Finger On The Pulse

It’s no secret that monitoring your blood pressure can help to save your life. But what if we told you there was a new way to measure your pulse that didn’t just focus on the right now, it could also potentially predict your risk of heart disease years in advance? And enable you to manage it accordingly.

MRI scanners, T-Cell treatment, laser surgery…the knowledge and tech behind medical science has advanced in leaps and bounds over the last few decades. And yet the humble blood pressure monitor has remained pretty much the same for more than 100 years.

Sure, most modern day models have a digital readout – we even have one in our house that my wife bought when she was pregnant – but given its potential importance, the apparatus itself remains a fairly rudimentary means of checking your health.

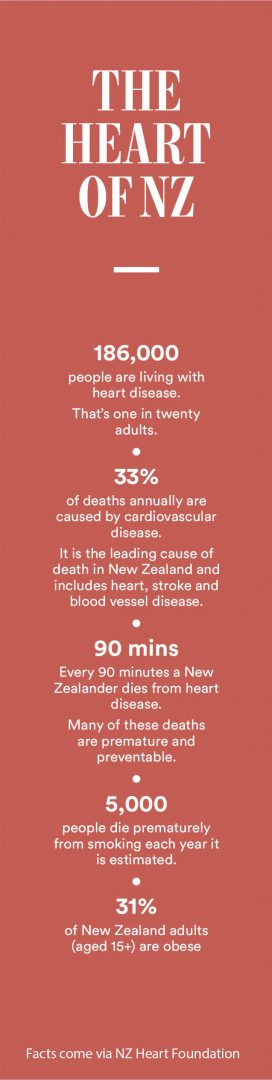

All of which seems rather odd when you consider that heart disease is still New Zealand’s number one killer, and by some margin too. According to the NZ Heart Foundation, someone dies from heart disease in this country every 90 minutes. In fact, 33% of all deaths annually are caused by cardiovascular disease, and right now 186,000 Kiwis are living with its effects – that’s an astounding one in twenty adults.

Stress and heart health

Stress and heart health

Life wouldn’t be life without some degree of stress, at home or especially at work. But when this stress lasts for prolonged periods of time, it can seriously damage your health. Long-term stress means higher levels of adrenalin are a constant, which in turn increases your blood sugar, blood pressure and tension levels. Unsurprisingly, this in turn increases your risk of heart attack or stroke.

In other words, when stress is a constant, your body stays on full alert, ‘fight or flight’ mode for days, weeks, months, even years at a time. And while more research is needed into the link between stress and coronary disease, it is certainly true that stress may affect our behaviour and other factors that increase our risk, such as higher cholesterol levels, loss of energy, physical inactivity, or smoking and drinking alcohol to ‘cope’ with the pressure.

Given all this, you might find it surprising that government health agencies and GPs aren’t focusing on more scientific ways to combat the ‘great Kiwi killer’ above the usual messaging of lifestyle, exercise and diet. That’s not to say they don’t care, or that there haven’t been any positive initiatives. But what about the tech to back it up?

Been there, done that

“The trouble is that new medical technology is very expensive until it becomes commonplace,” says Dr Craig Walsham of CellWorks, a clinic specialising in personalised health programmes and chiropractic services based in West Auckland. “When new technology gives practitioners more data about a patient’s health, it requires significantly more clinical attention and resources to implement interventions. The current approach is focused on broad lifestyle and diet advice which patients can then easily confuse with health fads and trends.”

When it comes to poor heart health, Craig has first-hand experience. At the age of 42 he suffered a heart attack which very nearly killed him, and very definitely changed his life. “After suffering complications from angioplasty, I was left really unwell, long after the heart attack.” Yet today, through utilising his own programmes, Craig is the healthiest he has ever been.

“I knew I had a family history, and that there were genetic factors at play, but I didn’t want to be dependent on medications for the rest of my life.” So, incredibly, Craig made use of genetic testing and blood pathology to determine the root cause of his own heart disease, managing any issues himself through diet and lifestyle. Isn’t that risky?

“If I get it wrong, I die,” he says. “It’s been 7 years.”

Combining his personal and clinical experiences, Craig has now developed an Executive Health Assessment, a suite of tools geared to corporates, companies and private patients wanting to identify risk in the workplace, and beyond. Using this data, specific interventions are able to be made. He has also recently invested in a new piece of kit, the Sphygmocor, like a blood pressure monitor supreme, which he believes could be a game changer.

The heart of the new tech

So what’s so special about the Sphygmocor? Well, your common or garden blood pressure monitor only records brachial blood pressure in the arm. In clinical practice it has proven itself a useful and viable tool, although there are also suggestions from some quarters that it can be anywhere between 20-50% inaccurate. A rough guide, in effect.

The Sphygmocor, on the other hand, uses highly sensitive sensors (similar to those optometrists use to gauge eye pressure) that measure the entire pulse wave of your heartbeat, picking up changes in the whole arterial system – data that a normal blood pressure check simply isn’t able to provide.

The makers of this new tech also claim their pulse wave analysis “is able to identify changes such as artery stiffness 7-10 years before we would normally see changes in a Brachial blood pressure that would raise clinical concerns.” Bold claims indeed. But do they actually stack up? To find out more, I decided to ask for a second opinion.

Second opinion

Associate Professor Michael Skilton (BSc (Hons) UQ, PhD Syd, FCSANZ) leads the Nutrition and Cardiometabolic disease research group at the Boden Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise and Eating Disorders, and the Nutrition and Cardiovascular Health Project Node at the Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney School of Medicine. That’s a lot to pack onto a business card.

Michael and his team have previously used the Sphygmocor device in research into obesity and weight loss, and have recently started working with the company that makes it to develop new algorithms that will enable accurate assessment of central blood pressure in children and adolescents.

“High blood pressure is one of the strongest modifiable risk factors for heart disease and stroke,” he says. “It’s closely linked with lifestyle factors, including obesity and poor diet. Blood pressure is easy to measure, and there are a number of well-established treatments that lower blood pressure and consequently prevent heart disease and stroke.”

“The Sphygmocor devices use advanced algorithms to calculate the blood pressure in the aorta – the main blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart. This is potentially important because it is this ‘central’ blood pressure in the aorta against which the heart must pump.”

The doctor will see you now

Michael is perhaps understandably cautious when it comes to endorsing the medical benefits of the product overly before he has conclusive proof. But being an irresponsible journalist, my own personal interest has been piqued. So what now?

Well, instead of waiting for the full research data to roll in, I decided to take matters into my own hands and walk the talk – by offering myself up as a test subject…

I swear I have also noticed an improvement in my energy levels. In fact I hadn’t realised just how sluggish I was feeling before. To be honest, I’m usually fairly cynical about such matters, but maybe there’s something in this after all.

The Guinea Pig Test

Before we start strapping me in, I should probably tell you some family history. At age 49, thus far in my life I have not had a heart attack. But like Craig, I do have a family history. My Dad had a mild heart attack at 55. He smoked at the time but was also working 16-hour days up to 7 days a week in a high-pressure sales job, which I always tell myself was a major contributing factor. In addition, at time of writing my Dad is still going strong, well into his 80s.

Then there’s me. Pushing 50, ex-smoker now vaper, no real exercise to speak of, a decent alcohol consumption but a relatively stress-free job, beyond the usual concerns of a freelance writer. In the last few years I have begun to notice the gentle physical deterioration that comes with age – ‘God tapping you on the shoulder’, John Cleese calls it – but thankfully nothing too drastic.

Nevertheless, I am intrigued as to what insight this series of weekly tests with Craig might provide.

VISIT 1

“There are only about seven of these machines in the country,” Craig says proudly as he tells me to lie down and relax. He straps the band around my arm much as you would with a standard blood pressure test and instructs me not to move or talk during the process.

The Sphygmocor device itself is a small machine not unlike an electric weight scale in appearance, connected to a PC on the desk. Craig presses the button, and we’re off. The band inflates automatically and holds, before deflating in short bursts. Then inflates again, this time easing off in a single continuous release. It’s all over in little more than a minute, and it’s time to check the screen for my results.

Graphs show upper and lower ends of various measurements. I’m rather relieved to discover that mine all seem to be within the parameters. Based on my central pulse pressure and arterial stiffness I have the heart of a 46 year-old, apparently, which all seems in order.

But then Craig shows me his own chart. For a man who had a heart attack seven years ago at 42 and nearly died from complications, it’s pretty impressive. According to his pulse measurement,

Craig has the heart of a 35 year-old, a figure that has also decreased over the last few months. How’s that done then? Through a program of diet and exercise tailored for his genetic make up, apparently – and with the help of some natural vitamin supplements such as garlic, fish oil, magnesium powder and something else called CO-Q-10-Plus which Craig assures me helps to maintain cardiovascular health.

I’m to take these daily before my next visit and also make a point of going for a half-hour walk at least 4 times in the ensuing week, something I pretty much do anyway (ahem). I’m intrigued, with an air of healthy skepticism, but let’s see where this gets us. He also gives me my results on a memory stick, so I can share them with my GP or a cardiologist, should I wish.

VISIT 2

After initially suggesting I have more of a cruisy job than most, the day leading up to my second test proves to be quite stressful – I have deadlines to meet and much to do in a very short space of time, quite apart from the usual daily chore of getting kids out of bed and off to school on time (sadly two out of three children have inherited my genes there). So it will be interesting to see my results.

This time as I lie down and relax, I manage to feel like I could easily drop off to sleep, until Craig presses the button and here comes that familiar squeeze on the arm as the band inflates. Think happy thoughts, I say to myself.

The results are encouraging. According to Craig my heart is now perfusing more blood than last week, which means there is more of it getting into the cells of the aforementioned organ, and my Sphygmocor heart age is down to 42. Not bad. Even Craig is enthused. Apart from the supplements and a little bit of walking (I’ve been parking up short of my destination and walking more in the last week), I’ve really done very little different to my normal routine. Lets see how we go from here – if this carries on, in another 6 weeks I will have the heart of an 18 year-old. I wonder if that will make it harder or easier to get out of bed in the morning.

VISIT 3

My final visit a week later proves to be much the same as Week 2. The graphs have leveled out, Sphygmocor age of 42, but the figures show that my heart definitely seems to be performing better.

Personally, I swear I have also noticed an improvement in my energy levels. In fact I hadn’t realised just how sluggish I was feeling before. To be honest, I’m usually fairly cynical about such matters, but maybe there’s something in this after all.

Craig tells me that marked improvements in some of the factors measured by Sphygmocor can occur within the first couple of weeks. But with regular exercise, nutritional supplements and occasional monitoring, there’s no reason why my heart age can’t be reduced further. In truth, I feel younger already, and I was the last person who expected that.

Want to reduce your blood pressure?

If you’re concerned about hypertension, we’ll end with the advice of Associate Professor Michael Skilton:

“Discuss your blood pressure with your GP or a registered health professional, and work together to find solutions that will work for you. Be prepared to make difficult decisions – committing to regular exercise, losing weight, and eating a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean diet or a plant-based diet) may not be easy, but they will assist you in achieving the maximum benefits. It really is never too late!”

Many thanks to:

Associate Professor Michael Skilton, The University of Sydney School of Medicine.

Dr Craig Walsham, Chiropractor, Cellworks.

cellworks.nz