M2 Bluffer’s Guide To The Australian Open

There are two types of people in Melbourne in January and February. The ones who know exactly why Jannik Sinner’s second serve is suddenly biting harder under the lights, and the ones who nod politely and change the subject to the weather.

Photos courtesy of Rolex

This guide is for the second group.

The Australian Open is that rare sporting event that manages to be both a global powerhouse and a summer festival. It comes with its own language, its own folklore and its own rituals. If you’re going to be anywhere near a corporate box, a big screen or a bar where the tennis is on, you may as well sound like you belong there.

From wandering tournament to Happy Slam

The Australian Open is older than it looks. The first edition was played in 1905 at the Warehouseman’s Cricket Ground in Melbourne, back when tennis was starched white and the event was called the Australasian Championships rather than the Australian Open.

For decades it behaved like a travelling circus. It rotated through Australian cities and, in a detail that impresses any Kiwi in earshot, it even popped over the Tasman. Early editions were held in Christchurch and Hastings when the tournament was still a joint Australia–New Zealand venture. The “Australian” Open was not very Australian at all.

The name evolved as the tournament grew up. It became the Australian Championships in the late 1920s, then the Australian Open in 1969 when the sport finally allowed professionals and amateurs to compete together in what became known as the Open Era. That rebrand marked the moment the event stopped being a regional championship and started becoming a global one.

It took time to catch up with its ambitions. For years the Australian Open was the slightly awkward cousin of the other Grand Slams. Players complained about the travel, the timing, the facilities and the heat. Some of the biggest names skipped it entirely. That’s hard to imagine now, when the event regularly breaks the one-million-spectator mark and dominates the city for weeks.

Goodbye Kooyong

For years the tournament was held at Kooyong Lawn Tennis Club, a charming but cramped grass-court venue in suburban Melbourne. It had history and atmosphere, but it didn’t have the space or the infrastructure for a modern major.

In 1988 the Open packed its bags and moved a few kilometres down the road to a purpose-built complex that is now known as Melbourne Park. The grass went with it, but only metaphorically. On site, the lawns were replaced by a hard-court surface and a blue centre court that would become one of the most recognisable colours in sport.

The move dragged the Australian Open into the same league as Wimbledon, Roland-Garros and the US Open in terms of facilities and capacity. Bigger stadiums, more seats, better player areas and a precinct that felt like an event rather than a club.

It also changed the playing style, attracted a broader range of players and aligned the Australian Open with the surfaces of the other hard-court major in New York.

Plus, it made late-night Melbourne epics possible. Big lit stadiums, warm evenings and a city that’s quite happy to stay up too late on a work night turned the Australian Open into a very particular kind of spectacle.

Swedish star Mats Wilander sits at a hinge point in that history. He’s still the only player to have won the Australian Open on both grass and hard court, which gives you a sense of how radical that surface change really was.

Four seasons in one day

Melbourne is famous for its variable weather. The Australian Open is built around that reality. Melbourne Park is home to multiple stadiums with retractable roofs. When the heat gets savage or the rain arrives sideways, the roofs slide shut and the tennis continues in an air-conditioned bubble. The tournament runs a detailed extreme-heat policy, complete with wet-bulb temperature calculations and strict thresholds. There is an entire logistics operation devoted to making sure no one cooks on court.

This isn’t just about comfort. Those roofs, and the floodlights that come with them, are what make the modern Australian Open feel like a 24-hour event. Finals have finished after midnight. Five-set marathons have ended with both players leaning on the net at nearly 2 a.m., looking like they’ve just survived a mild natural disaster. In recent years organisers have tweaked scheduling to avoid the worst of the all-nighters, but the mythology is already baked in.

The numbers reflect the scale of what’s been built. In the last few years the Open has pushed past 900,000 visitors and then over the one-million mark across an extended three-week footprint. It’s no longer just a tennis tournament; it’s the most attended Grand Slam in world tennis and one of Melbourne’s biggest economic engines.

Enter the crown

You can’t talk about the modern Australian Open without mentioning a small green logo in the corner of almost every broadcast shot.

Rolex became the Official Timekeeper and Partner of the Australian Open in 2008. The brand was already synonymous with Wimbledon and had been linked with tennis since the late 1970s. Partnering with Melbourne completed Rolex’s clean sweep of all four Grand Slams.

On the surface that sounds like standard sponsor talk, but it genuinely shapes the way the event feels. Every tie-break countdown, every shot clock, every long pause while a player bounces the ball 20-plus times on second serve is framed by that Rolex clock on the scoreboard. When the roofs close and a match rolls deep past midnight, the stadium’s wide shot tends to include a quiet glimpse of the crown.

Rolex also backs some of the key characters in the Australian Open legacy.

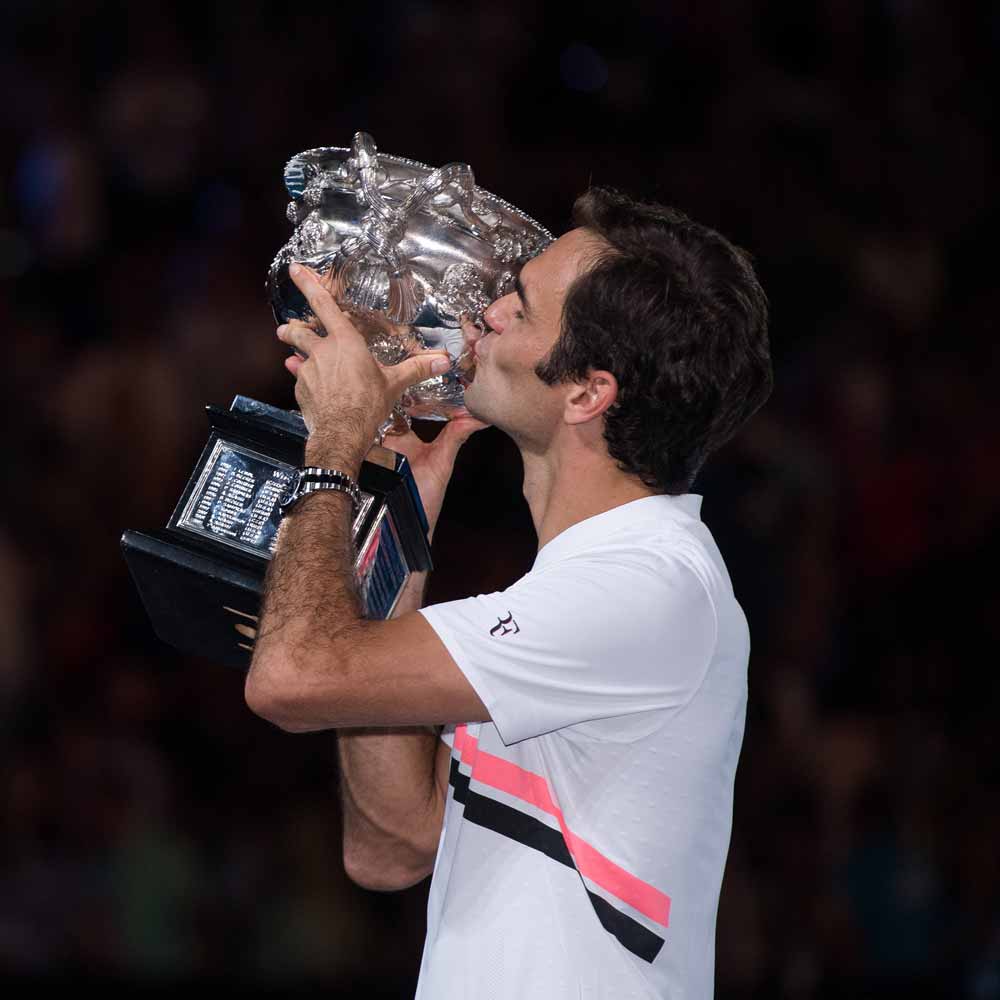

Roger Federer is the most obvious example: a long-time Rolex Testimonee and six-time Australian Open champion. His titles span generations, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2017 and 2018, and in many ways map the arc of modern Melbourne: from the early hard-court years of the mid-2000s to the fully fledged, floodlit entertainment product it is today.

Federer’s last two titles, in 2017 and 2018, came in what was supposed to be the twilight of his career. In 2017 he returned from six months off tour, beat Rafael Nadal in a five-set final and cried on Rod Laver Arena as he held his 18th major. In 2018 he defended the title and hit 20. Both moments unfolded under Rolex time, with the crown sitting quietly in the corner of almost every broadcast shot.

Today, Italian star Jannik Sinner, another Rolex Testimonee, has become the new face of Melbourne with back-to-back titles, establishing himself as the next dominant force on hard courts. For a brand that trades heavily on legacy and continuity, that passing of the baton from Federer’s era to Sinner’s couldn’t be neater.

Rolex is a sponsor, but in Melbourne it’s also part of the atmosphere. The Australian Open sells itself as a fusion of elite sport, hospitality, nightlife and tourism. The watch on the scoreboard is a quiet signal that you’re watching the very top of that pyramid.

Legends of the blue court

(and the grass before it)

You don’t need the full champions’ board committed to memory, but a few names unlock most conversations.

Start with Rod Laver. If you’re sitting in Rod Laver Arena, it helps to know who he is. Laver is the only man to have completed the calendar-year Grand Slam twice, winning all four majors in the same year in both 1962 and 1969. His 1969 Australian Open triumph, on grass, was one of the pillars of that second sweep and came in the first season of the Open Era. The stadium name is a statement, not a branding exercise.

On the women’s side, Margaret Court is the dominant historical figure at this event. She won the singles title 11 times, a record that still stands. Add in doubles and mixed and she collected more Australian Open silverware than most nations have managed.

In the modern era, the tournament has belonged to Novak Djokovic. Ten titles on Melbourne’s blue court have made the city his personal lab. The match most people reach for is the 2012 final against Rafael Nadal, a five-hour-and-53-minute slugfest that remains the longest Grand Slam final in history. By the end, both players were leaning on the net during the trophy ceremony, grinning like survivors.

But some of the most interesting texture sits around those headline acts.

Roger Federer

Federer’s Australian Open story divides neatly into two arcs.

In the mid-2000s he turned Melbourne into a personal showcase, winning the title in 2004, 2006 and 2007 and playing the kind of all-court tennis that made his game look like it had been designed in a wind tunnel. Those early Australian titles helped cement him as the dominant hard-court player of his generation.

Then came the second act. After years of Djokovic and Nadal gatekeeping the biggest prizes, Federer returned to Melbourne in 2017 after a long injury break and produced one of the most emotional runs of his career, capped by that five-set win over Nadal. He backed it up in 2018 with another title, taking his Australian Open tally to six and his Grand Slam count to 20. Melbourne became shorthand for reinvention.

Jim Courier

Before the roofs, before Sinner’s era and before the full Melbourne Park expansion, the new hard courts belonged to Jim Courier.

The American won the Australian Open back-to-back in 1992 and 1993. He came from clay-court roots but adapted perfectly to the brutal heat and high-bouncing hard courts of early-’90s Melbourne. Courier’s game wasn’t about elegance; it was heavy forehands, relentless conditioning and a willingness to grind in 40-degree heat.

His Australian Open story captures an era that feels a little wilder than today’s polished production. One enduring image is Courier celebrating by jumping, fully clothed, into the Yarra River after winning the title. In a landscape now defined by curated brand activations, there’s something disarmingly straightforward about ending the day in a very brown, very local river.

Stefan Edberg

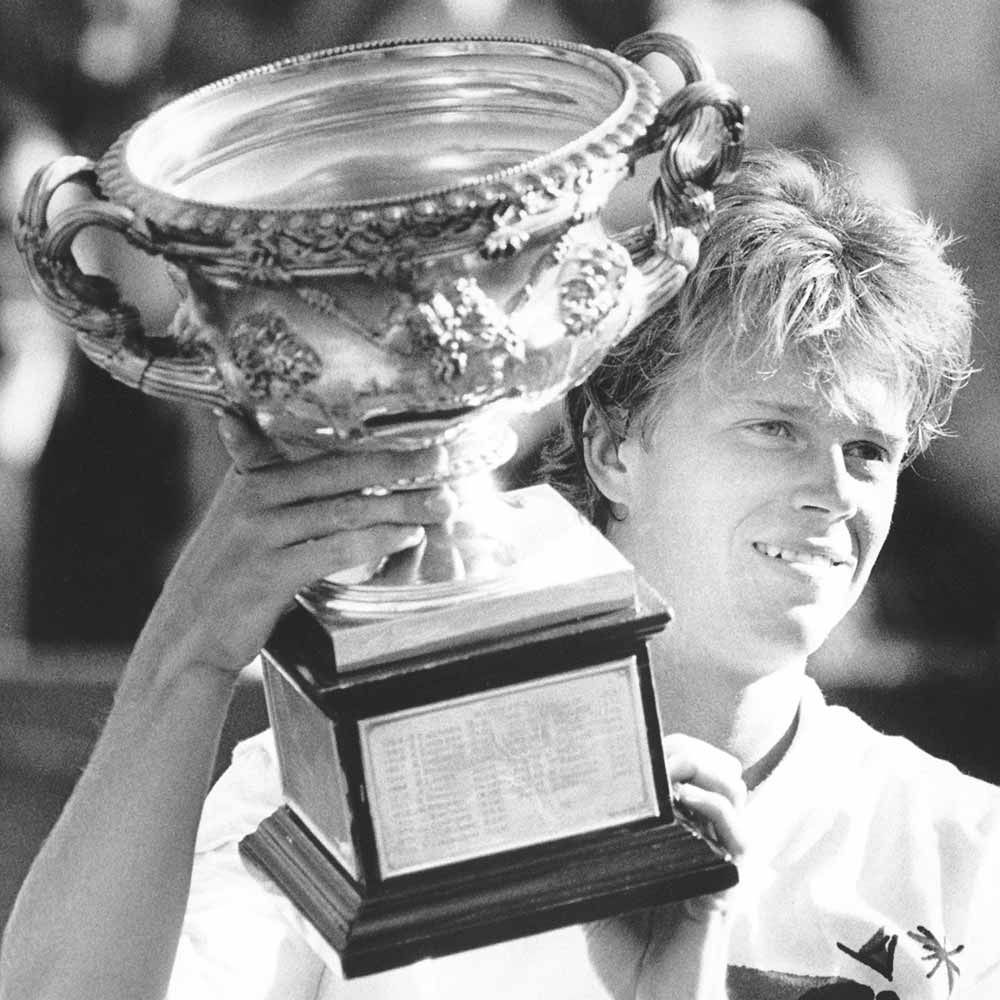

Go back a little further and you hit the Stefan Edberg chapter, the bridge between the old Kooyong days and the modern Open.

Edberg won the Australian Open twice on the Kooyong grass, in 1985 and 1987. He was the embodiment of classic serve-and-volley tennis: precise footwork, soft hands at the net and a one-handed backhand that still turns up in coaching montages.

His titles sit at a fascinating point in the tournament’s evolution. Edberg’s Australian wins are part of the last wave of pure grass-court champions here, right before the move to Melbourne Park and the hard-court era. If Federer and Djokovic are the faces of the blue court, Edberg is one of the last great faces of the green.

Serena, Barty and the modern stories

On the women’s side, Serena Williams turned the Australian Open into a personal highlight reel with seven singles titles. Her 2017 win has passed straight into tennis folklore because she later revealed she had been in the early stages of pregnancy during the tournament. In a sport obsessed with marginal gains, playing and winning a major under those circumstances almost defies belief.

For local fans, Ash Barty delivered the perfect modern home-grown story. In 2022 she became the first Australian in 44 years to win the women’s singles at her home major. The country collectively lost its mind. Then, in a twist that felt almost literary, she retired from professional tennis while still ranked number one in the world.

Most recently, the conversation has revolved around Jannik Sinner. The Italian’s first Australian Open title came in a comeback win from two sets down in the final. His second title confirmed it wasn’t a fluke. In a sport that is constantly trying to define the “next era”, Sinner’s Melbourne performances have made a convincing case that he is it.

You don’t need to know every stat or care deeply about string tension. To pass as fluent at the Australian Open, you just need to remember that it started as a wandering grass tournament, grew up on blue hard courts, made legends like Laver, Edberg, Courier, Federer, Serena, Djokovic, Barty and now Sinner, and that through the modern reinvention, Rolex has been the quiet heartbeat in the corner of the screen.

The rest is just nodding thoughtfully between serves and knowing when to say, “This feels like it’s going five.”