Amidst The Ruin

To capture a ruined space for the sake of art would be somewhat of a melancholic experience for a photographer. It may evoke depth, reflection and loss – if caught in the right light.

Every city has its history and mystery, and it’s only a handful of artists that actually go forth into these places to seek it. Detroit is one of those cities, and the beauty lives inside several of its oldest buildings and industries. Renown for its association with the motor industry and the decline of its suburban environment, Detroit is rich in storytelling and life, even if the hollowed buildings that highlight its postcolonialism don’t speak in this same language.

It’s sort of like dragging a stylus over wet cement. Even when that cement is used to hold up the infrastructure of a city, the delicate inscriptions will still survive. The French artists, Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre thrives in these spaces – disorientated and drained with odd yet familiar light.

Since meeting in 2002 and becoming certain allies, they’ve travelled the world searching. They’ve set up galleries around Europe, exhibiting their work over the years and are currently in Paris exhibiting their latest collection called “Budapest Courtyards”. They launched their second book of photographs in 2013; the first came out in 2010.

We sat down with both photographers and asked them about their intentions and love for broken things to photograph.

Anything broken can be fixed, especially for the sake of art. Anything can enter a ruin, but exit a masterpiece.

What first got you both into photography?

We first started shooting using 35mm, back in 2002. We almost immediately worked on documenting modern ruins. By nature, all those places were about to change and that’s what urged us to document them in the first place.

What motivates you to create?

When you’re first visiting a ruin, it’s a mix between excitement for the discovery and apprehension. It’s a kind of alternative journey that brings you a sense of geography and history that you could not experience in such a powerful way.

We like to find places and stories that are in someway staying outside of the documented area, outside of the official history. All of this make those places some kind of unconscious and invalidated history. As photographers it’s interesting to try to put those disappearing fragments together.

What are your biggest inspirations?

Among photographers, probably the Becher’s, the famous German couple who documented the endangered industrial structures for more than 40 years. Their work is an example of tenacity and devotion. It’s both a piece of art and an incredible document.

What do you want people to feel when looking at your images?

We first try to convey the feelings that we got when we were visiting those places. It could be a mix of excitement from the discovery of it, melancholia, calm, etc. We like the people to feel like you’re able to read the different layers and perceiving in one place different temporalities. It gives a certain sense of time. It’s all these things that create conflicting emotions and it makes those places so fascinating and moving.

What tools do you use to create your photography?

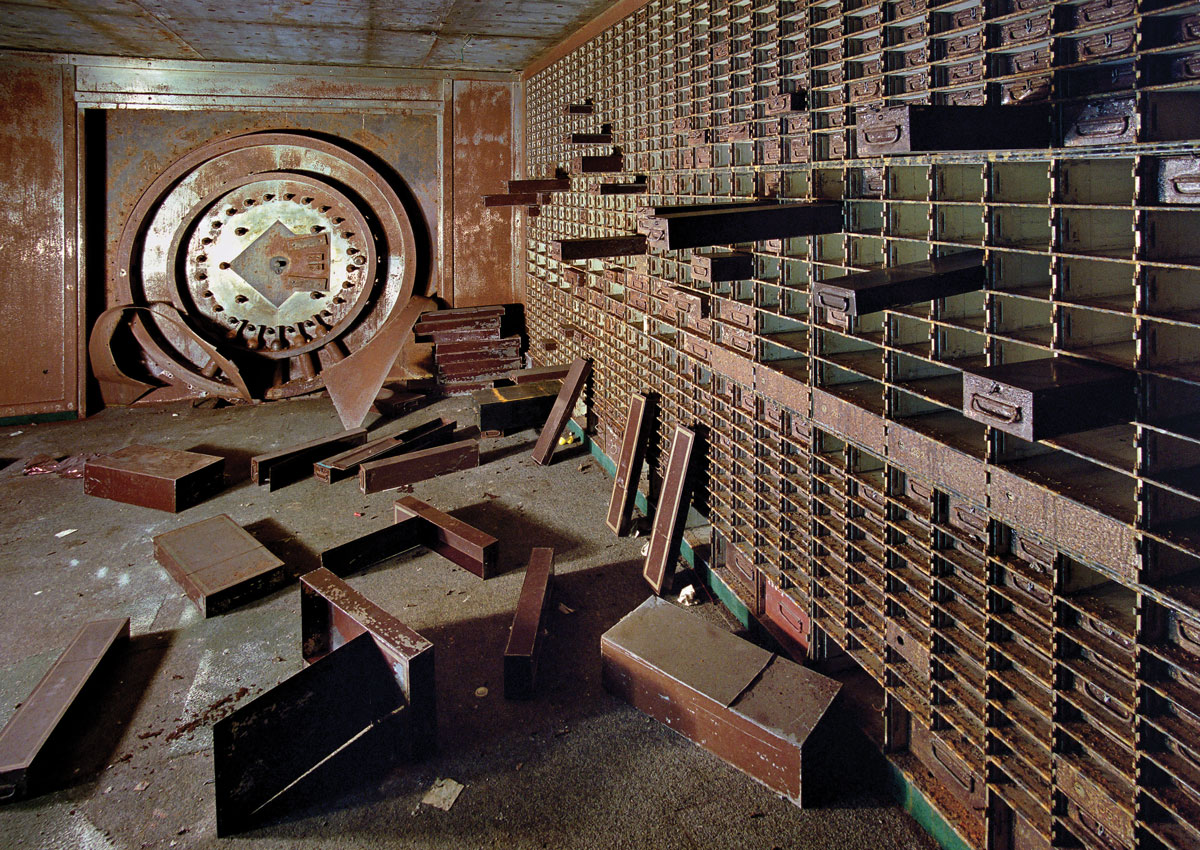

We’re using a small 4×5” camera, which is quite light. That allows us to be quite mobile on one hand, but we also get a great definition and the ability to shift the camera to keep the real geometry of the places we visit. The strength of the images probably comes from the difference between the framing, which is most of the time quite formal (like almost an architectural drawing) and the state of dilapidation of the places we visit.

Then by doing large format print, you really give a sense of the monumentality of those ruins.

What sort of advice would you give budding photographers?

Do what you like, it might pay some day, just keep going on. All the good subjects of any kind of photography needs time to do and perseverance.

For instance, the work on Detroit took us 5 years to achieve. We’re currently working on a series about former American theatres, documenting their evolution and changes through times, for the past 12 years. We’ve been saying that it’s going to need one or two years more to complete it for the past 7 or 8 years already! A book should come sometimes in the early 2020’s… probably.

How do you get inspired by places to photograph?

It’s a mix between light, atmosphere and architecture. Having visited hundreds of different places, we became more sensitive to the detail that makes each place unique. Then we discuss and try to find the right frame and the right distance before settling up the tripod. We try to find what image could possibly epitomise the place by itself.

Why Detroit? What was the attraction?

There were simply more ruins in Detroit than in any other city. Ruins and especially those from Detroit are visually evocative, but to us the context and historical background of the city makes them really moving. In a way it allows us through the filter of ruins, to speak more largely about America and our recent history.

You could start on something which appears anecdotal in a first place and then open it up to something much more larger. For instance the old Michigan Theatre was built at the same location where Henry Ford created his first car, and the movie palace was finally turned into a parking lot; it’s really telling.

Some of your most hard-hitting images are not of large-scale buildings, but of abandoned atriums and rooms. Did you aim to have that intention of abandonment in your images?

Yes, it surely is paradoxical to see all this abundance within the abandonment. The images that are the most telling are probably those which give both a sense of intimacy and monumentality and also familiarity, as we feel like we could have been living in those spaces as there are so many artifacts remaining. That’s what is the most moving and disturbing.

Do you think, in some way, that there’s an industrial revolution happening in Detroit at the moment?

There are surely changes happening right now in the car industry. Ford recently bought the old Michigan Central Train Station, which has been vacant since the late 80’s, to make an innovation center. It is obviously a very strong symbol as the train station was the visual embodiment of the whole Detroit situation. The car industry is still huge and it would take years to be remodeled. It would really go in that idea of reversing the narrative of a falling Detroit which seems to have work in a way, despite the fact that vast portions of the city, like the East side, still remain in ruins. But there is surely a huge effort from various investors to change the city now.

What do you think makes a memorable image?

To us, a good image should be first of all readable as an historic document and then as a broader metaphor as well.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

As self taught photographers, we’ve never really been given advice. The great thing with that is that we never really feel crushed by the amount of great photographers and influences. We basically did what we wanted, which is quite a luxury as photographers.