Fathering Greatness

Not long ago, on the east coast of golf-mad America, in North Carolina was a sneak peek into what could be simply described as the manufacturing of greatness – the American Dream on a conveyor belt. Filmed at the world-renowned Pinehurst courses was a collection of the world’s finest pint-sized golfers, and the stakes couldn’t be higher – for the parents that is.

Standing shorter than their bags at times, these incredible young golfers were logging scores to make seasoned adults envious. At times, though, they weren’t pleasing their caddying fathers who were all juggling roles as pseudo psychologists, coaches, caddies and dads; roughly in that order. Away beyond the tall pines were the doting mums, kept at meddle-free distance on the cart path with their cameras rolling for post-round analysis.

The Short Game programme that aired on TV was a portal into the world of what could be called the ‘Tiger Woods Effect’ – the engineering of golfing superstars from the earliest of ages in the quest for greatness. It’s nothing extraordinarily new, and turning the process into a reality programme was inevitable.

Within a minute of watching, the question immediately springs to mind: whose quest is it exactly?

As the pressure mounted on the young kids – one snotty child blowing his nose into his dad’s hanky – the true colours of the fathers came out, especially Rickie Fowler-lookalike, Bryce’s dad Mike, who appeared engagingly mild mannered at first. That was until a downpour affected his son’s short game. Dammit! As he lambasted his son for not being mentally prepared, we wondered what an 8-year-old like Bryce did to get himself ‘up’ for the big event.

Other dads on the course had differing methods – like Awesome Burnett’s father, Mark, who was swift to smack his hat into the scorecard in frustration after a missed bogey putt before praising his son for a round of plus five. He had caught himself in the nick of time – cameras were everywhere. Awesome, 8, already has his own website to go with the $30,000 annual sacrifice his parents make for his pressure-filled path.

Young Sachin was also struggling to keep pace with the leading golfers in the field, apologising profusely to his father, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” he whimpered as they walked off to the scorer’s tent.

This was serious stuff.

Back at the clubhouse, Mike broke down the nitty gritty of a pet prodigy project to those who would listen: “Hey, I’m a numbers guy… do you sell the house? I don’t think you do.”

Relating his position to the cartoon-like devil and angel on his shoulders, Mike then bared all: “the devil tells me he [Bryce] has to come and beat the rest of the kids,” he admitted before the numbers guy in him resurfaced: “I want a return on my investment. I’m not paying $15,000 for my boy to come 70th.”

Mike has a valid point. To the financially prudent, his son didn’t sound like a great investment when put like that. So, is there a chance for Bryce to reach the heights his father is expecting of him? Can he be made – and what would it take to turn him into – a champion?

The outlook of Bryce’s father is nothing out of the ordinary and it would be unfair to pigeonhole him as a glory hunter. He could well have the most admirable intentions, as most fathers dream of their offspring becoming a success, no matter what field they enter. A father’s wishes, although often concealed, can be intoxicating.

When watching Mike and the other caddying fathers, the question has to be asked, though: whose quest is it exactly, and what would it take for Bryce to be great? Greatness doesn’t come easy, so where does the quest end?

What is winning in life?

Greatness is realistically only reserved for a select few in life and the chances are ruthlessly slim when looked at statistically. The lengthy odds should never deter anyone from pursuing it but creating winners is decidedly easier with less potential for collateral damage. So, what can a father do to set the foundation for winning?

One of the first questions to ask is, what is winning in life? It’s a personal conclusion, but for most the answer is quick to find, as we’ve been conditioned internally and externally to reply without hesitation. For some, it’s money; for others, it’s their health and happiness; for others, it’s peer recognition. And then, for others, it’s just not worrying about it.

The sports-mad father could have fancied himself as a dab-hand during his playing days or had been an avid fan and this winning translation is easy: second place is first loser. It’s a cold and clear-cut way to separate the ‘winners’ from the ‘losers’, but an inescapable fact of competition. Likewise, the corporate executive at the top his tree knows he’s doing well from the zeroes on the balance sheet, and the megastar musician has platinum records and throngs of fans below his hotel balcony.

So, does greatness and winning have to equate to tangible trophy success? Can winning be living as a good person, contented with whatever cards they’ve been dealt or deal for themselves? The latter is hard to tally because accolades, money and rewards aren’t necessarily dished out in the public eye, beamed live to millions then relived in the press for days on end. Society has told us what greatness is, but it can be imbalanced. In an unmeasurable pursuit, like attempting to cure cancer or raising countless orphaned children, there’s an equal case for greatness no matter how obscured. One thing for sure – the distinction is crystal clear when it comes to the world of top-level sports and business. Results are publishable and, in many cases, indisputable.

Shooting for the stars or are the dreams and wishes for your son or daughter closer to terra firma? Is it happiness and health or accolades and accumulation? Is it not ending up in jail, on the streets or an avoidable early death? Is the success for your child, or is it for you? Winning surely has to be in the eye of the beholder, the child or the person at the centre of the study, because modern society already has its parameters set for greatness and nobody can even agree on that.

Is greatness about you or the kid?

Early on in their relationship, Andre Agassi and Steffi Graf’s fathers met each other for nothing more than a polite chit-chat as romance blossomed between their children. The fathers’ agendas quickly became clear, however, and within minutes, Peter Graf had stripped himself of his shirt to fight Emmanuel Agassi after barbs were thrown, initially about Andre’s need to have a slice like the 22-time Women’s Grand Slam champion. Agassi senior suggested it would have been 32 if Graf senior had taught his daughter Andre’s double-handed backhand… and the pair were close to blows.

Both fathers were renowned for their vigorous input into their child’s sporting success, but their own childish reactions to the pointless debate suggested it was about them. Extreme as this flar – up was, it still begs the question: whose success was it ever meant to be?

Agassi, an eight-time winner of Grand Slam events, summed up the differentiation in a 2009 interview with Spiegel Online. “What is right is that both of us were in our father’s hands,” he said, before clarifying one thing about his wife’s predicament: “Steffie loved tennis, sometimes got sick of it but loved playing.” Agassi, on the other hand, was outspoken for his conflicting hatred of the sport that happened to make him incredibly wealthy and famous. He felt liberated when he retired.

In his home country of Germany, Peter Graf was often seen as a ‘diabolical father’ who stole his daughter’s childhood. So, why single him out? That could be paternally true of each and every successful sportsperson, musician, scientist or other professional who dedicated their formative years to excellence in their chosen field. Perhaps it was his evasion of tax on his daughter’s earnings?

The pride in a child’s success is an easy justification for the prolonged dedication and commitment to a prodigy project. Most fathers brim with warm pride when their offspring win, defy the odds or punch a card that was better than ever previously achieved. Some dads are hard to please though, and in particular Agassi’s.

“After three losses in three Grand Slam finals, I finally won – against Goran Ivanisevic, at Wimbledon. When I called home and told my dad, he said: ‘How could you lose the fourth set?’ ” Agassi regaled of his hard taskmaster.

Setting standards high is a given on the road to glory, so, in Mike’s case, does he have a shot at making a profit on Bryce or is he spitting into the wind with his non-bankable asset? Can greatness be manufactured?

Are winners born or bred?

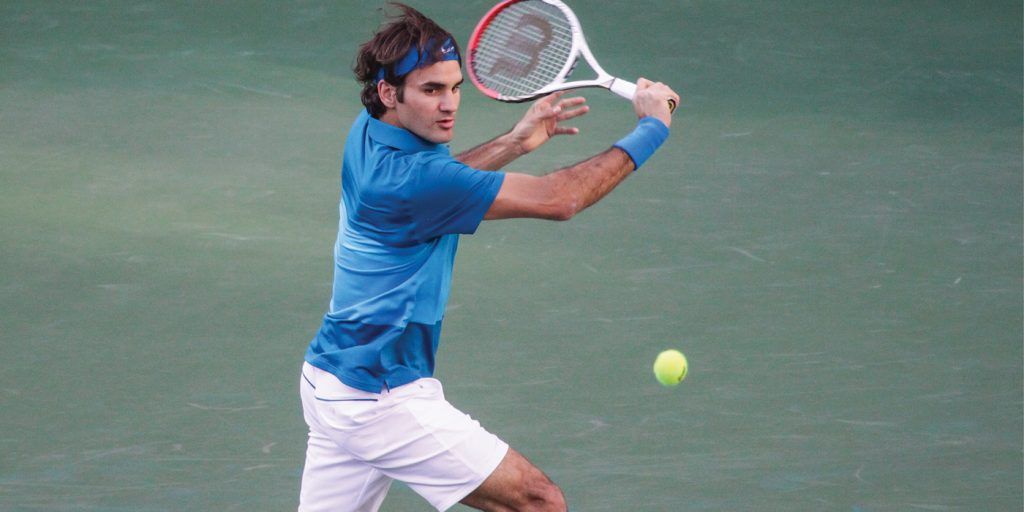

The one overriding theme in almost every storied success is, undoubtedly, talent – natural, pure, unadulterated talent. You hear of the musical ear as opposed to the tone deaf among us, or ‘he’s a natural’, ‘she was born to dance’. Roger Federer makes tennis look so effortless, so easy, and to put his stellar record down to what his genetic make-up is would only be partially correct; it’s merely a foundation. His talent was just the beginning of his journey to the top of world tennis. If Federer was born in an Amazonian jungle tribe, immersed in their ancient rituals, he wouldn’t be who he is. And, as Agassi also said, when discussing his own children, all anyone needs in life is “choice and opportunity”.

Federer’s big break in life was that his parents were club tennis players and he had the opportunity to watch them and pick up one of their racquets from an early age. With his undoubted hand-eye coordination coursing through his veins, there’s perhaps a good chance he would have had the ability to be the best hunter of dinner deep in the Amazon.

In Federer’s case, the environmental conditions were perfect for him to show his natural affinity for ball sports and especially tennis. Agassi, on the other hand, had a mobile with hanging tennis balls suspended above his cot and, later in his youth, an automated tennis ball dispenser ominously called The Dragon. Admittedly, Kiwi dads love to dress their newborns in All Blacks onesies, but there is rarely any serious prophetic intent.

Although it’s obvious Agassi had some natural talent, 2500 balls a day from The Dragon, at the non-negotiable behest of his father, wasn’t choice or opportunity. It was grooming, drilling, human pottery.

Agassi mitigates the severity of his stern tennis education with his father’s honourable intention to give his son a shot at the American Dream that he never had as an Armenian-Iranian immigrant, whereas Federer’s mother’s take on her champion’s introduction to tennis, however, sounds a lot like the average boys or girls get.

“We would go to play tennis, and Roger just picked up the racquet, and started playing. He loved the sport from the beginning,” she says, like it is no big deal to raise arguably the greatest-ever tennis player the world has seen.

Without being too monospecific, tennis gives us several glaring examples of the parents’ effect on their child’s born or bred disposition to a pursuit. It is an individual, lonely sport that from an early age requires the moral, financial and logistical support of a parent and there is almost a fanaticism attached to the journey of the game’s champions. It also gives us some of the richest contrasts.

Whatever their dissimilarities in their respective roads to the top, two ingredients to baking the champion cake intertwine – hard work and talent. The way Agassi played, and the way Federer still plays, shows their polarity. Agassi was a fighter, a known retriever of the ball who ran more court miles than most on tour. The Dragon spitting fire daily saw to that. Of course, talent was in plentiful supply too. Federer’s graceful style, which has won over many fans for its sheer aesthetic beauty, is as natural looking as the action comes to him. A contemporary of Agassi’s, who formed the other half on an all-American rivalry, answered the question of born or bred quite succinctly.

Pete Sampras, in an interview for Ace Tennis Magazine in 2000, was under no illusions: “in my case, I’d probably have to say born. At the most basic level, this game comes easily to me. I was born with the right genes, I guess.”

Sampras never discounted the significance of developing the mental game to succeed at the highest level though: “despite being given that talent, I did have to make myself a certain way, mentally.”

Nurturing that God-given talent

Children invariably enjoy things they are good at and once they’ve had the opportunity to try for themselves, the ball has started to roll and they will waddle after it. Even if you as a father can’t recognise a natural affinity instantly, you’ll soon understand by your son or daughter’s request to do more of the activity they are achieving at. Kids have a habit of surprising with hidden talents unearthed from days at school and unless asked about or stumbled across, we may never know what lurks within the kid who still needs help wiping peanut butter off their faces. Hidden talents are called that for good reason and the most unexpected are the ones that haven’t surfaced before in either mum, dad or the generation prior. Herein lies ‘opportunity’.

By default, parents look for or prise out those signs of genetic predisposition, but there is a chance Emmanuel Agassi could have been banging his head against a wall with a clumsy son who couldn’t hit the side of a barn door. Andre could have been a cross-eyed klutz when push came to shove.

When a child discovers their talent, whether it be dancing, drawing or darts, what on earth happens next? They’ve had the opportunity to find a knack and it seems they enjoy it – they want more, they are inquisitive. That’s the human brain’s reward system in its most simplistic explanation. They’ve now made their choice, so it surely comes back to more of the opportunity. Kids can’t drive the car to the local park themselves so it’s up to the adults.

This is a pivotal stage, as kids have a curiosity and a wonderment for so many things that if they cease to enjoy something, it’s often onto the next thrill. In New Zealand, sports coaching at the earliest levels has adapted to a more participation-based approach, much to the initial chagrin of the competitive. It hasn’t had an adverse effect as the cream is still rising to the top and the country’s sporting success is at an all-time high.

Getting a buzz from their chosen activity is the very essence of building the passion that is so important, and fathers might find their child’s intrinsic desire to become more accomplished may be better left to a third party. ‘When’ could be a case of your child outgrowing your knowledge or skill base on a subject or activity. We’re all experts… to a point, but a time is likely to come when the cheque book comes out and extra tuition is the only way forward. Poor Bryce may have cooked his goose by failing at his first World Championships hurdle.

Watching the cutthroat world of 8-year-olds’ golf says a lot about the differences of the American Dream and the Kiwi model, which is designed to promote widespread participation, even in the life-or-death national sport of rugby. It also asks the question again of whose success it is, and whether it’s a cultural anomaly or ingrained characteristic. It would be disingenuous to suggest New Zealand is free of the calculated fashioning of greatness but, pound for pound, New Zealand sport has the right idea and is having no problems churning out world class athletes as it is.

The will to win

If talent is an indication of what to pursue, and hard work enables that talent to be realised, then what is the next step, the next level?

Talent is everywhere you look, whether biomechanical, artistic or academic. Each year in New Zealand, a national under-20s rugby team is selected and roughly 80 percent of the young men are new to the team annually. Of that 80 percent that were good enough to reach this level as the best in their age group for that given season, only a mere handful ever go on to top-level professional rugby. Cull that number even further when talking about All Blacks honours. Of a Waikato Under-16’s representative rugby team from way back in 1997, only two of a 25 man squad have ever played professional rugby. Talent doesn’t guarantee a single thing, no matter how precocious.

Hard work and repetition will polish the talent like a gemstone, but as time goes by, how much does the individual want to retain the lustre? The true champions want theirs to be the shiniest and the most valuable, looking for extra ways to increase their sheen. It is as if there is no limit to the carat value for the highest achievers and it has to be flawless.

The will to win, the desire to succeed, is the difference and coupled with a hatred of losing, it’s a fearsome combination. Sadly for Mike, mortgaging the house doesn’t guarantee Bryce will end up with the adequate will to win, so how does it come about?

Kids are sponges with an innate desire to learn and they do so from exposure to behaviours, imitating what they see and hear. Other supporting theories try to explain how personalities are borne and how their personalities develop into success in later life.

German psychotherapist Alfred Adler in the last year of his life in 1937 believed, “that much of our behaviour and personality is learned, that it is the result of our nurture”. It’s also not widely known, but Tiger Woods has three older half siblings from his father Earl’s first marriage and Adler claimed ‘striving for superiority’ was a factor in siblings born second or thereafter developing a stronger will to win. The mental strength and insatiable desire to win was Woods’ 15th club in his golf bag, and his father Earl’s unorthodox distraction methodology on the practice greens may have also contributed to his mental fortitude.

Social conditions are also a strong factor in developing a will to win and the yearning to have something that someone else has can drive an individual to succeed. It’s what a person doesn’t have that can define what they end up with and there are many examples of children born into a world of entitlement who struggle to do an honest day’s work as adults.

All of the external motivation in the world can help but it doesn’t make the champion and it’s the mysterious inner drive that sets the best apart. What can help?

Let go of the leash

Unless you are a high-performing athlete, creator or professional, and your child has chosen the same path, you may want to keep your distance from hands-on tutelage. Sampras’ father Ted took the hint early on in the piece and enrolled the services of a professional coach. It was a withdrawal masterstroke.

By the end of a long day, many kids are likely sick of their parents’ voices and it’s nothing new or unusual for their attention to be fixated on a relative stranger who is organising an event or practice they are attending. What would dad know about passing a rugby ball?

Extending the hands-free approach has added benefits in the development of your child in his or her chosen skill, and Federer’s parents were certain of it in their son’s success. They even let him attend camps out-of-town of his volition.

“We are a close family, but Roger took the decision at a very early age that he wanted to play tennis away from home. We never forced him to do anything, we let him develop on his own,” his mother says in an interview for the UK Telegraph. ‘He made a lot of important decisions himself when he was younger and that was key to his success because he had to learn how to do things for himself. He learned to be very independent.”

This independence was emphasised in the analogy of Sampras, who, as a pro, rarely looked up at his coaching area for sympathy, advice or motivation. Sampras’ father, upon seeing his son glance up at him during a tough period of a match, would wave goodbye and go for a stroll. Sampras was certain this helped him become mentally self-sufficient from a young age, even if it was only spectator jitters that made his dad leave.

A simple letting go of the leash is a tough ask of a parent in an increasingly careful world, but there’s no learning like learning from mistakes and having no one to clean up the mess. In Japan, independence is taught concurrently with toilet training and it is not unusual for school starters to walk themselves to school. It helps that Japan is a safe country, where helicopter parenting isn’t common, yet chores for six-year-olds are normal practice, including brushing their younger siblings’ teeth and making their own snacks.

There is a Japanese anomaly, though. Love and affection to crying infants in every circumstance might sound like spoiling in the West, but the line of thinking in Japan is seen as promoting self-assuredness and independence. It’s an interesting contradiction to the ideals of independence, but they stand by it.