Re-writing Trauma

The brain-child of UK-based author Georgie Codd, BookBound 2020 was the first of its kind. It took the big names and thrills of a normal literary event and used an online platform to offer a bit of light to book lovers during daunting lockdown times. The festival took place at the end of April on YouTube and offered a wealth of well-known names, like Bafta-winner, Robert Webb, Man Booker Prize nominated, Max Porter, and novelist/playwright, Alex Wheatle amongst many others. Kiwi writers flew our flag too, such as, Becky Manawatu, Renée, Pip Adam and M2 magazine staff writer, Jamie Trower.

In partnership with UK literary magazine, Wasafiri, BookBound 2020 also aimed at raising money for the UK-based mental health charity, Mind, and the NZ-based, Changing Minds, who both provide advice and support to empower people experiencing mental health problems.

As the events occupied our computer screens for seven days, we would be remiss not to acknowledge the power and performance of each of the pairings. The events sparked with such life and insight. A definite highlight in the festival programme was watching our own Jamie Trower chair the talk between award-winning authors, Uruguayan Daniel Mella and American novelist, Winnie M Li. Their conversation, entitled ‘Real Life Fiction’, allowed the three writers to talk openly and honestly about how traumatic experiences shaped their writing.

Daniel Mella is one of the key figures in contemporary Latin American literature. He published his first novel at age 21 and has been awarded highly for each of his works. Winning the Bartolomé Hidalgo Award and gaining international acclaim earned him the status of a cult writer. His latest book, Older Brother, is considered by critics to be the ‘Dostoyevsky of the River Plate’ and is based around the tragic death of Mella’s brother.

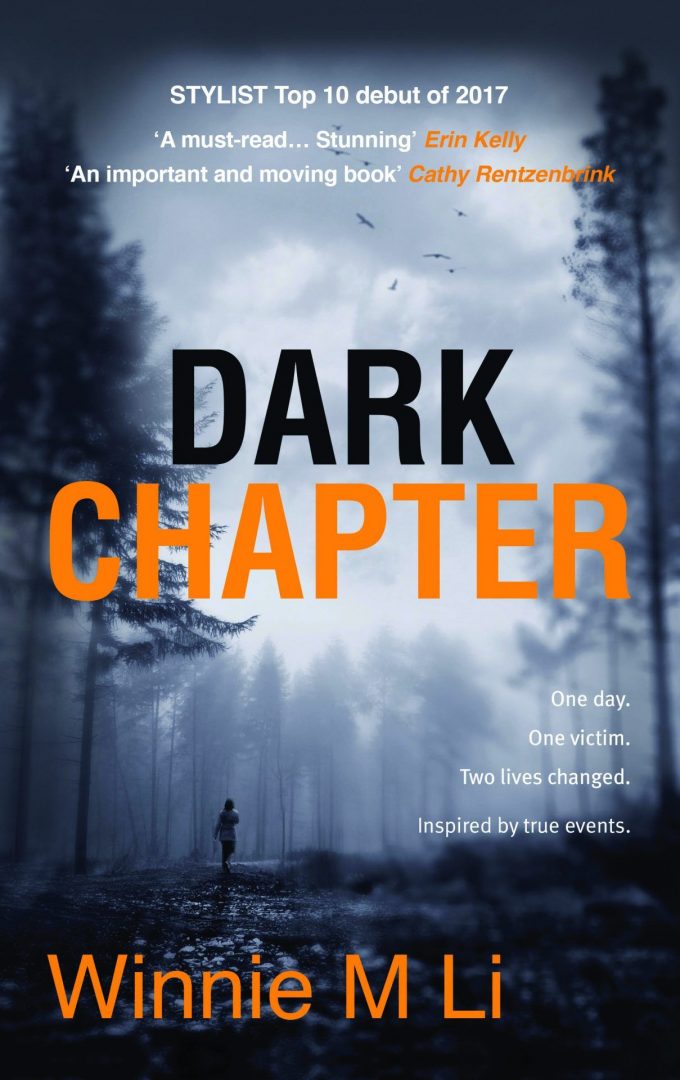

Winnie M Li is a London-based American writer, novelist and activist. Winnie’s first novel, Dark Chapter, was released in 2017 and is based on Li’s tragic real-life rape. The book won The Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize, was nominated for the Edgar Award and shortlisted for the Authors Club Best First Novel Award. The book has been translated into 10 languages and has been highly praised as being ‘brave’, ‘raw’, ‘powerful’, and ‘a must read’.

JAMIE TROWER: I’m thinking of starting this discussion off with a quote from Daniel’s book. On page 35, you talk about conversations you would have with your father on survival. “Survival”, you write, “the inhalation of the human race and the stupidity of the human species”. I also liked how Marcos, on page 37, quite poetically I think, explains how “dolphins can choose to stop breathing”, a very animal trait for us humans. From that, I feel, trauma victims like us, we sit on an axis of surrender and survival. So as humans, as artists, as activists, as writers, how would you say that you both survive?

DANIEL MELLA: You made me think of this last month – everybody’s attention seems to be on survival. I’ve been thinking about it a lot because it seems like when we’re very worried about survival and that’s our main concern, the possibilities of doing something beautiful diminish greatly. I think that one of the things that I’ve maybe gotten from writing is precisely that.

When you’re writing and when you’re feeling good about what you’re writing and you’re in that trance-like state of creating a book and living with a book, survival recedes to a second or third-degree of importance. I think that’s when you can do your best work. That’s also what pains me when I look around and see so many people worrying about survival. It seems like all the possibilities for really doing something worthwhile or beautiful or creative just get lost. I think that the worry for survival is a very difficult trick to come out of.

WINNIE M LI: It’s that hierarchy of needs – Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Of food, shelter, some would say sex. All that stuff is at the bottom and you need to be able to have that before you’re able to have livelihoods and are able to support art. I think, in lockdown, in some ways it’s the ideal situation for a writer to be creating art. We think, ‘We’re shut indoors and we’re just trying to write books because there’s nothing else to do.’

I guess there is so much anxiety about what’s happening in the world right now. I’ve been ill for about six weeks with what’s probably a mild version of Covid, but it’s been ongoing and annoying. You think about people that have it, probably much worse than me. People have relatives, or themselves, on the brink of survival and there’s no space in that kind of situation to be able to write or to create art. I think it’s hard to pursue the arts at the moment. There’s so much precarity around you.

In terms of your question, Jamie, I interpreted it like survival means different things at different points along the journey. So for me, Dark Chapter, is a fictional retelling of my own rape, which happened in real life. When being assaulted, there is very much a question of survival. That kind of fight or flight mechanism kicks in and it is very much, ‘Am I actually going to survive this assault?’ That’s one form of survival, and a part of the brain kicks in where it automatically does stuff that enables you to survive somehow.

That was kind of a survival event for me, during the immediate moments of the assault but then the weeks and months after that, it’s a different kind of survival. Your life actually isn’t being threatened in the nine months or the ten months or the two years after the assault. But you’re kind of being forced to relive it because of PTSD. That’s a different kind of survival you somehow have to survive. This ongoing, repeated trauma. Your memory doesn’t let go of it.

I think that is survival in a different way. You have to confront that trauma and some people do through art, through writing, through therapy, who knows. That’s a different form of survival in terms of how you live day to day, when you’re not actually afraid of dying.

DM: Winnie, do you feel that writing the book helped you survive?

WML: No, because I didn’t start writing the book until five years after the assault so I had this long period after the assault of the legal situation. Then just having really bad PTSD and depression and anxiety and I had to figure out how to rebuild my life. It was only until I got to a point where I had a new job and was financially secure again that I was able to write the book as the novel.

That goes back to the hierarchy of needs because it was when I no longer was actually afraid for my own life, when I was no longer being chased by those memories. I had a new place, earned decent money – that’s when I felt secure enough as a human to pursue the writing itself.

I’m curious, Daniel, about how soon after your brother’s death were you able to start writing [Older Brother] or approaching it the way that you did as a writer?

DM: At the beginning I was just writing down feelings but in a very chaotic way. I wasn’t writing a book or anything. I always found writing to be a way in which I could think better and even feel more clearly. I know where I am. But then six months after the death of my brother, it just sort of came to me. I remember the morning when my brother had died we were sitting with my mother on the porch, like in the first scene of the book, and my mother said, ‘Why did your brother have to die when he was such a happy person? When there’s other people who keep bitching about life and complaining and only see the bad side?’

I didn’t answer anything that morning, but when I remembered it six months later I said, ‘What would have happened if I had said, “Oh, you’re right, it should have been me”?’ That’s when I realised that was something I hadn’t said. A feeling of guilt that I was actually carrying inside but couldn’t admit to myself.

So by writing what hadn’t happened, by allowing what I hadn’t said to be said on the piece of paper, then I had a book – then I had a structure. I had an opening to my own true feelings. I could start actually making a fiction out of it because the narrator was saying something I didn’t say. In a way it’s a lie, it’s fiction. That’s basically the mechanism that allowed me a way of coping with it. Like coping with the sadness, or the grief.

JT: Why fiction? Why not memoir? Why not nonfiction?

WML: Like I said before, I had five years between the assault and starting to write, so during those five years I had a lot of time to think about sexual assault, sexual violence, and know why it happened. It was certainly one of those things that I never expected to have happen to me in my life, but then it did.

For those who haven’t read my book, I was out in a park in the middle of the day, and I was followed by a stranger who raped and assaulted me violently. It was one of those really random occurrences, as random as lightning striking. It’s the randomness of the occurrence that changes your life fundamentally. I couldn’t really make sense of it.

So I took a while to just deal with therapy, and recovery. I started reading a lot of memoirs by other rape survivors because, again, I couldn’t really make sense of it. Suddenly I turned to books, and there are a number of really great memoirs. ‘Lucky’ by Alice Seabold and ‘After Silence’ by Nancy Venable Raine. Those memoirs are very powerful. They are very much about surviving the rape in the aftermath, so I’ve read a number of memoirs. I felt like that had already been done, like other writers who’ve written really good memoirs about surviving a rape in the aftermath and I wanted to do something new, so that’s why I wrote it as fiction.

The key to trying to make sense of the whole strangeness of it was trying to understand why my perpetrator had done it. I’m never going to know it too because he’s a stranger. He was a 15 year-old boy at the time that he assaulted me, so automatically there were a whole bunch of questions. What happened to that boy in his 15 years of living that had caused him to be so violent? What made him think he could just do that to a stranger he saw in the park?

So I wanted to write this fiction so I could imagine the rape and everything that came before and everything that came after through his point of view. I knew, obviously, I couldn’t do that as a memoir; you can’t do that as nonfiction. Fiction allowed me a certain kind of freedom as an artist to take this horrible thing that happened to me and transform it into something more productive. It gave me some more mastery over a situation where the very definition of sexual assault, sexual violence, is that you have no control over it. Suddenly I had control over it. I had control over a character who was my perpetrator, so it was a strange kind of puppetry I suppose.

For me I wanted a creative challenge to turning fiction. If I had done it as a straight memoir I think it would have been interesting but probably too sad. I would have just been writing from my own perspective, and I wanted to at least be able to construct another character without being forced to relive it. It wasn’t just my own experience, it was something new, it was kind of more unexplored territory for me.

DM: From the get-go I had that image, that memory, which I perverted and changed. From the beginning I knew it was going to be laid out as a fictional account and maybe the fiction is not necessarily making up stuff but just taking something out of context, something that actually happened but making somebody else do it – something somebody said. So it’s just moving pieces around that makes it a fictional account.

The compression of time. There’s a lot of things I make happen in a couple of days that actually maybe happened in a span of a year and a half or two years, and I thought that gave me an actual freedom. If it was going to be nonfiction, I would have had to be faithful to the events and to the people involved, but the novel starts having its own demands and giving you its own structure. I’m telling you where to go. It’s very easy to start discarding the things that you should have said if it was going to be a non-fictional account because you have to be faithful to the actual event. If it’s a novel, then what doesn’t fit in there and that structure just falls off and it’s not necessary.

I felt like it was a blessing for it to come as novel because it gave me the actual shape. The form in which I could tell that story because if not, I think I would have maybe spent years and years filling pages and pages. There’s so many things to say. But I think the knowledge structured it and gave me a firm ground where to stand on and to feel more stable, more secure.

WML: You have more freedom and there’s less with nonfiction. There’s a certain accountability to people that are alive and you have to be ethical as well. With fiction, you need to do what you want in some ways and just say. You don’t have to feel like you’re representing things as they actually happen. Quite a lot of the things that happened in Dark Chapter are based on real-life events. Everything that happened to Vivian, for the most part, happened to me, but I rearranged the order because it has a more dramatic impact if events unfold in a certain order. Some characters I conflated in two.

The one thing that I completely created was the court scene. There’s a trial which happens where the perpetrator is on trial for the rape and that didn’t happen in real life because in real life, my perpetrator pleaded guilty. Narratively that kind of falls flat if you have a crime that happens and then this kind of chase afterwards where they’re trying to find a criminal and then they find the criminal and he pleads guilty – it’s not as narratively satisfying. Readers want a big showdown to take place. I created the court case and I just imagined how it would have been.

If I was writing nonfiction, I couldn’t have done that to satisfy a narrative. That’s why I decided to use fiction, because you owe it on some hand, if you’re writing about real life, to reflect the reality of what happened. If you’re using fiction and you also owe your readers to have a satisfying read in some ways or to have something that fits our expectations of narrative a bit better.

DM: I thought it was really impressive how in Dark Chapter you managed to speak from the point of view of the rapist and how you were able to make him into a real-life living breathing character. He’s not just some archetypal criminal. He is his own person. That blew my mind because what kind of imaginative effort and emotional investment do you have to make in order to make the perpetrator a real person. You’re in a page; it takes emotion, it takes some really brave commitment to the craft.

I was wondering what that experience was like for you because you could have made him into a cardboard character, two-dimensional?

WML: It kind of speaks to what you know. #Metoo! The stories coming out about sexual violence. For the longest time, we’ve had a tendency to think that the things they do are monstrous. There’s a tendency to think they’re these monsters who live on the other side of this wall of humanity. Rape is committed by a number of people you know. We probably actually know people who have committed it, but nobody actually confesses it, right?

It’s a very widespread crime. Any form of criminal is a three-dimensional human-being, so I think there’s a tendency to automatically want to make the rapist that shadowy figure in the bushes who breathes hard in a movie. My vision for the book was to tell the story of a rape equally from the point of view of the victim and the perpetrator. I knew my experience really well, obviously, so I didn’t have to do any research there. But for me the book wasn’t going to work if half the stories were told by a cardboard figure or something who’s like a stock villain, so I had to make him three-dimensional and the key was that he was so young. If he had been my age, I might not have even been interested enough in a story to try to create him as a character. Because he was a 15 year-old boy, lots of questions about what his life had been like, there is a certain sadness to it.

I think when you’re dealing with any story of violence, there’s a sadness at the heart of it. But what drives somebody to be that violent? I don’t know personally, but there is grief and that violence has to take root in something.

For me, I wanted to try to imagine a young boy who maybe hadn’t had a great life and that maybe he’d witnessed some forms of violence that had led him to committing the kind of violence he did. Obviously, he had certain ideas about women, girls, as well as the kind of misogyny that pervades our society, or certain kinds of societies. The key is trying to make him human. Imagine him being quite vulnerable himself so it was important for me to imagine what he was like at two years old and pretty innocent. How did he learn these kinds of attitudes towards women?

There’s a sense he’s been betrayed by his family and by his community as well. I had to give it a sense of humour. It does take a certain amount of commitment, but it was actually just more interesting creatively being so different from my own experience. I live in a nice world, educated. I don’t encounter people that have had particularly bad childhoods. I like, in some ways, that it was more interesting for me than retelling the story of my own life really. It did take a lot of commitment and I’m not doing it in my next novel.

JT: Daniel, I’m quite interested in how you travelled through your narrative in the different use of tense. You mixed up the forms of time, making a trauma that was a future occurrence, inching itself to happen and also presently occurring so it’s a cloud of grief. Was there any specific reason for doing that?

DM: At the very beginning, it was a very simple reason. I was getting a little tired and bored of the whole text. I was writing it all in the past tense. So I was like “what can I do about this?” I put some things in the present and others in the past but then it was still really hard to grind through it. It just came to me. I remembered a scene in which my father went to pick up my brother’s body and they were keeping him in the police station of the beach resort where he died.

My father had been in that police station when he was young in that same building so he had a flashback of himself as a young man in that place, and now his young son was dead in that same place he’d been there 40 years before.

I thought of how time just collapses in these moments of trauma, and these moments where something unexpected like that happens. I started realising that maybe it was the perfect strategy to demonstrate it. To show that suddenly we had entered a kind of vortex where time was just gone awry, and there was chaos of past, present, future.

At the beginning I wasn’t sure it was going to work, but the more I wrote in that way, the more it started making sense. I didn’t know what I was doing. That’s what I loved about it at the beginning. I didn’t know why I was doing that. I was just bored and I want to switch it up a little bit and then it started revealing itself with the meaning it had. I didn’t have access to it logically to begin with.

WML: You do that again quite beautifully at the end, [Daniel]. At the very end of your book there’s this tree that you describe and you’re kind of mixing up the present. Then in the wake of that, you’re walking your two sons towards this tree. You’re intertwining that with your own memories of you and your brother playing on that tree. I thought that was done quite beautifully because you’re moving.

Your book is about family and the circularity of generation and those generations overlapping upon each other. Brotherhood and fatherhood and all that. The way that you mix up tenses and also kind of intertwined past and present, and memory, and what’s happening in a moment.

DM: I’m glad you liked it. I thought people weren’t going to understand anything. At the beginning, I thought this is some silly trick I was trying to play on people. I’m happy to see that it actually worked. It makes me trust the writing process, because you discover stuff as you write. You discover the shape of what you’re writing because it is revealed while you are writing it. I think that’s maybe one of the things that this book confirmed and taught me again. To trust the writing process and let it tell you what to do and think about it later after you’ve given strategies that surge of chance.

WML: Trust your readers. If you follow third-person convention and past tense. Dark Chapter is written in the present tense. I started writing in the past tense and then I wanted to make it present tense. I wanted it to feel more immediate and at one point I slipped into first person around the time of the assault, and then back out. Trust that the reader will still understand what’s happening, or even if I get a little bit confused, it’s more about the atmosphere that writing in a different tense creates.

JT: Winnie, do you think there has been a difference in regards to the reading and reception of Dark Chapter since it was first published to now, in regards to the bigger discussion in society surrounding sexual assault?

JT: Winnie, do you think there has been a difference in regards to the reading and reception of Dark Chapter since it was first published to now, in regards to the bigger discussion in society surrounding sexual assault?

WML: There’s definitely a bigger discussion happening. With Dark Chapter, the British edition came out in June of 2017 and then the US edition, which was released by quite a small press, was released. That came out in September of 2017, then the Weinstein allegations came to light in October. The American edition coincided with the Weinstein allegations. It was lucky. If the book came out two years prior, it may not have gotten as much attention. I probably would have gotten a bigger deal. From a publishing/industry perspective, we struggled. They said it represented sexual violence, which in some ways is ridiculous because you know what happens.

It’s a trauma that happens to a lot of people. It’s important to tell that trauma honestly and openly. When people tell me [the book has] helped to open up a wider conversation about it, I guess it’s not the only thing that there is. There are lots of other books out there and obviously there’s all the people that came and told their stories about Weinstein and Bill Cosby and a number of other figures.

What’s been really interesting is to have the book come out around the time of #MeToo. It’s no longer the big hashtag in the media anymore because people are caring more about Coronavirus. These issues of patriarchy and gender-based violence continue to this day. Probably during lockdown they’re even worse. People have said it’s changed their understanding of sexual violence.

The rape is one of those things where you don’t ever really think it’s going to happen to you and then it does happen to you and then all those stories you’ve heard before don’t prepare you for it. People that haven’t had that experience have read it and said, ‘It’s given me a better understanding of what my sister went through at the time.’ Certainly, I’ve had men that have thought twice about how to speak to a woman or a woman’s fear that they are going down a dark alleyway at night. It’s something a lot of men don’t feel so often.

Being able to bring that fear and that kind of anxiety to life a bit and allow male readers to get into that experience. The conversation has definitely opened up. I’m hoping that, with Covid-19 and the lockdown, we’re not going to forget about those issues.

It continues to be a problem for a lot of women around the world, but men are also in the equation. They can be victims as well. Yes, they’re also frequently the perpetrators. There’s a whole cycle of culpability and accountability that needs to be constantly brought into question. I hope with literature and movies out there, that the conversation can persist.

Sorry that was a very PR answer!

JT: Don’t apologise! It was a good answer! It’s a big topic and it’s a big problem around the world.

WML: It had its day in the media. I hope two years from now, Covid-19 isn’t going to be the big hashtag. Will people still be thinking about issues of #MeToo or will we have had a regression? As long as people keep on reading and talking about it I think that’s one way it will keep working.

JT: What have you both used to heal since your traumas?

WML: I’d say time. I guess that time happens.

JT: Time is everywhere.

WML: There’s that phrase which may be a bit cliche: that time heals all wounds. It kind of does in some ways, obviously traumas, like sexual violence, can be recurring and can occur when you least expect it. Things happen in the intervening time. I guess after my assaults, part of me just wanted to do as many things as I could, despite the PTSD, that put more space between the trauma and my current point in life.

I was doing all this traveling here after my assaults, which was a bit nuts looking back on it now, but I was just trying to create more memories and more positive things. I guess time allows you to experience other things and with the experience of other things that makes the trauma end. It recedes into the distance a little bit.

Interview between Daniel Mella and Winnie M Li by Jamie Trower. Used with permission from BookBound 2020, the world’s first online ‘antiviral’ literary festival. All interviews are available to view on the BookBound 2020 YouTube channel. You can find out more about BookBound 2020, Wasafiri, Mind, and each of the authors, by visiting their website: bookbound2020.co.uk