Making GMOs User-Friendly: The CRISPR Rebrand

Anybody know who convinced Americans that Elon Musk was the ideal auditor for government spending? Or who managed to sell Joe Rogan as a legit expert on archaeology?

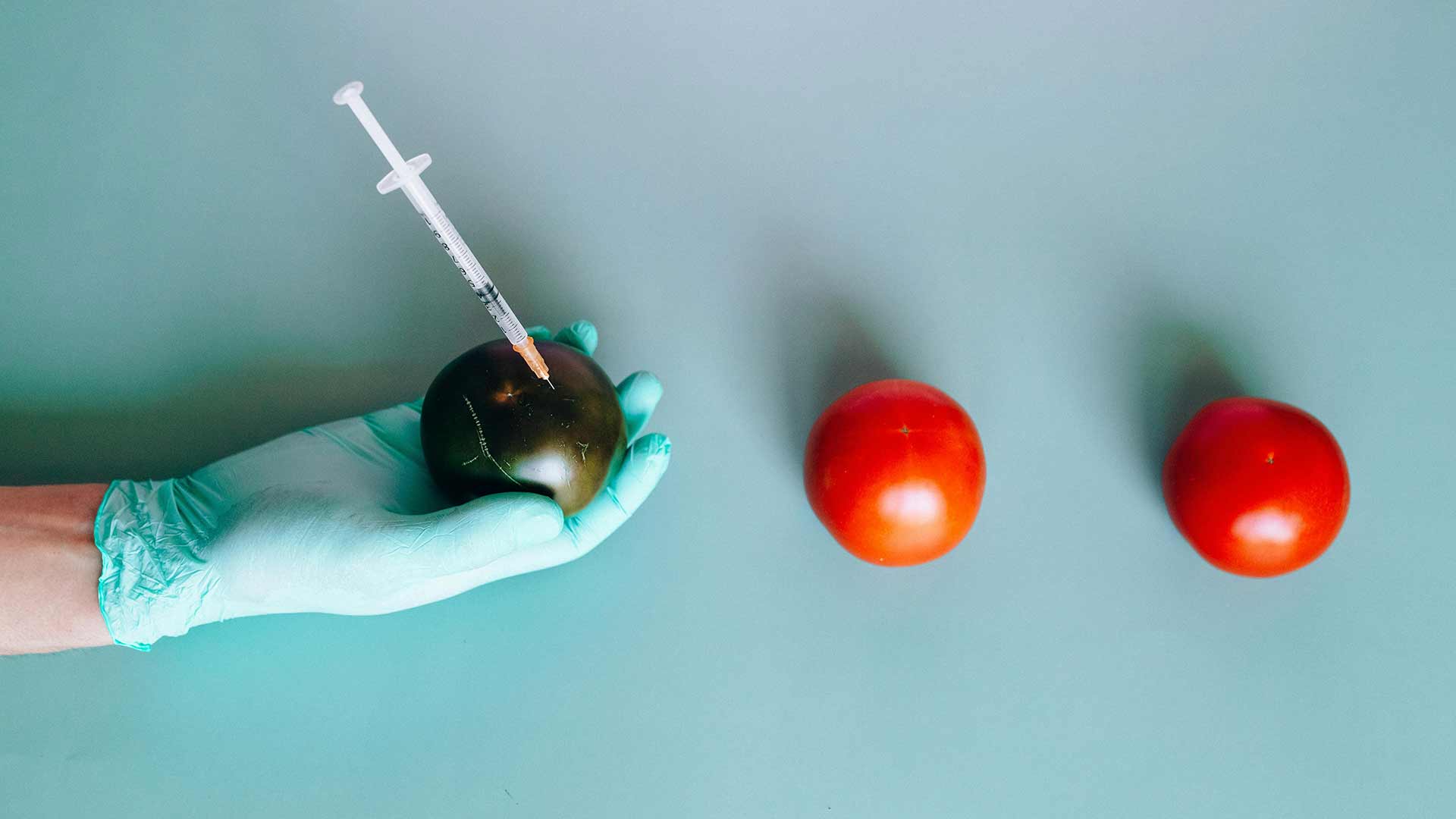

If you know these dudes, send them our way – we’ll need their help explaining why CRISPR might be more like penicillin than Frankenstein.

Gene Modding is actually old hat

We shouldn’t need them really as genetic modification has been around as long as we have. You think sheep were born docile and hornless? That carrots were originally orange? Or that bananas weren’t originally just giant seed pods?

Most people realise that much of what we consider ‘natural foods’ are actually just products of extensive human-directed genetic modification. We just get queasy when these changes happen in labs – and when they happen fast! We’ve grown so used to the idea that evolutionary change always happens at glacial Darwinian speeds, that anything quicker than over multiple generations is somehow ‘wrong’. We also used to think you couldn’t breathe if you traveled at over 35mph – now we have Formula One.

How is it so fast?

CRISPR is very fast. If you’ve ever used a word processor to edit a sentence, you can understand the concept behind it. But it’s not just the speed as other GMOs were quick too. The beauty of CRISPR is that it is just that: the editing of existing DNA to improve it – or remove weak or disease-susceptible traits. Unlike many of its unpopular/discredited predecessors, simple CRISPR does NOT involve inserting foreign DNA. It makes the end product look indistinguishable from one produced much, much slower via natural mutation or traditional breeding programs.

How about in the Real World?

Let’s look at how CRISPR could have changed the game in a real world scenario:

Remember Zespri Gold? You know, that golden kiwifruit that came out in the late 90s? No, not the Sungold you find in the supermarkets now, that’s its replacement.

Today’s Sungold (Zesy002) is similar to the old Zespri Gold (Hort16A) but not exactly the same. It only came about because it turned out Zespri Gold was ultra susceptible to PSA (Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae), a bacteria which more or less wiped it out in the orchards. Damn! It was so yummy too!

Zesy002/Sungold was chosen as its replacement as it was less susceptible to PSA. Luckily for us, Sungold is super yummy too, so we haven’t lost anything in the trade off. This time…

Because PSA hammered Zespri Gold 20 odd years ago, Zespri had to go the long way around in fixing their problem. They had to screen thousands of natural mutations over years to find a suitable-tasting replacement that also could also stand up to PSA. Luckily they managed to find one in Sungold that ticked all the boxes. Whew!

Today of course we have a much quicker solution in the wings in the form of CRISPR. Potentially one snip of Zespri Gold’s genes, one tweak and that delicious original golden flesh would be firm, shippable and PSA-proof. No long search for a replacement, no gamble on whether consumers would accept it, no wait time for the problem to be solved.

Can we use CRISPR here?

Not yet. Here in New Zealand, gene-editing still technically counts as genetic modification. Ie CRISPR is still lumped in with all those horrendous Frankenfood techniques like transgenics (eg; putting frog genes in sunflowers), gene drives (eg; playing God with mosquitoes’ reproductive abilities) and IP stacking (eg; Monsanto engineered herbicide resistance/pest resistance/drought tolerance ‘Buy from us or else!’)

The only reason CRISPR is currently lumped in with the axis of evil is because the Law moves a heck of a lot slower than Science these days. As CRISPR is a relatively new technology – newer than the current Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 anyway – it has been classed as a genetically modified organism (GMO).

The good news is; there’s legislation in parliament now aimed at rectifying this. The Gene Technology Bill 2024 aims to establish a modern regulatory framework for gene technology by implementing risk-proportionate regulation and – most importantly – to align us with international standards for trade and tech advancements.

This new bill will move us to a position similar to the worldwide trend of allowing CRISPR-style gene edits (with no introduced foreign DNA) particularly if they show ‘null segregants’ – or no foreign DNA remaining in the edited organism or its descendants. The logic behind it is sensible; if the genetic change could theoretically have happened in nature – it’s okay.

Aren’t we just rewriting the fine print?

Yep, largely because the syllables ‘genetically modified’ have such a bad rep. The public has been burnt before with all sorts of things including Mad Cow Disease, chlorine-washed chicken and whatever that stuff is the Americans call ‘Food’. But there’s a growing awareness around the world that CRISPR is actually really cool and the Zespri Gold case is a classic situation where it could have made a huge difference in costs and time. Heck! It would even have allowed the consumers to still keep the exact product they fell in love with in the first place.

So CRISPR hasn’t changed to meet the new legislation, instead we are starting to change our attitudes to genetic modification enough to allow it into our lives. Should this bill pass it will shepherd CRISPR out of the radioactive Monsanto doghouse and into the same green fields paddocks as selective breeding, beer brewing and hybridisation. It’ll soon be just another tool in the biotech toolbox — freeing up our best spin doctors to focus on the real crisis: helping Mark Zuckerberg prove that the metaverse wasn’t a very expensive hallucination.