A 500-Year-Old Company In The Making

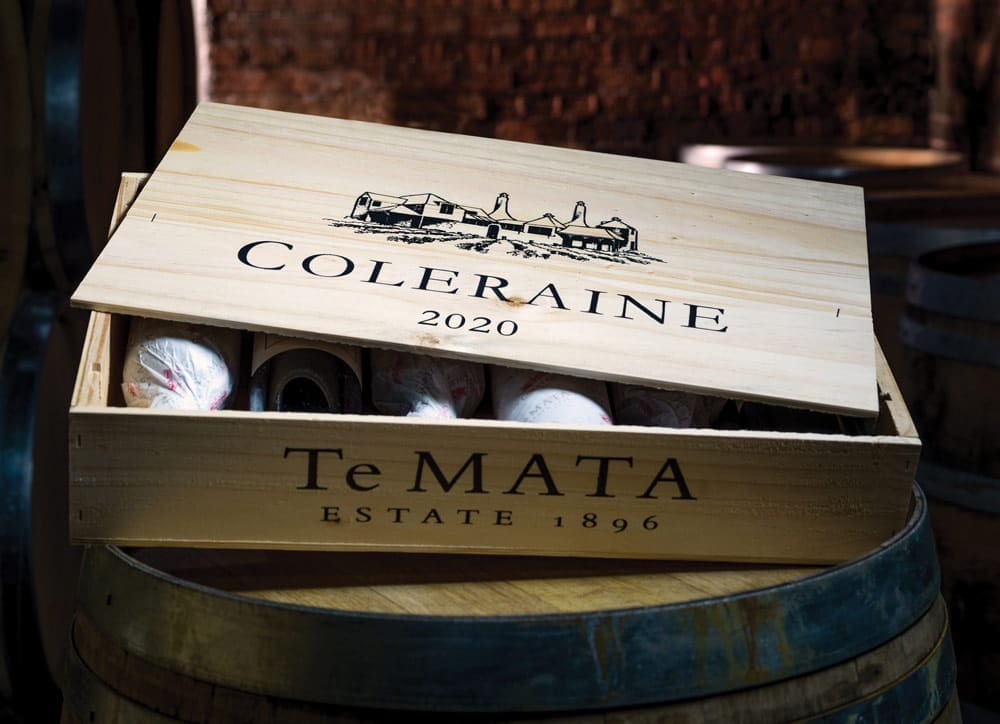

Te Mata Estate might be the oldest wine property in New Zealand, with 125 years of continuous production and an incredible global reputation based on a heritage of award-winning wines, but CEO Nick Buck isn’t living in the past.

He shares with us his vision for the future of the company that has been in his family for over 40 years, his lessons on leadership, the difference between being busy and being productive, and why profit isn’t always a good measure of business success.

If we look at your start, shouldn’t you be in banking now? Shouldn’t you be on Wall Street? What happened?

Well, it’s a good way of putting it. Certainly all the guys I was at university with all ended up in the financial field. That’s what I studied at university.

I was born in Wellington in 1970. My parents bought Te Mata in 1974, but for the first four years, it was leased out and, in the meantime, my parents moved to Auckland and my father ran what’s now Glengarry’s Victoria Park store. My older brother and I used to play in the wine shop and we’d play at selling wine to each other. We grew up around wine.

When I went to Massey University, I started out as an accounting major, which was a complete mistake, it was far, far too dull. I moved into finance because it was related to it, but it was a bit easier than accountancy and a bit more fun.

The whole time I was at Massey, I was working in the wine industry. I was working at Liquorland on the weekends. I worked for New Zealand Wines and Spirits, at night and on the weekends in the warehouse. And then I’d spend my summers coming home and working in the vineyards.

When I finished university, I decided to go and do ‘the OE’ that all the Kiwi kids did when they graduated. I went to London and got a job in the wine business in the UK for an import and distributor. There was a huge amount of turmoil in the UK wine industry in the early nineties and the company that I was working for was very aggressive, very fast growing. They swallowed up about three companies in the space of about two and a half years, each one successively larger than the one before it and bit off more than they could chew when they took on one of these companies.

There were receivers appointed and they took a look at my background and asked me to help out with the receivership side of things. I ended up staying on working for them for a period of time, helping wind the business up.

Sign Up To MYOB’s Free 30 Day Trial

That company’s largest customer was this big restaurant group that had 160 restaurants across the UK. They decided that they wanted to start their own wine importation and distribution side of it and approached me to do that for them. In the space of a week, I became the biggest duty paid wine buyer in the UK. I was travelling all around Europe, buying wine for them. It was fantastic. It was just like I was a kid in a candy shop.

But again, they were a very fast-moving company. After about four years working for them, they got gobbled up by a huge brewery company in the UK. That brewery company had 75,000 staff and so they had entire divisions of people doing what I was doing. I could see that my role was going to be subsumed by this company and either it wouldn’t exist or wouldn’t be much fun. By that time, I’d been living in the UK for a long time — I was a bit over London by this stage — and I wanted to get back to wine production.

I went and worked for a year at Château Margaux in Bordeaux, which is one of the first growths in Bordeaux and is one of the leading wine properties in the world. At that time it was being run by a guy called Paul Pontallier, who was a remarkable man. They were the first of the first really. I spent nearly a year at Château Margaux, living and working on the property.

I came back to New Zealand and back into the family business in 2000, at which point I was 30 years old and looking to settle down a little bit more. I thought:‘I’ve done well in this wine game long enough; I’d’ve been crazy not to be back at Te Mata with the family’.

Can you break down some of the skills or insights that you brought with you as a thirty-year-old getting back into the family business?

That time in London, with the distributors, I learned a lot about the international wine trade. Here in New Zealand, we don’t have the degree of exposure to the old-world of European producers that obviously they enjoy in London. London is a very international wine trading hub, has been for centuries. Wine is becoming so democratised. As it got better, the low end of the wine business got better than it was. It’s more reliable, it’s more appealing. You’ve seen the rise of the multisite retailers, multinational retailers and grocery chains and the like. The bottom end of wine has gotten broader around the world and that’s opened up wine in a way that it never used to, right across the Western world and increasingly into the developing economies of the world as well.

In parallel with that, and off the back of it, as wine has become more accessible and part of the everyday in these places, you’ve seen the fine wine market become way broader in its scope. In a place like London, that was a fine wine trading centre, but historically it used to service the upper class in the UK. When I was there in the early nineties, you saw the beginnings of the extension out from that. It was fascinating to see.

The other aspect that I learned from those experience is that you learn what not to do in terms of running a business. The wine businesses are incredibly cash hungry. It’s a very capital-intensive industry, in terms of the cost of holding stock, particularly when you’re on the production side of things; you’re also holding significant wine stocks. There are not many businesses where you would be holding two or three years’ worth of inventory at any one time. It’s something that people don’t factor in sufficiently.

Working in what was a distribution business and essentially a trading business, you get to see first hand the impacts of stockholding costs and when stock wasn’t being turned over sufficiently. Bordeaux was in many cases more eye-opening for me, and I think I took more out of it, in terms of personal learnings, which I was able to bring back to Te Mata. What I took out of it was more of a cultural learning, about their thought processes.

They have made such great wine for so long in a neighbourhood of other wineries who are also great, who are doing the same thing. They have a very, very clear understanding before they even start to make that year’s wine of what it is they’re setting out to try and achieve, and all the steps that they will have to go through to get there. They know what works to get there and they know what doesn’t get them where they want to be.

That clarity of thought and that experience, that you get to see an appreciation of how another culture conceptualises how they work — it’s really enlightening in terms of trying to translate that back to the wine industry here.

Te Mata is 125 years old, and my family has owned it for 40. In the scheme of what the Europeans do, they’ll be going for 500, 600 years and making such great wine for such a long period of time, it’s just different. We’re much more a fledgling beast still, but you can learn the principles from one place, and bring that back home.

On the growing side of things, people like my father, Peter Cowley and Larry Morgan did such an incredible job setting up such a strong foundation of the modern Te Mata, and we are determined to push forward with that. It becomes a real process of refinement of that foundation that they established.

That balance between the heritage and the modern technology is interesting. You can bring in say oxygenation to help amplify or speed up the maturation process, but does that necessarily undermine the wine-making process?

Our start point is quite traditional at Te Mata in terms of how we go about things, but because of the way New Zealand is still really open in terms of wine regulation and the like, we are also able to experiment much more broadly. It’s desperately important to remain open-minded if the goal is to drive quality further. It’s a bit like the America’s Cup line, what’s going to make the boat go faster? Be open to anything that might do that. But if it’s not going to do that, then why would you?

I relate that back to Bordeaux. I was talking about that technology and they said it didn’t matter, but the reality was they were spending a fortune making sure that they were actually masters of it. Certain aspects of things they knew really, really well, but other things by law, they’re not allowed to do for instance using irrigation in their vineyards. You could talk to them about various forms of precision irrigation to try and control the levels of stress in a vine and all the rest of it, so that you can absolutely achieve the very best outcome in the fruit for a given season. You can talk to them ’til the cows come home and they’d be fascinated to hear it, but they weren’t allowed to do it. They would have these walls put in place by regulation around them.

Do you have to make a conscious decision sometimes not to follow the money? You’ve got staff to pay for, you are focusing on creating the best quality wine in the world, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to the return that might be in the mass market side

Money’s not really the motivator. We’ve got a vision for what we want Te Mata to be, and money is just a means to an end to get Te Mata to that point. It doesn’t really come down to a decision between that for us at all.

Certainly, when we are making our wines we have got to make decisions about blending. We do all that blind because it would be horrible to know the costs as you are doing it. For instance, if you left out a particular blend, you’re potentially sacrificing a couple of hundred thousand dollars. It would cloud your decision too dramatically. You’ve got to set that aside. Otherwise, you won’t make the kind of wines that you want to try and push towards. So no, we don’t really let that get in the way.

In terms of that vision that you talk about, does that form the foundation of team culture? Is everyone buying into that?

I like to think they do. Certainly, most people do and have over the years. It’s evidenced by the fact we’re very fortunate to have a team that has been incredibly stable, and people have been with us for a really long period of time. I’d be foolish to think that everyone bought into it to exactly the same degree and that it was perfect for everyone. But anyone who sticks with us for a long period of time is doing so because they do buy into it and they want to be part of what we do. They see us all working incredibly hard ourselves in the business alongside them and can see what the family are doing. We consider them family, we really do.

We always have at least two big parties a year: one at the end of vintage and one at Christmas time. At both times, we don’t just gather our staff, we ask them to bring their spouses and their kids along. We want them to be family environments. We feel that their families are connected to us to a degree as well because their family member is working for us. They’re giving that person to us for a period of time and so we want the family to feel part of it as well. At our vintage parties and Christmas parties, there’s lots of kids and a whole big group of people. It’s the way we see it – we’re a collective, we’re a family.

I’ve seen some of the hours that you guys put in. Do you have to work at reigning that back sometimes; finding some balance, spending some time with your families, and not burning out?

I’m probably not a great person when it comes time for self-reflection. As I’ve gotten older, I look back and think, ‘Did I put too much into work? Was that a factor in my first marriage not working?’ But you can’t undo the past. I look at what I do today and what I know.

I’m very conscious about the demands we put on our staff because of that. Maybe I used to put too much on myself. I try to make sure that I balance my life personally a bit better now than I used to. I’m also very conscious of what we ask of the staff and the demands we place on them.

The seasonal nature of our business means that we have periods where those demands are massive, but it also means that we have the benefit of times when things are a bit quieter. We have to take that opportunity to try and say to our team members, ‘There’s a bit of a lull in your area at the moment, you really need to ensure that you get a break and a good break’.

The wine industry’s always been quite demanding. It’s not a very easy industry. It’s a tough industry and people are drawn to it with a passion and a love for wine. It’s very easy for it to become a wine bubble, where you’re working in wine and you’re talking about wine and your entertaining hours are all wine and food. You have to have a bit of perspective to that.

My parents tried to encourage us to play tennis as kids and they paid for us to have lessons. I did retain some of those early tennis lessons. My lovely wife, Lisa reintroduced me to tennis, which has become a sort of passion of my later life. I’ve also got a blended family — we’ve got six kids, my wife and I. I’ve got a lot going on in my life outside of work itself. I’ve got a lot of things that I can use to balance the strong demands of wine, trying to pull you all the way with all your attention. If it’s one of the kid’s birthdays this weekend, or you’ve got a genuine thing that you need to attend to that gets your mind out of the business for a period, that’s a healthy thing to give you perspective to bring back into your work.

As those family demands have increased for you and you’ve actually been forced away from work have you felt like you have lost productivity?

I probably had a sense when I was younger, that I needed to be doing those crazy hours to be on top of everything, but it is counterproductive. What you find is that by getting breaks, you actually get a better perspective on the business. I think we’ve become better at that in our business overall.

It is by no means an original concept, but it’s a very strong concept in organisational practises and theories these days, that diversity of view is extremely important. We’ve got better at that. It was the vision of my father and then it grew out from him to be his business partner, Michael Morris, and our winemaker, Peter Cowley. But these days it’s a much broader pool of that.

I’ve got a board structure above me that my father didn’t have. They’ve got a much more diverse range of views. I’m reporting to them, and therefore we’re making collective strategic decisions on the board level. Within our management group, we’ve got a much, much broader range of skills and range of people, and the voices coming into that are much better. You make better decisions out of all of that.

How would you describe yourself as a leader?

I like to think that I’m probably overconfident, probably one to push myself out there too much, but I think I’ve gotten better at that. I would like to think that if you asked any of the team, they would say that I listened to them and that I respect their input.

From what I’ve seen, that’s the best thing you can do as a leader. Surround yourself with good people and then let them do it. I think there’s a lot of truth in that, there’s so much to be said. As soon as you get that really solid advice coming in, you just know it.

You develop that trust or that faith to let them run with things. Once you’ve got that in your team, and you’ve got enough years of that, someone will come to you and say, ‘We’ve got a problem but we’ve thought about it and we’ve got a range of solutions’. If you can get to that point, your job as a leader is so easy. It’s done. You just know that they’re making sound decisions for you, and they understand.

At the same point, maybe that also goes back to having that vision that we talked about, that there is that clarity around that too, that everyone knows the direction in which you’re trying to head.

Speaking about the complexity of running a business like Te Mata, what solutions do you use to keep track of it all?

When my father had taken on Te Mata, his business partner, Michael Morris, was a very, very successful accountant in New Zealand. He ended up being the New Zealand chair of KPMG. He was a very astute man and a fantastic accountant and a leader within that accountancy world. He ran a lot of the backroom financial stuff at Te Mata; he set up the structure of it and organised that part of both the administrative side of accounting and finances and then the oversight aspects of it as well. He was old school and it was all pencil and paper.

For our day-to-day stuff, the admin backend of all of that had gotten very hopelessly outdated and we decided that we really needed to overhaul it, modernise it. We moved into QuickBooks, but very quickly got extremely frustrated with it and had grown beyond it. We were looking around for good packages and at that point, MYOB stood out. They were head and shoulders above anything else at the time for this part of the world and treatments of the New Zealand situation.

We’ve got a relatively complex product,a highly regulated product. So you’ve got to account for all the excise tax side of things. You need very strong stock-keeping aspects to it, very strong taxation bits of it, record keeping parts to it. And then, because we were by this point beginning to export to a lot of countries, and we export now to 45 different countries, we needed an international bit to it as well.

MYOB just stood out for a whole host of reasons, ticking so many boxes of what we needed. We’ve really grown with them over the years. We like the recording aspects internally, the controls that we get, the flexibility that we get out of the package. So there are a bunch of things that we really enjoy about it.

Could you describe any tangible benefits from systemising that aspect of the business?

Part of our drive to make great wine is underpinned by the process of refinement. We are always drilling down into our operations, breaking vineyards up into different varieties, different plantings, different pruning systems and finding these smaller and smaller blocks within them. We had reorganised our wineries. Hand-in-hand with all of that is all the record-keeping behind it.

We want to understand the last dollar of what’s gone into our efforts so that we can work through and understand, if we did this to it, does it make it a better wine? How much did it cost us? Could we achieve the same thing by doing it in a different manner, just as effectively? If we spent more on it, would we get more benefits? Could we afford to do this across more parcels elsewhere to try and improve the quality further?

What we enjoy about using MYOB is that flexibility. That ability to customise it for our business needs and then drill down into that data and get reporting insights back out of it so that we can really analyse individual things. It means that we can understand these aspects of our business to a much, much greater extent. And the quality of that information, again, gets back into that point I was making about decision making.

Even though New Zealand might be a fledgling industry compared to the likes of Bordeaux, is there still a certain weight of responsibility on your shoulders not to bugger up a 125-year-old legacy?

To be fair, I don’t think about the past. The past is gone. I work with my two brothers in the business as well: Toby, and my older brother Jonathon. Jonathan’s got kids, I’ve got kids. It’s more about the future that I’m always looking to than the past.

When I first took over as the CEO back in 2013, there was a sense of ‘Dad’s done such an incredible job and I don’t want to stuff up what he did’. But the reality is, all I see is opportunity in front of us. There’s so much more we can do, and not only on the wine-making side of things; on the wine production side of things, in the vineyards and in the winery, but also forward into the markets.

I’m extremely optimistic about the future, not only for Te Mata but for New Zealand wine.