The Call Of Pripyat

With shows like HBO’s Chernobyl miniseries stoking the popular imagination, our collective fascination with the 1986 nuclear disaster continues unabated. For many, it’s a distant but horrifying piece of history. For others, it’s a very real place that is very much alive and thriving, although not with the lives of the 135,000 people evacuated from the area following the explosion.

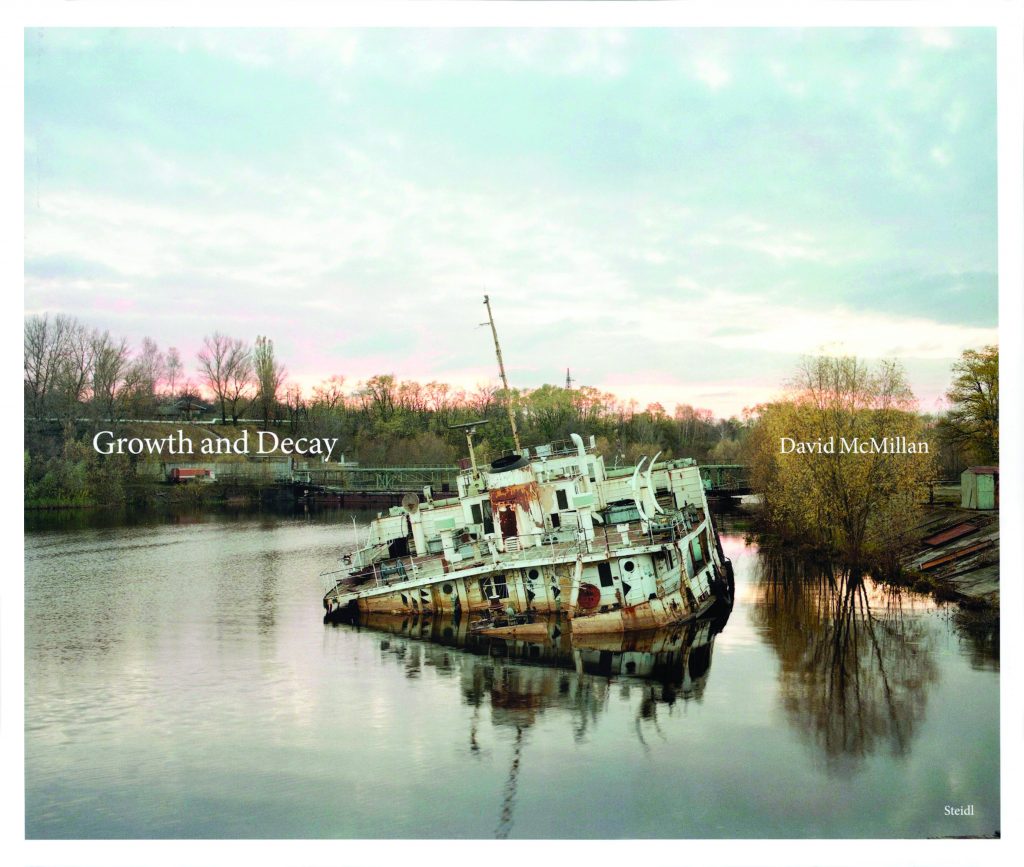

Photographer, David McMillan has been visiting Pripyat, the town immediately adjacent the powerplant, on and off since 1994, only 8 years after the explosion. In that time, he has had a unique opportunity to capture time’s effect upon abandoned civilisation. Proud flags on walls slowly fade. First their insignia disappears, then their colour, and finally their framework falls, reminding us nothing is forever.

Interview by Isaac Taylor

Header Image: Railway Station, Village of Janov, October 1996

You first visited the site just eight years after the disaster, what made you decide to go and check the place out?

For a number of years, the subject of my photographs dealt with the “tension” between the natural and the built environment and, having read Nevil Shute’s On the Beach as a teenager, I was frightened by the prospect of the aftermath of a nuclear war.

So, in 1994, when I came across a magazine article that described the condition of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone (Journey through a Doomed Land by Alan Weisman), it sounded like a place that embodied my concerns – a place where I might be able to make interesting photographs.

You mentioned once that on that first visit you weren’t sure whether you’d even be allowed in. What did it take to make it through?

Initially, getting in was a challenge. But eventually, through a series of connections, I was given the fax number of a Ukrainian filmmaker who spoke English and, because he had filmed in the Exclusion Zone, knew some of the people administering the area.

With his help, and some US currency, I gained access and was permitted to travel and photograph freely.

You were quite surprised by the changing landscape over time, what was it that initially drew you back to Pripyat?

The first visit was productive, but I felt there was still much more to see, so I returned six months later. This second visit was similarly worthwhile which led me to consider whether a third visit could yield interesting results. I decided it was worth investing the time to find out, which has been the operating principal for what has become 22 visits.

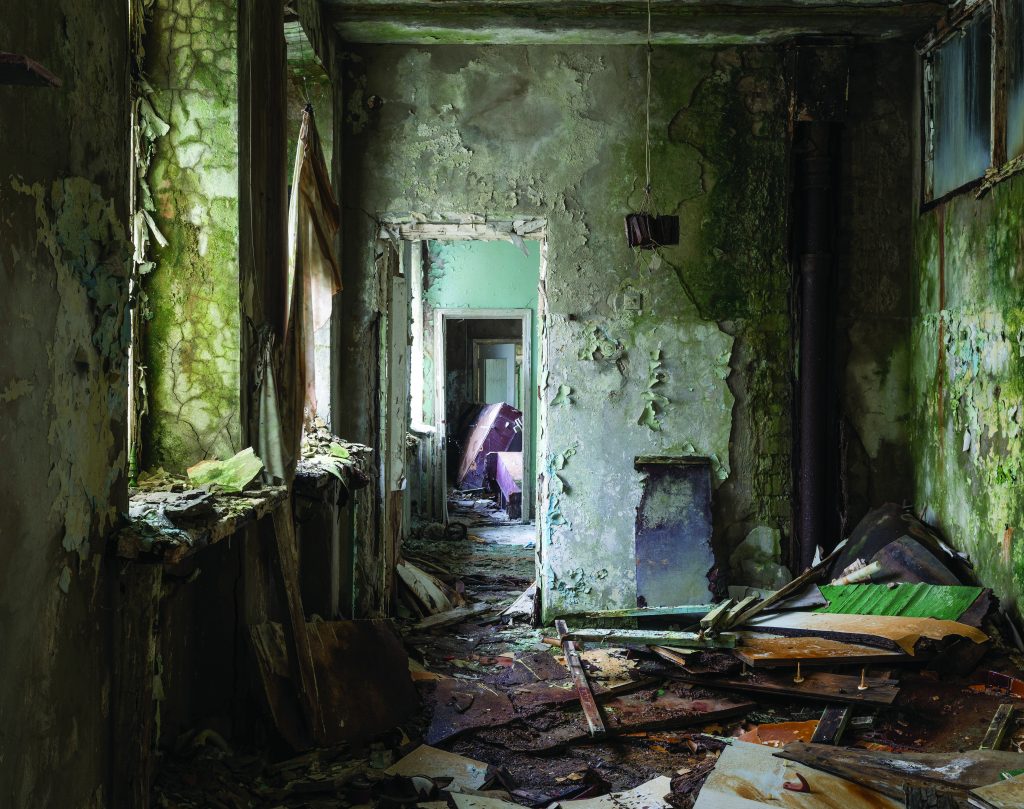

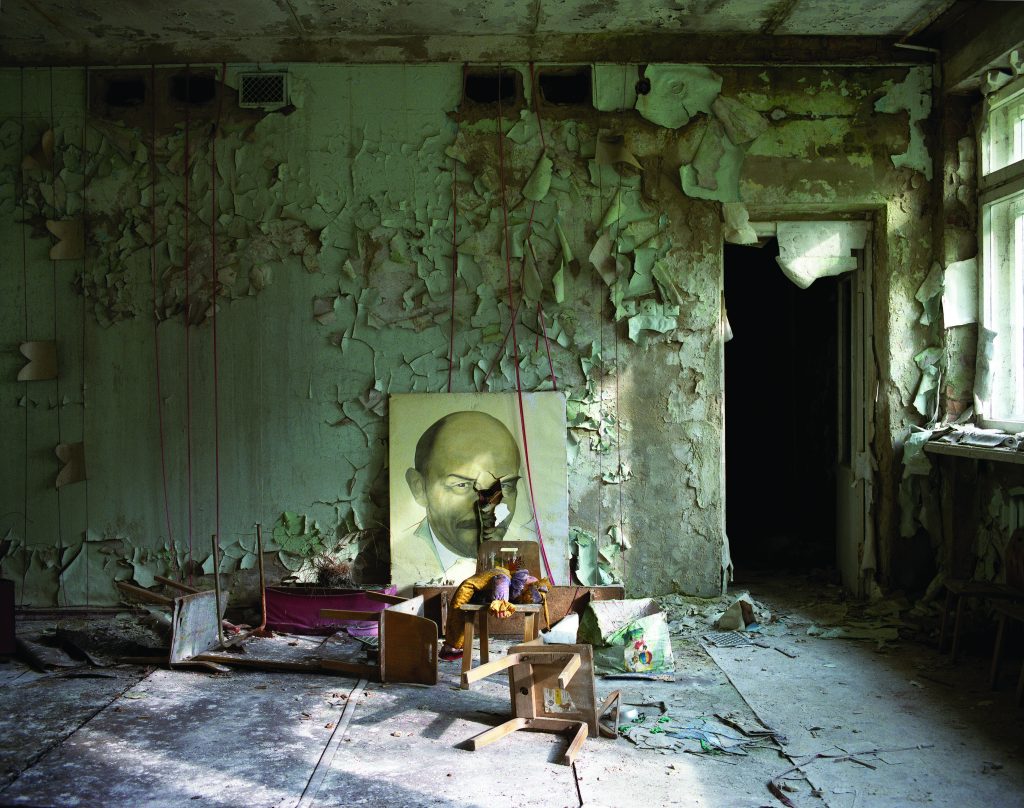

At a certain point, I realised the scope of the photographs included this remarkable growth of the natural world coinciding with the decay of the built environment.

There’s been a rise in “extreme tourism” since those early years. Have you noticed much evidence of that in your latest return visits?

For so many years, I felt as if I was the only person there. It’s been an unanticipated development to see busloads of people walking around parts of Pripyat taking selfies.

Of course, they’re as entitled to be there as I am, but I’m glad I started doing the work long before Chernobyl became a tourist destination.

Watching civilization decay like this, has it made you think differently about the places you regularly inhabit and live in?

Yes. Being in Pripyat over the last 25 years has made me keenly aware of the transience of culture. Since Pripyat and all of the Ukraine were part of the Soviet empire at the time of the accident, there are many relics of the era in the Exclusion Zone which are virtually meaningless to today’s population. It makes one mindful that nothing can be taken for granted.

The decay over time is very striking. What do you hope people get out of your images?

I’d like to think that if this succeeds as art, it generates complex emotions – including the apprehension of beauty coupled with the tragedy implicit in what is being described.

I imagine some people will look at it because of a curiosity about the aftermath of the accident. Some will have their environmental views reinforced and see it as a warning.

Do you have any other projects you’re working on, or places you’d like to visit?

As an art student, my major area of interest was painting, which is something I still do. There are many places I’d like to visit, but I’m not through with Chernobyl.

For me, it has a scope and complexity that I’ve yet to find equaled anywhere else.