriers and destroying stereotypes…She didn’t do a lot for women drivers…But you can’t have everything can you? Not at the same time.”

Is a man allowed to find that funny in June, 2018, especially considering the February 2015 crash Jenner was involved in, and later settled a private lawsuit for, resulted in the death of Kim Howe after her Lexus was pushed into the path of an oncoming Hummer? The female-heavy crowd reaction edit doesn’t help in this respect, but it’s not completely without merit. For what it’s worth, Jaime Lee Curtis seems to appreciate the gag. Queen Latifah appears to stifle a chuckle. Cate Blanchett looks utterly shocked and finds it f**king hilarious. But what of this one stemming from a Jennifer Lawrence essay on the gender wage gap?

“Of course women should be paid the same as men for doing the same job. And I’d like to say now that I’m getting paid exactly the same as Tina (Fey) and Amy (Poehler) did last year. Now I know there was two of them, but it’s not my fault if they want to share the money, is it? That’s their stupid fault…It’s funny cause it’s true.”

This time Julianne Moore, Eva Longoria and Julia Louis-Dreyfus find themselves in the gun in the gaze of the world. All three laugh heartily. Mirth rings out all around. Gervais is killing.

You’d figure all of that would give a fella the green light to guffaw, but then you might be wrong. Humour comes with context, and Gervais is famous for this stuff. Even still another reaction shot, this time following a bit about the foolishness of certain media outlets claiming some celebrities would stay away from the Globes for fear of being roasted by the Englishman – particularly after their film studios had already purchased awards of their behalf – complicates matters more. Giggling and slowly shaking his head, in black suit and tie large and in charge, at a table filled with beautiful woman in a house he helped build, surrounded by stars he helped shine, sits a man that will likely never come to sit at that table again. His name is Harvey Weinstein. His presence in that scene, in that moment, in retrospect, is striking, and shows how much the world has seemed to change in the past two years. It’s hard not to wonder who in that room knew what, and when. But what’s more difficult, and perhaps more telling, is the question obscured by the large shadow the former studio head head’s casts when a light is shined back on that night. The one you only see when you look really closely, twice, like how you would with a Zapruder film, or a stereogram: Why aren’t there any reaction shots of men following Gervais’ quips about women?

Could it be in a politically correct world run amok with celebrity culture and virtue signalling and recreational social outrage, where Twitter flash mobs and new social causes are thick on the ground, and where everything from if the wage gap is a fallacy to whether men and women are equal in every sense, including biologically, is being contested, that men are under a consistently escalating threat of social reprisal for failing to check their natural impulses in line with the speed of progression? Perhaps, it seems, it works out best sometimes for the most people when everybody pretends they don’t know what is going on and look the other way.

Guys, it was one helluva run, but it looks like it might be over. The era of willful male ignorance taking the day could be done. There is no denying things are changing. Momentum, in terms of control of the narrative between the battle of the sexes, seems suitably against us. Feminisms’ three waves have crashed ashore, and more and more, the men who were around when the shore was dry are being dragged out to sea, and drowned. Gender politics now flow throughout the mainstream.The western world and further afield is increasingly awash with social and gender progression. Some of the creepiest and more famous among us are getting called out, shouted down, stood aside and whisked away for stuff that apparently seemed somewhat normal to a lot of people at the time.

In a post-Weinstein, post-Cosby, #MeToo world, men are suddenly in somewhat of a series of pickles. How much do we have to cede, and for how long? Existentially, what is a man supposed to strive to be in a world in which masculinity is an ever-evolving and shrinking construct forever at the whim of myriad, often increasingly powerful, feminine forces? It’s almost 20 years since Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden very much woke the middle children of history in David Fincher’s Fight Club, and another two generations of men mostly raised by women now walk among us. They’ve grown up in a world in which their privilege has been stated, not implied; where men are meant to be more docile and apologetic and made to feel a more appropriate level of guilt for past deeds done by earlier men. When rugby players aren’t meant to punch each other because head knocks in sport are more serious than previously thought and everyone is supposed to pretend men and women are the same when deep down inside almost everyone agrees almost instantly that they are not. For men, the question becomes clear and strikingly simple – what am I supposed to be?

Amidst the chaos, misogynist men appear to have an unlikely ally in the form of one of the leading figures of feminism’s second wave, Female Eunuch author Germaine Greer. The controversial Australian, who says she was raped as a teen, elicited a widespread public backlash earlier this year by saying most rape is just “bad sex” that should be punished by community service, rather than jail. She doubled down in a consequent interview with Geraldine Doogue on RN’s Saturday Extra, criticising the “general fog of craziness about the whole rape issue”, saying sentences are “excessive”.

“It seems now that we’re lining up for a war with men in which we’re never satisfied,” she said.

“We want them put away for longer, we want them punished for what is actually not an unusual form of behaviour.

“Non-consensual sex is common; it’s possibly practically universal in every long-standing relationship there have been occasions of non-consensual sex.

“And the actual definition of rape is that.”

The idea that rape is always an act of violence needs re-examining, she said, along with a review of sentencing guidelines.

“It’s between five and 10 [years’ jail] in England. I think the average sentence in Australia is seven – that’s huge,” she said.

“One of the problems is by making the sentences heavier you get a jury that is less and less likely to convict, because it’s so serious.”

These comments, and others about women accusing Harvey Weinstein of rape and assault spreading their legs for parts in movies and then “whinging about it”, are problematic in the extreme – something not lost in the inevitable, immediate backlash that followed.

Jennifer O’Connell of the Irish Times characterised Greer as a “one-time feminist firebrand turned anti-feminist troll” and “professional controversialist” who threatened to prove a divisive figure in women’s ongoing struggle for equality.

“#MeToo seems in danger of dissolving into futile inter-generational warfare between people supposed to be on the same side,” she wrote.

To her, and many other pundits, Greer has become a caricature of herself; a wildly hypocritical, two-faced female misogynist attempting to subvert gender equality away from a true 50/50 coin flip.

“Germaine Greer lashing out at women is, sadly, hardly headline news anymore; in 2012, she refused to apologise for saying [then Australian Prime Minister] Julia Gillard had a “big arse”. She has also said trans women weren’t “real women”. But this suggestion that the victims of sexual assault are to blame for being “afraid to slap him down” is the most egregious kind of ill-informed victim-blaming.”

Greer has often appeared to take controversial, minority opinions in the pursuit of notoriety. In another life, she was hailed as being at the forefront of a gender revolution. Now, decades later, she’s cast as a traitorous fence-hopper holding back the ongoing advance.

Her transformation – radical though it may be – begs another series of questions. As the world becomes more and more accepting of different genders, creeds, cultures and behaviours – sexual and otherwise – will there come a time when other women survey the grass on the other side and assess it as not being greener? When the majority has a collective epiphany that there will always be a minority group calling for more change, more quickly? Will they say enough is enough and draw a line? Where will men be standing once it’s drawn?

Looking back, the twentieth century can be framed by the evolution of what a woman was seen to be. Just 18 and a half years in, the same may be true of men in the 21st. Scholars are already studying the effects, and a counter narrative has been constructed.

“I have a strong feeling that masculinity is in crisis,” says Australian archaeologist Peter McAllister.

“Men are really searching for a role in modern society; the things we used to do aren’t in much demand anymore.”

The bull in the room is the number of jobs that will be lost to automation in the coming years. The internet is already awash with tidbits of ‘deindustrialisation’ and references to the replacement of something called ‘smokestack industries’ by technology being the tipping point which allowed women to enter the labour force at a higher rate due to the reducing emphasis on physical strength. Last year, The Guardian cited a McKinsey & Company study that found 30% of tasks in 60% of occupations could be computerised, adding: “last year the Bank of England’s chief economist said that 80m US and 15m UK jobs might be taken over by robots”. They went on to highlight a further PricewaterhouseCoopers report that found a “higher proportion of male than female jobs are at risk of automation, especially those of men with lower levels of education”.

It begs the obvious question: how good is it really being a guy in 2018?

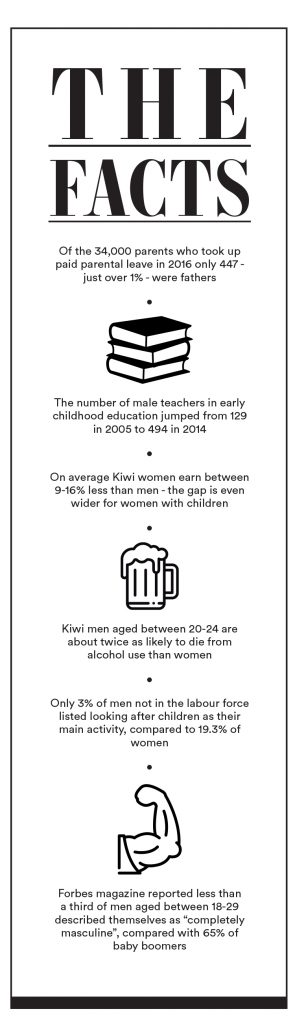

Globally, if you’re a man and you also happen to be gay, it’s a mixed bag. Gay marriage was legal in 26 countries by the end of 2017, but homosexuality was still considered criminality in 72 countries at the same time. In eight of those countries it was punishable by death. We’re in luck in New Zealand on that score and still hold most of the top jobs except for Prime Minister (Winston Peters’ cameo aside), but by many of the most important markers, we fall short of the fairer sex. A Kiwi male’s life expectancy nears three and a half years shorter than his female counterpart (83.4 to 80), while men register significantly higher rates of workplace injury, incarceration and suicide rates than women. Staggeringly, for every woman who kills herself in New Zealand, about three men do.

It’s a similar story for literacy and overall academic achievement, perhaps most importantly in the disparity between graduation rates at tertiary level. In 2008, two thirds of bachelor degrees went to women – the highest figure on New Zealand record. A NZ Herald article from the following year pointed out that “women have outnumbered men in the tertiary sector for more than a decade, but a new Ministry of Education report shows the number of men who finish bachelor degrees is falling.”

These results are backed up by data from the 2013 Census, which saw a similar pattern of female empowerment.

“The majority of employment growth in the higher-skilled occupations between 1991-2013 was for women; they are steadily increasing their representation in managerial and professional roles,” its conclusion reads.

“Occupational segregation between men and women is slowly changing, reflecting increasing labour force participation among women, and changing aspirations as more obtain tertiary qualifications and pursue professional and managerial careers.”

A similar advance can be seen in academics, where women appear to be extending their handy advantage.

“More women have been earning formal qualifications, and since 2001, women have been more likely than men to have qualifications.”

Part of this disparity is due to women pushing into traditionally male-dominated fields. In 2013, for the first time, men and women were equally likely to have qualifications in science and mathematics.

These recent trends mean women now have a higher percentage of masters degrees (51.1%), postgraduate and honours degrees (60.2%) and bachelor’s degrees and Level 7 qualifications (57.8%) than their male counterparts – striking statistics considering the lagging effect of the over-50s crowd. Indeed, there is a parity between the age groups of 50-64 and a large lead for men in the 65+ range.

This imbalance sees little signs of abatting – women have a wide edge in the numbers of people currently in study in every age bracket from 15-19 to 65+.

Women appear to be redressing imbalances everywhere.

The University of Oxford offered more undergraduate places to women than men for the first time in its history last year, while the University of Auckland announced a record 27% of its first year engineering students were female for 2018.

These academic results appear to be helping to redress concerns around pay parity. According to Stats NZ, the gender pay gap was 9.4% in the June 2017 quarter, down from 12% in the June 2016 quarter. That was the smallest gap between the sexes in five years, following women’s hourly pay rising at a faster rate than men’s. This is part of a larger overall trend that has been moving towards parity since the 16.2% difference recorded in 1998.

Remember that old guy at the start, with the beard and tall tales of great men doing wonderous things in building the world? The guy who was sexist, and wrong, and desperate, and to quote the immortal Norm MacDonald: “a real jerk”? If you had to guess whether he’ll ever exist, or which version of himself he’ll end up being if he does, which way would you lean? If you had to guess if he was already alive, what would you say? If you say yes, how old would he be? A toddler, or in primary school, or in college, or at university?

Could he be a recent graduate, or someone in his late-20s, or someone in his mid-30s like me? Could he be me? Is that the fate of a proudly progressive left-leaning media type in the age of sudden and steady social and cultural progression? Could I end up like Greer; overtaken by events like some second wave feminist overtaken by events and washed away by waves her momentum helped swell? Like her, and generations of men before her, will they be left to fall and lie prone on the wrong side of a coin flip like Aaron Eckhart’s twisted Two Face in Christopher Nolan’s 2008 masterpiece The Dark Knight?

Is that how it ends for all of us, victims of time irrespective of gender or anything else? Like Christian Bale’s Batman, is it possible to be proud of the progress that has been made yet wary of how far things have yet to go?

Two outcomes?

One choice?

Die the hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain?

There is a third possibility, of course.

Not everything has to be binary, especially when it comes to gender politics. Men can still thrive in a world of female empowerment, and it might just be better off for everyone if they do. New Zealand’s first family – not to be confused of course with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s New Zealand First family – provides an interesting, albeit exceptional, case in point. What odds of a bloke from 1918 imagining Aotearoa being run by a 37-year-old unmarried mother of one? Could he believe the first man, named Clarke Gayford, would be the primary caregiver after the first six weeks? How long would it take for him to figure out what a primary caregiver even was?

As unorthodox as it is, a recent OECD report suggests men taking more paternity leave could have dual benefits. It argues employers would be less reluctant to hire women of child-bearing age if men and women were roughly equally likely to take leave. The research also showed fathers who care for children early on, tend to stay more involved as the child grows up. It also stated children whose fathers participate more in childcare, tend to have higher cognitive and emotional outcomes and physical health. Mandating increased paternity leave for men is not out of the ordinary; in Iceland and Sweden, the “daddy quota” of 10 and 13 weeks respectively has led to a doubling in the number of paternal leave days taken by men.

The pendulum, so long favouring the fascinations of men, now swings back towards the middle. There’s disagreement about how far it has to travel, and how quickly it is getting there, or indeed if it will ever get there at all, but there is little doubt that it is heading with some speed towards equilibrium. The question then becomes what happens to that momentum once, and if, the pendulum reaches the bottom? Will women do what is natural for an oppressed minority which has finally achieved some semblance of parity, and push for more? If so, how long, and how possible, is a wild over-correction likely to be? Could that, in turn, lead to a male’s liberation movement; a counter correction? Or will women, kind and passionate and thoughtful souls that they are, achieve parity and instead stop? Will they begin to struggle more and more with feminism and feminazis the same way some proudly socially liberal on the left are tying themselves in knots after glimpsing, for the first time, a world that might just be going a little too far?

Will they see it’s possible to consider yourself progressive and becoming ever more so, only to find you’re not progressing at the same rate, and in the same exact direction, as the world around you? Will both sexes glimpse a postgender utopia and decide the pendulum doesn’t have to keep ticking from side to side before finally coming to rest?

Like that sad old man at the start, where you stand likely depends mainly on two things.

If you are a male and how long you’ve been standing there.