How To Push The Boundaries Of Innovation & Technology To Create Global Solutions From New Zealand

One of the values of Rush is how to push the boundaries. It’s something that we instill in our staff and it’s something that’s culturally really important to our company. So what I mean by my topic is, how do you do something totally new? How do you do something innovative and apply technology and get a result that is represented on the world stage, not just in New Zealand?

I was thinking about the audience here today and I wanted to make sure that I imparted something that was really useable, but I just couldn’t get the title out of my head.

If you take a corporate bingo card and you start to talk about weasel words – because innovation draws that out in people – there’s a lot of people who can talk about innovation and doing stuff, but it’s actually hard to prove that it works. And it’s such a wonderful word because it sounds so corporate bingo-y. If you throw something like ‘leading-edge, technological solution that has lots of synergies,’ I think with that card, the only thing it’s missing is ‘blue sky thinking’.

So why would you want to listen to me? Why should you pay any attention to the developer with the topknot sitting on the stage? What have I got to say that’s different from anybody else? What I can tell you is Rush’s experience.

I’ve been there since day one. I’ve been the janitor, the CEO, the CTO, the sales guy, the guy that screwed up, the guy that recovered a project, the guy that has done the client management. And it’s taken a long time. I’d just love to share that experience with you.

In our history, we’ve done a lot of world firsts. The key thing is, we’ll keep doing that. We fully believe that and we’ve done it again and again and again, and we’ll do that all day long.

We’re about 100-odd staff, and we’re continuing to grow. We’re really technology focused, but we have a human-centred design element that’s been added to the business recently. We love to work on meatey problems.

One of our core value propositions and our purpose statement is: how can we use technology to better serve humankind? Because there is a responsibility. When you have incredible developer privilege, you have to be careful about what you work on.

That’s not to say that everything we work on is really going to move the needle on one of the great social issues, but we are very conscious in making sure that we don’t contribute to something that has a negative impact on the world.

In terms of the origins of the company, I’m a trained engineer in computer graphics, I actually started out in games. I love video games and building video games and all the technology underneath that, and the company’s taken some of that DNA.

We use to work for the likes of Microsoft and Disney, delivering videogame products, doing stuff on XBox. Pretty heavy engineering and lifting. Even more recently, we’ve worked directly with the Google Brain Team, out in Mountain View. We’ve been working with engineers to deliver a world-first that was actually on the Google I/O keynote.

If you look at Z Energy, a company that is very corporate and not really a technology company, we’ve also delivered fantastic, innovative solutions for them. Our [Z Energy] Fast Lane project is one I really like to talk about because this was something that was talked about for 15-odd years. It made sense, the idea wasn’t that necessarily novel, but getting it done was extremely hard and somehow Rush and Z Energy were the first ones in the world to do that for fuel.

Timing was a key part of that, people had to be comfortable with how you pay for fuel and the Uber-risation of the world. Fast Lane is a fantastic concept that’s executed really well, and is extremely innovative on top of a corporate culture that has a lot of legacy systems.

The idea behind the Fast Lane is basically a user drives in, they have preloaded their credit card through an app, we use a camera system to read and recognise their licence plate, and then within two seconds, anywhere in the country, it unlocks the fuel pump and says, “Kia Ora Danu, 91 ready to go.” You pump your gas, you get back in your car and you drive off. You never touch your phone and you never touch your wallet.

This is the best customer experience you could possibly get out of something like that. We did this from kick off to live first use in 13 weeks.

With Animal Check Ups, this one I love a lot. This one really talks to doing things better. This was a well-awarded project with Starship Hospital. They were doing a renovation of their reception area. It’s an emergency ward in a hospital for kids, that’s an area of really high tension, real anxiety and unrest.

We applied human-centred thinking to observe the area and we came up with a solution that not only helped the clinicians do a better job and simplify their job, but also help parents manage their kids, and also help kids be distracted in that moment where a brother or sister might be sick or they might be waiting for an appointment.

Again, we started with a simple concept idea, and applied design thinking. We used simplistic methods of testing really complicated technologies to prove that, yes, this fundamental next step is going to work and therefore we should invest more to progress this idea.

Those are two really good examples and I didn’t want to go into those two too specifically because the real value for you guys is how do we keep doing that and how can you transfer some of that knowledge to be useable by yourselves in your day-to-day.

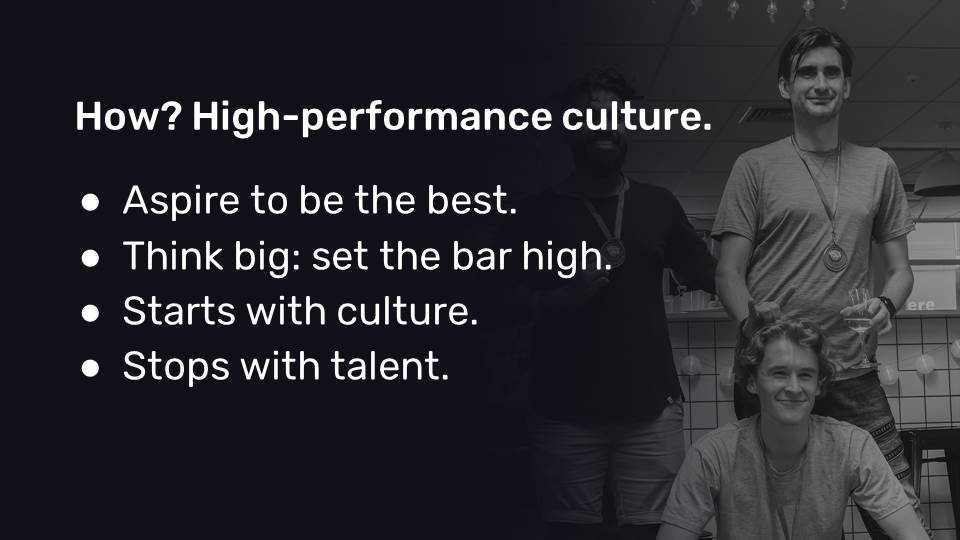

I think one thing is you have to want it. You don’t have to be there from the start. From day one of Rush, we didn’t necessarily have a high-performance culture. It was just me and I was working in a bedroom alone, and my Mum came in and said, “You’re talking to yourself, you need to get an office.” That’s definitely not a high-performance culture, right? But in my head, I wanted it to be a high performance culture, and every person that I hired, I wanted to do better.

Dr. Ray Thompson, who passed away, was a cornerstone shareholder and a great mentor to me. He said something that stuck with me: “You should always aim to be the dumbest person in the room.” And what he meant by that was every person you hire should be smarter than you.

I joke and half laugh in the office, I’m like “Haha, I would never get a job here.” And everyone’s like “Oh Danu, you’d get a job,” and I’m like “No, really. I probably wouldn’t get a job here if I applied.” But it’s that aspiration to be the best.

You have to think big, you have to set the bar high. Not just in New Zealand, you have to compare yourself to global companies and then blow past that.

We have it in us in New Zealand culture, we absolutely have it in us. The Cricket World Cup reminded me of one thing, we over-index so hard core in sports. It is evidence that we can really win in business as well. It’s amazing to watch that happen in sports, but not necessarily happen in business. It’s a confounding dichotomy for me.

There’s a joke about Larry Ellison: what’s the difference between God and Larry Ellison? The punch line is: God doesn’t think he’s Larry Ellison. If you think about that, these America’s Cup race teams threw hundreds of millions of dollars on developing a boat, and they were beat by a bunch of university students from New Zealand with a couple of millions bucks. How infuriating is that? How annoying must that be?

And again with the FIFA World Cup, New Zealand’s the only one to qualify for the group of 16. When we fielded the team, three of the players weren’t professional players, they had day jobs. If you’re a Brazilian player and you’ve beaten 150 million people to make the Brazilian squad and you get on the pitch and you talk to the New Zealand guy and ask him how he got onto the New Zealand team and he’s like, “Oh, I’m lawyer by day, but I’m just kind of good at football.” How infuriating must that be? You’ve worked your butt off to get there and these New Zealanders, we just come in and take the glory. We’re just good at everything that we try.

We definitely have it in us. How do we apply that in business? It’s demanding that high performance culture. Talent is such a key part of that. If you have talent, you have to hold them to a level of performance. You have to trust that when someone is set as a striker in your football team, and they get the ball and they have a clear chance to score, they’re not going to cake it by screwing up a basic dribble. They have to be able to do the basics well and you have to ask that of your team. I think that’s really important.

High performing teams are, in order for the culture to not be toxic, you have to have this philosophy of supporting people, not carrying them. Everybody makes a mistake every now and then, everybody has their down days, everybody has those moments. But there is a big difference between carrying someone who is just continuously under performing, versus supporting someone through a tough patch or a genuine mistake and trying to fix that. I think that’s the really key thing. At the end of the day, it’s about people.

Another key aspect is decisive leadership. It’s super important that you have really good, decisive leadership. Indecision, especially in this innovation space, and especially when you’re executing different projects, will be a killer, because there are so many unknowns.

You could spend months trying to map out the unknowns, and you could spend months trying to make a clear decision about these things. But actually, you have to use some educated data and domain expertise and try and apply yourself quickly.

I think decisive leadership is really important. Domain expertise by that leadership is really valuable, but you wouldn’t consider it essential. I’ve actually seen it done really well where you delegate that expertise, but it leads to my next point.

It’s really important that the leadership leads by example. As a young person starting a business effectively straight out of university, I didn’t know a lot about leadership. I had to feel my way through a little bit. You try on different styles, you read a book about how Steve Jobs was an A-grade a**hole and pulled off these miraculous things. And then you read about other leaders who were more consultative and you have to find your groove.

But one thing I have learned is that you have to lead by example. The one thing I stand by is I never ask anyone to do anything that I’m not willing to do myself. When someone has to work late or work a weekend, I’m there. Whether I could contribute or not, I’m there.

I’m sitting next to them and I’m making sure that they can see that because I’ve asked them to do something extraordinary in their day job, I’m going to help them be there. I’m going to sit there and just type emails or whatever. Just be present and make sure I’m not asking people to do unreasonable things.

When you do that, you imprint on people and they do that for other people. When you’re running a team of 100, it’s super important that you lead by example. People can see that that is their reference point, that’s what they’re trying to be like.

We all make mistakes, we’re leaders but we’re also human. You have to address those weaknesses and mistakes viably with the team. You can’t be beyond reproach. Especially in an innovative culture where controlled failure is actually a key part of it, where you are probably going to make a few mistakes along the way.

If you’re expecting people to perform really well and you have weaknesses, you need to also have that expectation of yourself and demonstrate it in front of people. Otherwise it’s just cheap, it’s just words.

Another key component is trust. Any high-performing team, any team that can pull off anything great, you need to be able to trust the person to your left or the person to your right. People who are set in a job, and they say “Hey, I’ve looked into something, and we’ve done everything we can, but that scenario has failed,” you need to trust that that is true.

The trust is also important for things like accountability. If you don’t trust each other, accountability quickly turns to blame. If you don’t trust each other, that decisive leadership dilutes down to weak, slow and really indecisive help. It really breaks down.

You’re never going to run a perfect game, that’s your first omision. You walk through those doors and you admit that there is going to be mistakes made, but then you have to know that at some point, trust may be broken.

And if it’s broken, you need to earn it back. You need to work your butt off to get it back because it’s so important for the rest of the game. You can’t just carry this mantle by yourself, your whole team has to buy into this and therefore you have to demand it from each other.

A key point of delivering experiences like Fast Lane, or Starship, or doing new working with Nokia on a completely unreleased early prototype device, or working with the Google Brain team on totally new machine learning software, it takes risks but they’re conscious risks. Stephen Horner, Rush’s Design Director, actually came up with the phrase “To do new things, you must take conscious risks.” I really love it because you can’t make simple mistakes, it’s not OK to make simple mistakes. Those risks are not the types of risks you need to be taking. You need to do the simple stuff, you need to do the basics as I talked about with having accountability with your team.

You have to take conscious risks, you have to say, “OK, we’ve researched this area for this new business unit that we’re developing. We think all the users are here, here’s data to support that, but it’s never been done before and no one’s really run a business model like this, so we don’t know for sure. We’re going to take a conscious risk on building the smallest possible prototype that is aimed correctly with the right vision, to test that in market.”

That’s a conscious risk, but that doesn’t mean you’re going to build a crappy app, or you’re going to not going to have a secure back end, or you’re not going to make sure that your marketing team is across it and is going to push some ad spend behind it, and your messaging is correct and it’s on brand. That’s table stakes, you’ve got to do that stuff. But those aren’t conscious risks, the conscious risk is ‘We’ve never done this before so we’re going to try it’.

How do you take these risks? How do you evaluate these conscious risks to try and do something better? If you look at this really simple diagram, this is kind of how I talk about this. In innovation or when you’re doing something totally new, you want to reduce your risks, but you want to reduce them down to one. If you reduce them down to zero risks, it means you’re not innovating. You’re not doing anything new or untested or something that everyone’s got an answer for. What I see a lot of businesses and organisations do is they think technology is the risk. But there are like 20 different things that are risky. You could have a totally new process, you could have a totally new team. You could have three or four pieces of technology that are totally new. And if you were to plot those elements of a product or an idea and you were to put them up there, you could see the average risk.

You see that blue area, that’s your surface area risk. What you want to do is reduce that surface area of risk, you want to minimise that. How do you do that? What I like to do is reduce that risk down to one thing.

If you were doing a technology project and the innovation is the technology, then sure, push the boundaries out there. But if you are doing a new business model, don’t run new technology at the same time. Try a Mechanical Turk, use people. You don’t have to use technology. Use a framework that your team knows really, really well. A really known piece of technology, you know it warts and all. It might not be the latest thing, but you know where the holes are.

Use an established team, don’t throw in a totally new team for that. Make sure that the team dynamic is already there. Get a trusted team that could be performing in some complete other area of your business, but you know that team kicks ass and they kick ass every day. So why not take a look at that team and bring them into this project to deliver that one risky thing.

What that allows you to do is, say you had $100 to manage your risk and you had three risks, that’s $33 per risk. But if you eliminate that down to one risk, you now have $100 to focus on that one risk. So you can really, really be super paranoid. You can have a back-up for the back-up for the back-up for the back-up. You can map out a few plans of action, plans are useless in flight, but the act of planning is extremely helpful for identifying blind spots and deciding how you are going to respond to things. So when you put a product out there and something goes down, you’ve got your CSR plan ready, you know how to talk to customers, you know how to calm things down, throw a voucher at it.

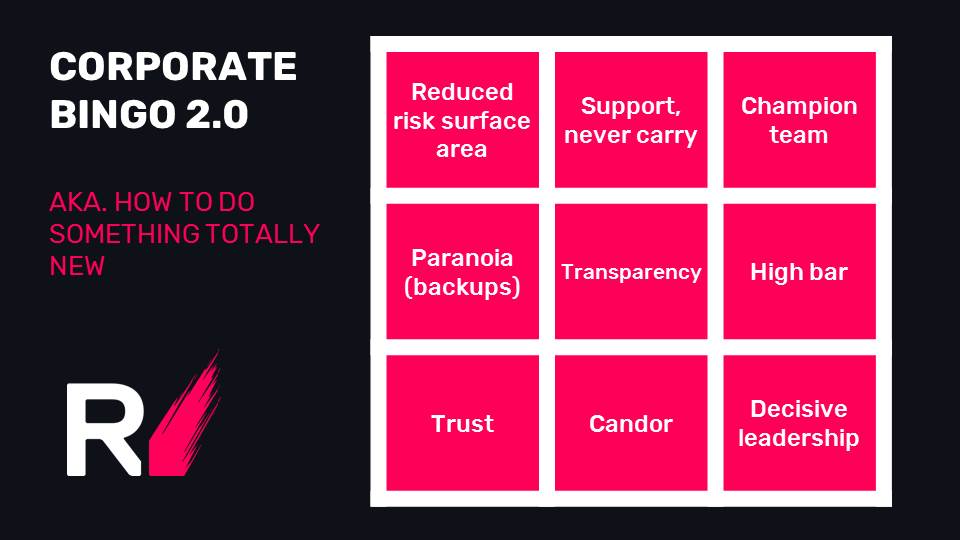

Coming back to corporate bingo, this is corporate bingo 2.0. Just recapping what I want to share with you guys, I think reducing that risk surface area is critical. Your team culture, there’s a couple of dots on there that are really related to team culture of supporting and never carrying.

Having candor. Radical candor is a phrase originating from Pixar. If you are keen for an interesting read, there’s a book called Creativity, Inc. where they talk about the story of Pixar, how Steve Jobs was involved and Ed Catmull, who founded Pixar, developed the culture there. The idea of radical candor, the ability to share and be transparent without being disrespectful. Being honest about someone’s work without being disrespectful about it is a fantastic idea.

Having that trust, setting the bar super high, that decisive leadership and then lots of paranoia. That sounds really funny, but the idea is basically understand how you might fail, focus on that reduced risk surface area and then having lots of backups and plans B’s and C’s.

Dominic Bowden: When you’re thinking about a New Zealand mindset, what is a way that you would encourage people on your team to think on a global scale?

This is an interesting area where I think diversity can actually help a lot. With diversity, you still need that decisive leadership, so that it doesn’t become design by committee. But diversity in terms of people’s life experience, it’s not necessarily about ethnicity or anything like that. As long as you’ve got a few people with different life experiences in table.

Travel is actually one thing I really rate when I’m hiring someone. Someone who has really travelled, when they can see the scale that things can be at, that opens up the mindset. There are things to do in terms of getting your team to travel. Just head over to Australia, it’s the next bar in terms of scale.

Doing an exercise on how big could this potentially be. How many people are in New Zealand, versus how many people are in these other global territories and could this idea be transplanted and what other ideas kind of look like it, or what ideas have been successful that have the same quality attributes that give you an idea that this might actually work on a global scale. I think you should always aspire to aim for two billion people in whatever you do.

When we think about now and we think about technology and how small the world has become, certainly in your space, it’s never been a better time to be from New Zealand. Certainly the global community sees New Zealand as a really innovative space, sometimes even if we don’t.

Absolutely, because it is about people and information sharing. Technology is difficult these days, the concepts are complicated. But the commoditisation of that technology is also happening at a rapid pace. 10 years ago, you could throw up a web server and get a website done, but it would take a while. But now it’s a matter of seconds to do the same sort of task to the same level of complexity. What that means is that the knowledge in your team’s head is actually where the value is and the ability to share ideas is hugely where the value is.

New Zealand has this network effect, we definitely benefit from being a relatively small cohort that is spread globally. I think there was some weird estimate, don’t quote me on this, but it’s very believable, in terms of expatriate Kiwi’s, there’s probably around 40 million around the world. So there’s 4 million in New Zealand, but another 35 million wandering around.

The network is exceptionally strong and the ability to recognise a gap in the understanding here, and look at who they can pick up the phone to and get someone in to talk about that or reflect on an idea, or hire, or all of those things. It’s pretty powerful. I think that network effect is a distinct advantage.

Find out more about our next event here