Jason Momoa’s Guide to Life

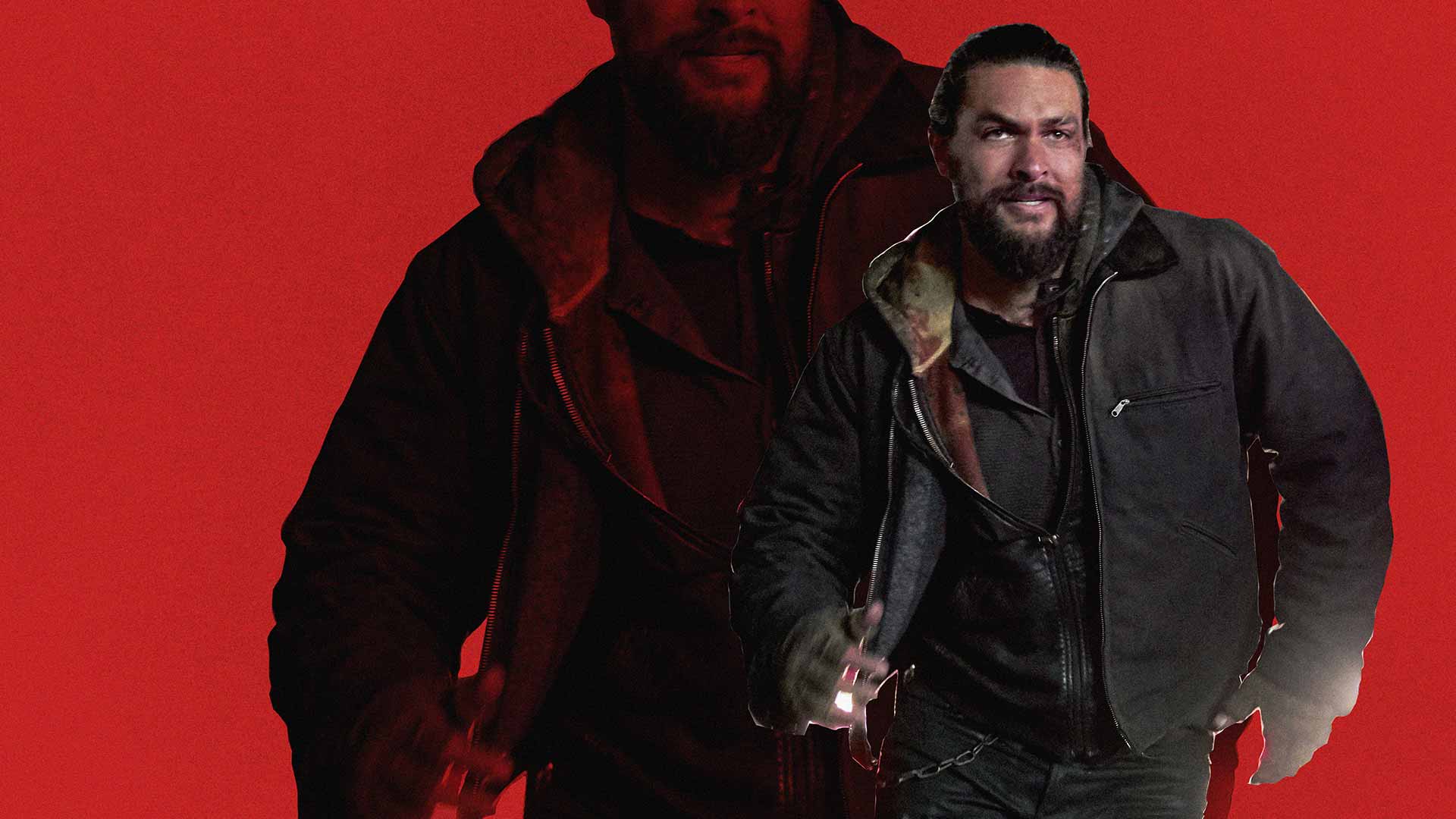

Jason Momoa doesn’t enter a room so much as change its air pressure. One moment it’s small talk and canapé maths, the next it’s a six-foot-five wall of hair, ink and laughter. On paper he’s the shorthand we all know, Baywatch, Khal Drogo, Aquaman, Dune, the blind warrior from See. In reality he’s something far more interesting: a dirtbag climber raised by a single mum in Iowa with Hawaiian roots, an art kid who built his own production company, a businessman who shaves his beard on camera to talk about plastic, and a father who insists his greatest work isn’t a film, but his children.

He’s also, increasingly, one of ours. Momoa has traced his whakapapa back to ancestral links between Hawai‘i and Aotearoa, been made an honorary citizen of Rotorua, spends his birthdays snowboarding in Queenstown, talks about wanting to live here “for the rest of my life”, and has quietly bought into the hospitality group behind some of Central Otago’s most loved bars and restaurants. On any given day you’re as likely to find him on a bike track above Arthurs Point or in a back booth at The Bunker as you are on a studio lot in LA.

This is a man who turned being typecast as “big guy with weapon” into a Trojan horse to fund his own indigenous epic, who measures wealth in time outside with his kids, who trains for the stunt not the selfie, and who treats fun as a serious strategy. This is Jason Momoa’s guide to life, a set of lessons drawn from the way he actually moves through the world, many of them now being written on our own shores.

Own Your Origin Story

“I was born in Hawaii, but I was raised in Iowa,” Momoa likes to say, usually with a grin that acknowledges the juxtaposition. In his short film Canvas of My Life for Carhartt, he narrates it over Super 8 footage of his family: born Joseph Jason Namakaeha Momoa in Honolulu in 1979, then moved to Norwalk, Iowa, after his parents split, raised there by his mother, Coni Lemke. He calls her “a strong single mother” and adds, “My mom’s an artist in every way. She’s a painter, a photographer, a wanderer, always searching, always seeing. I guess you could say my mom gave me her eyes.”

Those eyes had to learn to see two very different worlds. In Iowa he was the only mixed-race kid in town, a skater and art-room rat in a place that rarely knew what to do with either. Summers back in Hawai‘i with his father were the opposite: cousins, ocean, stories, protocol. Later, when he was asked by The Cut if he considered himself a feminist, his answer came straight out of that childhood: “I wasn’t raised by a man. I was raised by a single mother my whole life. It’d be ridiculous for me to say that I didn’t believe in it. They’re the strongest beings in the world.”

That origin story, Polynesian roots, Midwestern upbringing, an artist mother and an absent father, is exactly what gives him depth on screen. It’s why he can play a Dothraki warlord with terrifying conviction and then talk with total vulnerability about being “a product of two very opposite worlds.”

Over time, those origin threads have looped back toward New Zealand in a way that feels almost inevitable. In interviews around being made an honorary citizen of Rotorua, he talked about tracing his Hawaiian family line back nine generations and discovering ancestors who moved between Hawai‘i and Aotearoa. The fascination he’s always had with Māori culture, the haka, the ta moko–inspired ink, the reverence with which he handles pōwhiri and kapa haka performances here, are as much reconnection as admiration.

Say Yes Before You’re Ready, Then Learn Fast

Momoa’s career didn’t start with a carefully managed breakout. At nineteen he was working in a surf shop in Hawai‘i when he was spotted and pushed into modelling, then into an audition for Baywatch: Hawaii. He had no classical training, very little experience, and absolutely no business expecting the job. He said yes anyway, and suddenly he was Jason Ioane, filmed in slow-motion on beaches he’d actually grown up on.

He repeated the pattern with Game of Thrones. When he went in to audition for Khal Drogo, he didn’t deliver a safe, neutral reading. Instead, he performed a full haka in the room, drawing on the Māori culture he’d long admired. Later he told The New York Times that he’d been “fascinated with Maori culture since I was a kid,” and that he wanted Drogo to have that “very, very powerful” mix of beauty and terror he felt when he watched haka. It was a massive swing. In the wrong room, it could have ended his chances. In that room, it won him the role and changed his life.

The same “yes, then learn” instinct shows up in business. When he and his friend, designer Blaine Halvorson, started talking about vodka, they weren’t spirits industry veterans. In fact, they didn’t even like vodka. “We didn’t like vodka,” the Meili team now jokes on their site. “Vodka sucked, so we fixed it.” In interviews with Forbes and Capsule in New Zealand, they’ve described a seven-year process of experimenting with Montana spring water, grain, and glass.

Rich Is Not About The Zeroes

When Men’s Health put Momoa on the cover, the predictable questions about diet and net worth came with them. He happily talked about carbs and Guinness. The money stuff, though, he tends to reframe. There’s one line that sticks out: “We don’t own a TV. My kids are always outdoors,” he told the magazine.

He’s also been candid about the years when money and meaning weren’t aligned. In multiple interviews he’s talked about the stress of keeping a roof over his family’s head when he was still being typecast as background muscle. “I’ve led a career of having to take work to see my family, over picking and choosing,” he said in one profile, describing the period between Stargate and Thrones when roles were scarce and bills were not. There was no luxury of artistic snobbery; the mortgage had to be paid.

Now that the big roles have come, the thing that sounds most like wealth when he talks is flexibility. The ability to decline jobs that don’t sit right. The freedom to disappear to Hawai‘i or Queenstown between shoots, to take his kids on location so filming becomes an adventure rather than an absence. In his Carhartt film he says, “With them, my dreams finally came true. I’m a father. I found my place, my home… Like any father, we want our children to see us doing what we love.” The dream isn’t just the work; it’s being able to fold his children into it.

Buying into Grey Door in Queenstown is part finance, part lifestyle infrastructure. He’s now a part-owner of The Bunker, Hyde in Arrowtown and The General Kitchen & Bar at Arthurs Point, all places where he can eat, drink, hang out with friends and launch Meili or Mananalu events on his own terms. It’s money turning back into time and place. For a man who can now afford almost any toy he wants, the most consistent signal is that the richest currency he recognises is hours with his people.

Let Fatherhood Shrink Your Ego, Not Your Life

One of the most revealing things Momoa has ever said about fatherhood came in Canvas of My Life, talking over footage of his kids: “My kids are my greatest piece of art. If I can pump them full of amazing stuff and surround them with beautiful art and music, then I’m going to live out my life watching them… I want it to be the greatest thing I ever do: make good humans.” For someone who makes a living swinging tridents at a green screen, that’s an unusually grounded definition of legacy.

He’s spoken often about how becoming a father flipped a switch. In interviews he’s described his pre-kids life as “reckless and out of control,” and that once his daughter Lola was born “everything changed,” including his willingness to look after his own health. The near-drowning surfing incident off Maui that finally pushed him to quit smoking, after years of heavy habit, was filtered entirely through her: stuck under the waves, all he could think about was his three-month-old daughter on the beach. When he finally surfaced, he says, he never smoked again.

Fatherhood has also given him a strong work benchmark. Projects have to justify the time they take away from his children. Roles like Chief of War, which lets him explore his Hawaiian heritage, or Dune, which his kids can one day be proud of, make sense through that lens. So does the shift into businesses with obvious real-world impact: cleaning up plastic, creating jobs in places like Queenstown, building things they can physically visit and touch.

The ego shrink is part joke, part truth. “I’m not the king in my own house,” he told one entertainment show, laughing. “I have to wash the dishes and take out the trash and say, ‘Yes, baby.’ I’m 6-foot-5, but I kind of walk around hunched over.” The fantasy of Khal Drogo stays on screen. At home, he’s the one getting told to put his socks away.

Build A Tribe, Not A Network

Hollywood culture loves the word “network.” Momoa’s life looks a lot more like a tribe. Blood family, chosen family, creative collaborators and business partners.

In interviews he describes his production company Pride of Gypsies as “a tribe of artists and filmmakers,” and the projects he runs through it are almost always built around the same recurring faces: cinematographers he’s travelled with for years, writers like Thomas Pa’a Sibbett who share his Pacific sensibility, friends who are just as comfortable camping on a mountain as they are on a backlot.

Meili Vodka is basically what happens when you turn a long friendship into a company. He and Blaine Halvorson had been trading ideas and aesthetic obsessions for years before they decided to fix vodka. Watching them together in the early Meili press, including that launch event at Auckland’s Sky Tower, where they poured shots and traded stories, you get the sense of two mates finally bottling a conversation they’ve been having for a decade. It’s the same with Chris Sharma on The Climb and On The Roam: climbing partners first, content and commerce second.

New Zealand is now being pulled into that tribal orbit. By investing in Grey Door, he’s not just taking a punt on a hot tourism town; he’s locking in relationships with local operators, bartenders, chefs and musicians. He tours with his own band, Öof Tatatá, and drops into small venues around the country, not as a VIP guest but as an over-excited frontman. He turns up at kapa haka festivals and rugby games.

From a business perspective the underlying strategy is to build companies and projects around people you trust and actually like being around.

If The Room Feels Wrong, Build Your Own Room

There was a long stretch of Momoa’s career where the rooms he walked into didn’t know what to do with him. Castings where people assumed he didn’t speak English because of his look. Auditions where he was basically furniture. Roles where his job description might as well have been “grunt convincingly and swing sword.”

Rather than contorting himself to fit those rooms forever, he started building new ones. Pride of Gypsies was the first big statement: if the existing production structures weren’t going to prioritise the stories he cared about, indigenous epics like Chief of War, soulful road movies like Road to Paloma, or experimental series like On The Roam – then he’d make a little studio where those were the default. He’s talked about directing as the thing that finally let him “live and breathe” a project, not just clock in, take a punch, clock out.

His move into mission-driven consumer brands is another kind of room-building. Single-use plastic felt wrong, so he used his Aquaman profile and founded Mananalu to be a corner of the beverage industry that didn’t require him to be a hypocrite. Generic liquor endorsements felt wrong, so he turned years of back-and-forth with Blaine Halvorson into Meili, a brand whose aesthetic and ethics he could actually live inside.

For anyone who has ever walked into a boardroom, an industry event or a pitch meeting and felt fundamentally miscast, there’s a clear invitation: if the room keeps telling you you’re too much, or too weird, or only one thing, stop begging for space in it.

Train For The Stunt, Not The Selfie

If you’ve ever watched Momoa talk about training, one thing is obvious: he has absolutely no interest in pretending to be a wellness guru. “I grew up rock climbing,” he told Men’s Health, “and anything more physical is infinitely better than just lifting weights.” He freely admits that yoga wipes the floor with him; in one profile he said, “I tried yoga the other day, and it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. I’d rather squat a car. Climbing El Capitan would be easier than doing two hours of yoga.”

His actual training looks like preparation for an active life, not a photoshoot. Climbing sessions, jiu-jitsu, boxing, heavy conditioning, surfing, snowboarding, bike work. In multiple interviews he’s talked about preferring “anything that feels like play” to static gym work. He trains to be able to throw himself around a set for twelve hours, to do as much of his own stunt work as the insurers will allow, and to keep up with his kids when they want to charge up a hill.

“Train hard, train hard, train hard,” he once said, summing up his regime in the least influencer-friendly way possible. The important part is what comes after: train for the stunts your life actually requires, not for the validation of people you’ll never meet.

“Build A Life That Can Survive Without Wi-Fi”

For someone with one of the most recognisable faces on the internet, Momoa’s personal life is aggressively analogue. He talks about early mornings where the first thing he does is run a hill, not check a feed. “Whenever I wake up, I’m up. I don’t lie there like an idiot,” he said in one interview. “I get up, run up a hill, get some exercise, and have some time with my thoughts.”

That worldview bleeds into his choices. His homes – in Hawai‘i, Los Angeles, and increasingly in New Zealand – are base camps for physical activities as much as they are showcases. Queenstown, with its questionable mobile reception in parts and its endless outdoor options, is the perfect example. You can feel his delight in the fact that it’s a place where you can spend entire days doing things that would still be satisfying if the entire internet went down: snowboarding, climbing, biking, sitting in a bar you partly own with people you actually know.

Mananalu and Meili are digital brands in the sense that they exist on social channels, sure, but they’re designed around tangible experiences: the cold weight of an aluminium bottle instead of plastic, the feel of a recycled-glass Meili bottle in your hand, the taste of something that’s meant to be sipped around a fire rather than smashed in a nightclub. They’re logistically complex businesses built to support a simple, almost old-fashioned picture: people in real places, having real conversations.

Keep One Foot In The Dirt

In almost every profile, there’s at least one paragraph about Momoa disappearing into the desert or the bush as soon as work wraps. “I’ve spent a lot of my life living a dirtbag lifestyle,” he told Outside magazine once, a climber’s term for travelling cheap, staying dirty, and organising your entire schedule around rocks and weather.

Even at peak Aquaman fame, he’s more likely to be photographed covered in dust on a vintage bike than polished in a tux. His social channels veer from Dior campaigns to goat feeding in a single swipe. “In my man cave, I have tomahawks, throwing knives, and old black-bear furs. There’s skulls, weapons everywhere,” he told Men’s Health, half-joking about his inner twelve-year-old. The point is that he still spends a lot of his time close to the ground.

Keeping one foot in the dirt, in his case, is about more than just aesthetic. It keeps him connected to the communities he cares about, Māori, Hawaiian, working-class American, climbers, riders, and reminds him that not everything important happens under a spotlight.

Let Fun Be A Serious Strategy

If you watched Jason Momoa’s life on fast-forward, it would look like a highlight reel of pure mayhem: mosh pits at Black Sabbath’s farewell show, axe-throwing on The Ellen DeGeneres Show to raise money for charity, riding a pink motorbike through the streets of Auckland, fronting a band called Öof Tatatá at a pop-up gig in a Queenstown bar he partly owns.

But underneath the chaos is something quite deliberate: fun as a survival tool. “I’m a big wuss, and not the king in the least. My wife is,” he told Esquire once, undercutting his own Image with a capital I. He regularly calls himself “a big kid” and treats the set like an elaborate playground between takes. That isn’t immaturity; it’s a response to the actual emotional and physical toll of the work. When your job involves holding grief, rage and violence in your body for twelve hours at a time, silly string and fart jokes aren’t indulgences, they’re medicine.

The same thing drives his approach to brand activism. Shaving his hair and then his beard on camera to talk about plastic is ridiculous, and he knows it. In the original Mananalu launch video he jokes about his face and how much he hates losing the beard, then pivots straight into, “I’m here to do something that really matters… let’s get rid of single-use plastics.”

At Meili events, particularly in New Zealand, he works the room less like a brand founder and more like a mega-charismatic bartender. The Sky Tower launch coverage is basically a string of moments where he’s laughing, hugging, pouring vodka into tiny glasses and daring journalists not to enjoy it. At first glance it’s pure larrikin behaviour. Look closer and it’s clever: he’s turning a product launch into a story people will tell their friends about for years.

For leaders and founders who default to solemnity when the stakes get high, there’s a lesson here. Fun doesn’t mean you’re not serious. In the right hands, it’s how you keep going long enough to do serious things.

Own The Joke Before It Owns You

Humour is one of Momoa’s favourite tools, but he’s also had to learn the hard way that not all jokes age well. At a Game of Thrones panel during Comic-Con in 2011, he made an off-hand comment about how one of the “great things about being on the show” was that his character got to “rape beautiful women,” a line that landed with a laugh in the room and a thud years later when the clip resurfaced in the context of #MeToo. When it did, he issued a public statement calling it “a truly tasteless comment,” saying, “It is unacceptable and I sincerely apologise with a heavy heart for the words I said.” He acknowledged that sexual violence was something that had affected people he loved. It was a textbook case of owning the joke before it owned him, and of recognising that being “the fun guy” doesn’t exempt you from responsibility.

Since then, most of his humour has turned inward. He makes himself the punchline: the big tough guy who gets smoked by pensioners in yoga class; the alleged king of the sea who panics in cold water; the world-famous actor who still “has to take out the trash and say, ‘Yes, baby’” at home. That self-mockery takes the sting out of his physical presence and makes it easier for other people, especially kids, especially women, to be around him without feeling like they’re on a set.

“Am I an egotistical asshole? Ehhh, maybe,” he once joked in a profile, before going on to talk in depth about how much he still feels like “just a dumb kid from Iowa” most days. The line works because you can tell that, behind the bravado, he’s genuinely wary of turning into the kind of man his single mum would have despised.

For anyone building a public persona, whether as a founder, a CEO or an artist, the lesson is twofold. Use humour to keep your ego in check and your audience close. And when a joke reveals more about your blind spots than your wit, own it fast, apologise properly, and then do the work so you don’t repeat it.

Let Art Lead, Money Will Chase You Eventually

It’s easy to forget, now that his name is welded to billion-dollar franchises, that Jason Momoa spent a large chunk of his career being broke. In one interview with Collider, talking about directing his first feature Road to Paloma through his company Pride of Gypsies, he said, “I took no money to make art, but my woman backed me up on it and I want my children to see their father happy.”

After Baywatch and Stargate: Atlantis, he could have stayed on the safe genre-TV treadmill, playing variations of “big guy with weapon” for decades. Instead, he threw himself into passion projects that made very little commercial sense at the time: co-writing and directing Road to Paloma, shooting the Hawaiian-inflected western The Red Road, quietly building Pride of Gypsies so he could tell his own stories rather than waiting to be cast in other people’s. None of those were obvious cash-grab moves. All of them taught him how to write, to frame, to produce and to steer.

Money eventually caught up. Game of Thrones made him a cult star; Aquaman made him a global one. But if you look at the pattern, the big cheques are consistently trailing the art, not leading it. The same is true in his consumer businesses. Meili Vodka looks like a celebrity spirits play from the outside, but when Forbes profiled the brand, what came through was almost obsessive craft: a 300-million-year-old aquifer in Montana for water, a commitment to distilling only once to keep character, bottles made from 100% post-consumer recycled glass so every one is a little imperfect. At the launch he said, “I’m not only proud, but extremely excited to celebrate the launch of Meili Vodka,” and what he emphasised was sustainability and story as much as taste.

Mananalu, his aluminium-bottled water company, is even more brazenly art-first. In 2019 he shaved off his beard in a video to launch it, explaining that as Aquaman he felt ridiculous fronting plastic bottles while the ocean filled with trash. “It’s time to make a change, a change for the better, for my kids, for your kids, for the world,” he said, holding a can and urging people to switch to “water in cans, not plastic.” The lesson isn’t that money doesn’t matter; it’s that if you architect your work around the stuff that actually means something to you, the revenue has a way of catching up.