Split Enz: Repercussions of Greatness

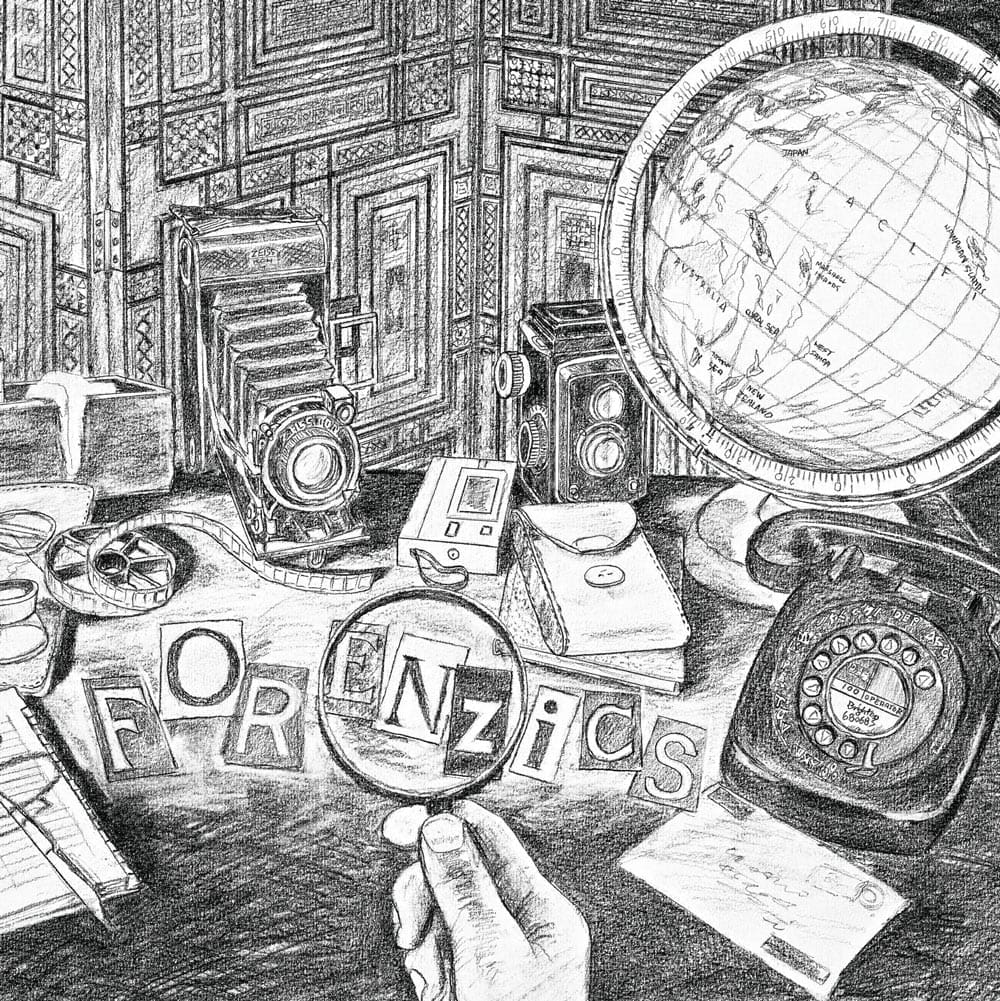

Something profound happened to the history of New Zealand music when, through some divine planetary alignment and the drive, talent and vision of Tim Finn, we got Split Enz. With hit album after hit album during the 70s and 80s, the band produced a library of iconic songs that are as meaningful today as when they were released. And while no Spotify playlist, album collection or even CD stacker is complete without a good dose of Split Enz, make room because Tim Finn and former Split Enz bandmate, Eddie Rayner, are back with a new project, Forenzics, and a new album, Shades and Echoes.

As the name suggests, the album has been an opportunity for Tim and Eddie to revisit their early work to find inspiration, motifs and elements to form new songs. The resulting album brings with it a sense of the gravity of its past but never feels constrained by it and you get this palpable sense that Tim and Eddie took the momentum and the elements of what came before, but then turned their attention to the future and creating something very new.

Tim Finn shares his “work from home” process behind this album, the drive that comes from belief in yourself and the power of a little bit of naivety sometimes.

What does it feel like when you’ve put the album out and now you’re waiting on that feedback or that sense of how it’s sitting?

We started it in 2018. There was a nice, slow natural process to it. We didn’t rush it. We were able to sit back and reflect for a few months and then try some other things. So here we are, finally putting it out and it’s an exciting time.

It’s also a time when you have to make videos and get the visual content up. You’re thinking about ways of waving a flag for this music and being noticed. There’s a lot of stuff going on, a lot of stuff out there, so it’s hard to be heard or listened to, but at the same time, we’ve got a track record. We’ve got fans we hope to key back into, through the Split Enz history.

I think there’s a lot of enjoyment in the record for fans of the very early stuff from the seventies, little key motifs here and there, that just seem to weave quite naturally into the music we were writing. It’s one for the fans and we hope it spreads from there.

You mentioned before when you’re putting stuff out there that there is a lot of noise, what do you mean by that?

I really just meant music in terms of never before in history have so many people been making music and having it be publicly available. Throughout history, mankind has always made music. We grew up with music in the house, my brother, Neil, and I. If there was a party, there’d be somebody on the piano, music would be live. So we grew up thinking that that was just a natural part of life and it is.

But nowadays, to go from there to becoming a professional musician to make it your life was a big leap coming from Te Awamutu especially. I’d never met any musicians, I didn’t know any, no one in our family had ever done that. It seemed like a huge leap, although I took it willingly and with great abandon.

When I was 19 or 20 and we started Split Enz, it was an irresistible force. I didn’t have any choice in the matter, that was my life. That was my future. I didn’t realise how difficult it was going to be to find an audience.

But these days, that leap of faith is much smaller, it’s just a step really. There are programs in schools, there are many opportunities for young people to feel like, ‘I could write a song and maybe I can do this’. And they record it at home and it sounds just about as good as the real thing. Then it goes up and sure, nobody might listen or pay attention, but you might get noticed and you might get a record deal out of it.

All those sorts of things now have changed the whole thing. There’s just a huge amount of stuff out there. Eddie and I have a history together in Split Enz. We’re lucky because at least a fairly good number of people know about us. But it still means you have to penetrate that.

Growing up in Te Awamutu, it just seems like such a juxtaposition to the world that you had gone into. Where do you think it came from? Was it a bolt of inspiration that came down upon you to show you what you could do?

For me, it came very much from meeting Phil Judd particularly, but also Noel Crombie and Rob Gillies. These guys were going to Elim Art school. They had probably from their early teenage years, thought of themselves as artists and never questioned it. I’d never met people like that. These to me were the real deal. These were the people I wanted to hang out with. I was fascinated by them.

I just got drawn into that world, but when I left university in 1972, I didn’t know what I was going to do and that lasted for several months. But I had these friends who were making art and who were just really interesting to talk with, to hang out with, to have fun with, and then gradually came to play music with.

Phil Judd and I started playing acoustic guitars together in 1972. That night we’d written two songs, which became our first single and that was it, our destiny was written. We just followed that through.

It was meeting those people and they inspired me to imagine that I could have a life in that world too. Having said that, I did write songs at school, I was always forming bands, but never thinking for a moment that that would be my life in music.

You’ve previously spoke about this New Zealand apathy of local. Do you think that has shifted?

New Zealand is only really recognising their own when it’s noticed somewhere else. I think that definitely happens. If you had success in even Australia, and definitely in England or America, it’s going to be a big deal here. People are going to notice it, they’re going to get excited. You may have already had a following, but it’s going to definitely exponentially grow from that point, there’s a glamour to that.

You can’t argue with that, it is what it is. Do Americans become more excited about their artists when they break big in England? Not really because the Americans invented rock and roll. It came from African-American people, it spread through into white culture. It became the biggest thing on the planet.

They don’t need to care about where else it’s happening. They’ve got it, they’re the crucible. In England, they’re always wanting to make it in America. It does count for a bit there, it counts hugely here. Partly because we have such a small country.

Split Enz, for example, before we went to Australia and eventually broke through there really big, we were a cult band in New Zealand. We could play the Town Hall in Auckland and in Wellington. We weren’t inconsequential. But to the level of headlining Sweetwaters in front of 60,000 people, that came with developing success elsewhere.

I just think it’s a natural thing for a small country. I don’t think it’s apathy. I might have called it that in that other interview, but I wouldn’t call it apathy now. It’s a lack of self-belief.

Do you think we still have that?

I don’t think so. There’s a lot of people now who have taken things to the world, whether it’s the various inventions or apps. Certainly, our PM gets a lot of attention internationally.

I think we feel good with where we are, but having said that, we’re in the process of decolonising and so there are historic shifts going on. We don’t know where they’re going, so there’s a bit of uncertainty, as there always is in a nation’s history, but I think it’s far less now.

With the lockdown and anxiety and a lot of stress going on out there, do you feel like there is a fundamental shift that we are going through?

I personally would doubt that it’s any different than it’s ever been, apart from the fact that because of the internet, there’s a lot of chatter. It tends to grow from there. But I think people are pretty much the same as they’ve always been.

Of course, a lockdown, a pandemic is a unique situation and we’re dealing with it as we’ve chosen to deal with it. Other countries are a bit looser about it. They’re living with it. They have been living with it for months and months. We’re still now in this ‘let’s keep it out’ phase. So it’s a different mindset to other countries, but I don’t think things have changed.

I think the noise and the chatter feeds into people’s underlying anxiety, but once upon a time it might have just been called nervous human living or normal human living. Human living is never meant to be easy. The Buddha himself said there is suffering, there is going to be suffering in everybody’s life. This place is not perfect. You can’t make it perfect. And so that’s just the same as ever.

When you look at the world that we have now with the business around music, and the noise out there through social media and everyone being able to share their opinion, does that change the role of musicians and poets?

I don’t think it changes their creative lives all that much. The record I made with Eddie for the Forenzics album, I wouldn’t have been able to make if we didn’t use the internet to exchange files and send music back and forth to each other. That would’ve been impossible back in the day.

I don’t do social media. I was told I should have a Facebook page and a Twitter account many years back when it first started up. I’ve been there about twice in 15 years. I really don’t do it. I’ll ask my management to put a little message up occasionally. It has absolutely no impact on my life at all and that’s worked really well for me. I don’t have a phone. I do email, I will always return an email [Laughs]. I like it because it’s writing and I enjoy it. I enjoy the laying out of words on a page, but the rest of it, I don’t bother with.

But I think as to your question about, do I think the role has changed for artists? The ways they can work have changed, but the fundamental role is to be inspired, is to clear the way and open yourself up to inspiration – that hasn’t changed at all.

This process of putting together a lot of these tracks over internet, what did that do to the creative process? Did it open things up or did it put limitations on things?

It was completely liberating. I would suggest, say, an idea for a section of a Split Enz song, or I might mock up a very quick loop of a section and then I’d send it to him. And he would do a really nice job on it and make it sound beautiful and send it back to me. I would sing something over it and neither of us knew what the other one was going to do. There’s always that sense of wonder and that sense of excitement when you get the email that had the track in it. It would always come back sounding a hundred times better. It was delightful.

Eddie would send me instrumentals that he had been jamming with his band and I would write songs over those. I haven’t done that process before, I haven’t written over pre-existing chords and rhythms, so it was a new feeling for me. I know it’s quite common these days as a way of working, it’s probably the main way of working now internationally.

I saw that documentary series about Laurel Canyon in the seventies, it’s really good. There was an interview attached to that which said that even in LA, people who are only one block apart don’t bother getting together to make music, they just send files. He was lamenting it as you lose because he was saying in the seventies, when those people like Joni Mitchell and Neil Young were in a room together, sparks would fly and there was a level of creative competition going on and it lifted everybody’s game and I know what he means.

But just speaking personally, I’ve done decades of that and this is a new way for me and it’s a lot of fun and it’s quite egoless in a way.

As I started listening to ‘Walking’, it just felt like it was this crescendo, this buildup. It was a very emotional thing for me and I can’t imagine how it was for you guys. What did it feel like?

The first track we did was Walking and we’d been looking at a section of Walking Down A Road, which is an early track of Split Enz. The idea had been in the ether for a while, in my mind anyway, of trying something with it based on a comment Brian Eno made 47 years ago when we were recording in London. He commented on that section and it just got stuck in my head.

So I said to Eddie, why don’t we do this? And he came back with just the most beautiful music bed where he’d looped that section and it had bass, it had beautiful keyboards, and a lot of emotion straight away. I had a tune in mind that seemed to work really well and then I thought, why don’t I just take the original words but reshuffle them, move them around, cut and paste? And I did, and it came up fairly abstract, but it’s got a deep yearning in it and a sort of pathos about it that’s hard to explain. But partly because we know that time, we know those people and we were sort of reconnecting. But also something new was coming through, something we’d never done before.

From then on, we had a huge momentum straight away to do more, it opened the door for us. We thought we had to put it as our opening track so just to invite everybody else into that as well.

What did it mean for you to sing, “Time stands still forever” 47 years later?

Phil and I wrote that song in 1973. That’s a long time ago, that’s nearly 50 years ago. We were on a hitchhiking trip, we’d written our first few songs together. We were in love with the whole process. We were in love with the world. It was an amazing time. We were just like, this is destiny writing to us, let’s answer her. We were out there hitchhiking not getting picked up on these country roads and the start of the song was that.

You’re 19, you’re 20, you’ve got somebody who you don’t wanna be with anyone else, you wanna be with that person. You wanna create a future, create a band, and dream big dreams. It’s just the best feeling in the world, complete freedom. So when I started reassembling those words, it’s not like I can go back there. You can’t. But I was having a relationship with that. Phil was kind of there and of course, we played the song to him and he liked it and was glad that it was going to be done.

We wouldn’t have done it otherwise because each of the people that we used sections of, we made sure that they were happy with it too. It was a reconnection with Phil who I haven’t seen for years and years. It just had a ready-made emotional heft to it for me.

There’s obviously a strong temporal connection between ‘Walking’ and ‘Walking Down The Road’. But then with ‘Chances Are’ and ‘Spellbound’, it seems like it’s almost a parallel universe where it felt like an opportunity to take something and try something different with it.

Definitely. Most of them were like that. We’d start with an idea of an old track, maybe do a loop and then come up with a completely different song. There’s a couple of lines of lyrics in there that are referencing Spellbound. We keyed off those moments so that the emotions of that original song stayed alive in this new song.

It is kind of fascinating. I don’t know who else has tried this, but to write a brand new song over an old motif is really interesting for a songwriter. I’ve never done it before and neither has Eddie. And then to get Phil Manzanera involved, playing the guitar solo, which is just divine and he was responding to it as well. He had produced us in London all those years ago.

To get Noel Crombie in there, such an important part of Split Enz. Noel and the whole look of the Enz, the clothes, the hair, everything he did for us. We were sort of a sculpture of which had 12 legs to Noel, he was making something beautiful out of it.

It was an interesting time, meeting different artists from different disciplines. Most of the tracks were like that they were just taken to get our starting point and then write something completely new with lyrics and tune.

How much faith did you have to have to just go with Noel’s vision?

[Laughs] We did a TV show in 1974 called the Max Cryer Show and we went on in full black and white costumes, which were an amazing set that Noel produced. Full costume and full makeup and hair and everything. It’s a very mainstream show and I didn’t warn my parents. So it comes on TV and everybody watched it, including my parents and all their friends, and there wasn’t really very much said, but I could tell they were deeply shocked in a way. Dad went to the Rotary Club and he was fined for having a son like me. Now that was a humorous gesture from the Rotarians, but it shows in the small town there must have been a lot of gossip, a lot of chatter.

Anyway, our parents were magnificent because they never really critiqued it or said anything much. It was a shock to them because that was such an extreme look, such an extreme statement that we were making. Seeing it through their eyes, I can see what a huge shift it was of their awareness of me, of who I was. In a way, they lost who they thought I was and I’ve become someone else.

It was a great time. I didn’t want to make it hard for them, but at the same time, we were just unstoppable. We were on an unstoppable journey at that point and there were no limits to it.

How do you arm your children with the capability and the confidence and the freedom to be able to go off and pursue what they want to do?

When I think back, there was one discussion that I had with my father when Split Enz had already started, where he expressed his concerns about where I was heading. I’d been at university, I’d dropped out, formed this band, which he wouldn’t have liked our music very much. Dad was huge into swing, big band and that to me was just ancient music, I didn’t go there.

The interesting thing nowadays is that kids listen to the same music. They often do listen to the same music that you or, further back, I would’ve heard. That was unthinkable for us. I would never have sat down and listened to Glen Miller or Louis Armstrong.

I think music can be a great connection point between parents and children. Our son is now doing music. Our daughter is saying she’s not sure what she wants to do, which is great. We’re glad for that in a way.

The children of musicians do tend to quite often follow their parents in, because when they’re growing up, it looks like such fun. They don’t understand the angst or the years of indifference and even outright hostility.

I’ll tell them stories about how we were literally booed off the stage at the great Ngaruawahia Music Festival in 1973. In fact, I was tapped me on the shoulder mid-song and told, ‘You have to get off’. You couldn’t imagine anything much more difficult to deal with for a performer. We were put on at the wrong time, eight o’clock on a Saturday night, everybody was drunk, they just wanted to party. We were a psychedelic folk band at that point, didn’t even have drums, so I get it.

But I would say that’s what kids don’t get, they just see it as a huge amount of fun. I want to be creative. I wanna be an artist. There’s certainly, as I say, programmes in schools, lots of chances for them to be spotted young and told that they can do anything.

I think it’s quite good for kids to not be told that they can do anything. It’s certainly encouraged, but I wouldn’t over encourage them because it’s really, really hard. They somehow have to be made to understand that, without putting them off because maybe they will end up being artists or creative people of some kind. But there’s only so many who are going to squeeze through the eye of the needle and they could reach the age of 30 and have not really gone anywhere or not be able to turn it into something that can sustain their lives.

But at the same time, these days, people aren’t as worried anymore about switching course in their thirties or even their forties. It’s much more fluid. That’s healthy. They don’t grow up thinking I’ve got to work for the man and that’s all I’ll be doing for the next 50 years. It is a time where you can make changes and pivot and I think that’s really good for people.

Generally support, encourage and notice. With music, I know that with our son, getting him to play the piano was quite hard, but I’m so glad I did it because he’s a real musician. He can play an instrument and he’s learned to play other instruments as well, but the piano gave him the freedom to write songs.

You learn chords and that opens up your world completely. The actual teaching of piano left hand, right hand, reading the notes, that may not click with the child, but chords can be done as a big pie chart. That’s what the guy taught me did, he did this big pie chart of all the chords and I could figure them out and I was free. I was liberated. It was amazing.

Do you ever have any sliding doors moments? Do you sometimes wonder what would’ve happened if you had listened to the crowd in Ngaruawahia and then just the next day left music?

It wasn’t an option to change course. We were so committed and loving it so much. Of course, we had to absorb the difficulty of that, the disappointment, the confusion of that. It probably took me a few years to really be able to look at it objectively. At the time it was a major setback, but you know, onto the next thing, let’s write a song. Nothing stopped us.

We had many of those moments in Australia as well. Cigarette butts thrown at us, beer cans. We were a very extreme band. We invited it, it was love-hate really and the lovers were far outnumbered by the haters initially. 1975 in Australia, there was still a lot of funk and still a lot of rock. Who knew that punk rock was 12 months away? Australia didn’t. Most of it was pretty funky, very influenced by African-American music and all kinds of rock and roll.

So we stood out like a sore thumb and that was fine, that’s what we wanted. We wanted our place of difference. We never felt like we were going to connect with the times. We just thought we’re always going to be outside the times and that’s how we’ll probably get noticed. It took us eight years to find any kind of a mainstream audience. I think people tend to forget that. In fact, a lot of people probably only dipped into the Enz around 1980, but we had already been going for eight years.

That seventies period is to me, the crucial part of the band’s life. That’s what made us who we are. A lot of the time we would only have each other and we’d have a rehearsal, and the rehearsals were so great. They were ecstatic at times, just making music for each other. That’s what fed us.

Where did that level of resilience and drive come from?

I think it comes out of a strong belief in what you’re doing, almost to the point where you’re not being particularly objective. If you have a very overpowering belief in what you’re doing, it may not be quite right, it might be a little bit off, but if you allow yourself to fall in love with what you’re doing, you might as well start off letting yourself completely go into it. Just be abandoned and that might give you the energy and the momentum to get you through what the struggle is going to take to get anywhere.

You hear stories these days of bands breaking up their first band meeting because they start discussing publishing splits and they realise, ‘We’re not on the same page, see you later’. We didn’t even know what a publishing deal was. So a certain naivety is also very useful. It’s very hard these days for anyone to be naive about anything. The first thing that people do if they’re going to watch a film, they Google it, they search it, they look at reviews.

The sense of unknowing has largely gone. When you’ve got a lot of preconceptions, you are already not experiencing something in a pure way. I think that’s a shame. I think it’s better to blunder into spaces and places and be surprised.

It’s one of the reasons why I don’t think you could have a Beatles now, you couldn’t have that phenomenon because to have that, you have to have a lot of unknowing. Their accents, the way they looked, everything about them was strange and exciting, and you couldn’t search them up and find out what they looked like when they were 12 or who their mates were or who their parents were.

I think that sense of mystery allowed the culture to have a moment like that, whereas now I think it’s all broken down. It’s difficult to imagine a moment like that ever happening.