The Rabbit Hole of Wellness: Scams, the Rise of Conspirituality and Corporate Subterfuge

The wellness industry has been growing like wildfire over the last few years. People seem more conscious than ever about their minds and bodies, and they have their credit cards on quick save for ways to stay healthy or “Nourish the Inner Aspect”, as is the tagline of Gwyneth Paltrow’s $250 million wellness company, GOOP. The industry has responded to this frenzy by offering up all variety of products and services, ranging from fitness apps to organic foods, wellness retreats and apparently even USB sticks that will stop both 5G and Covid.

In fact, many of the products and services that are marketed as “healthy” are actually harmful or ineffective. Moreover, the industry preys on people’s fears and insecurities, promising them quick fixes and miracle cures that simply do not exist.

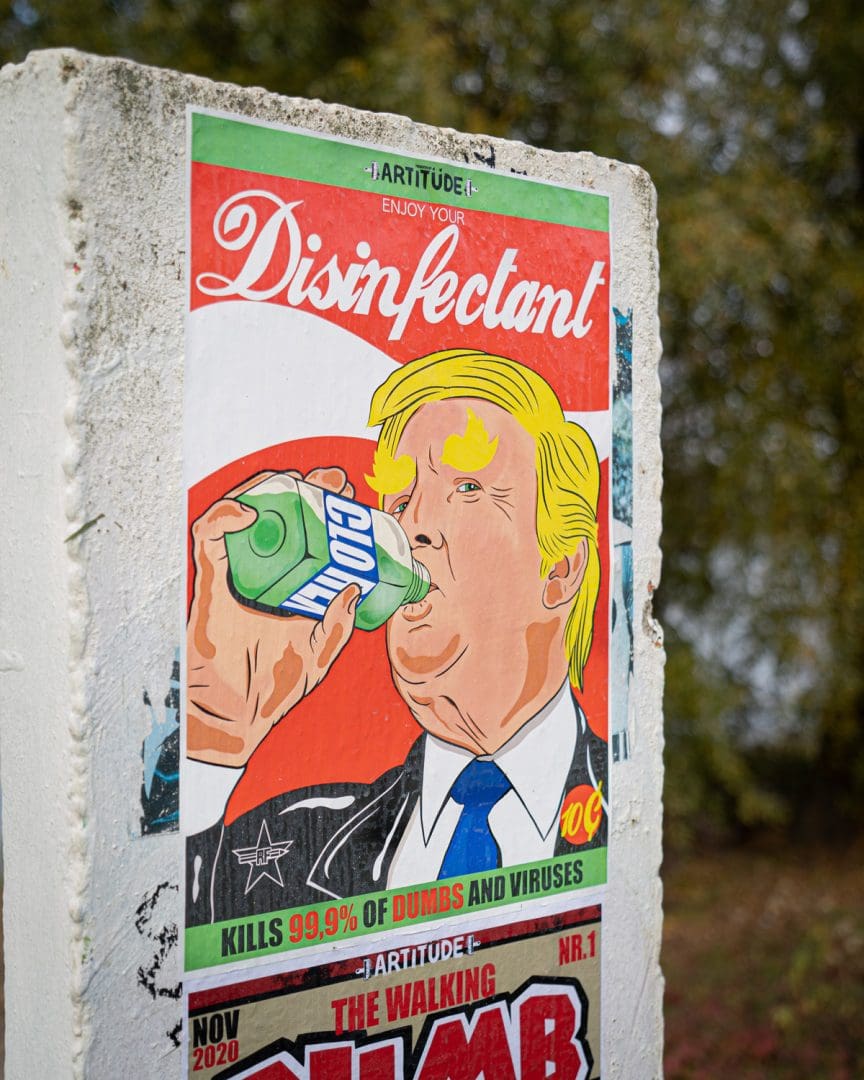

The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic saw a significant increase in scams related to health and well-being. With widespread fear and uncertainty, people were desperate for ways to protect themselves and their families from the virus. This desperation made them vulnerable to false claims and products marketed as solutions to the pandemic.

One notable example of this was the promotion of vitamin and mineral supplements as a means to boost the immune system and fight off the virus. While some vitamins and minerals play a role in immune function, their impact on COVID-19 specifically remains unclear. Nevertheless, supplement manufacturers seized the opportunity to market their products as essential for virus prevention, exploiting the public’s fear and lack of knowledge.

The pandemic also saw the proliferation of counterfeit personal protective equipment, such as masks and gloves. These products were often of poor quality and failed to provide the necessary protection against the virus, putting users at risk.

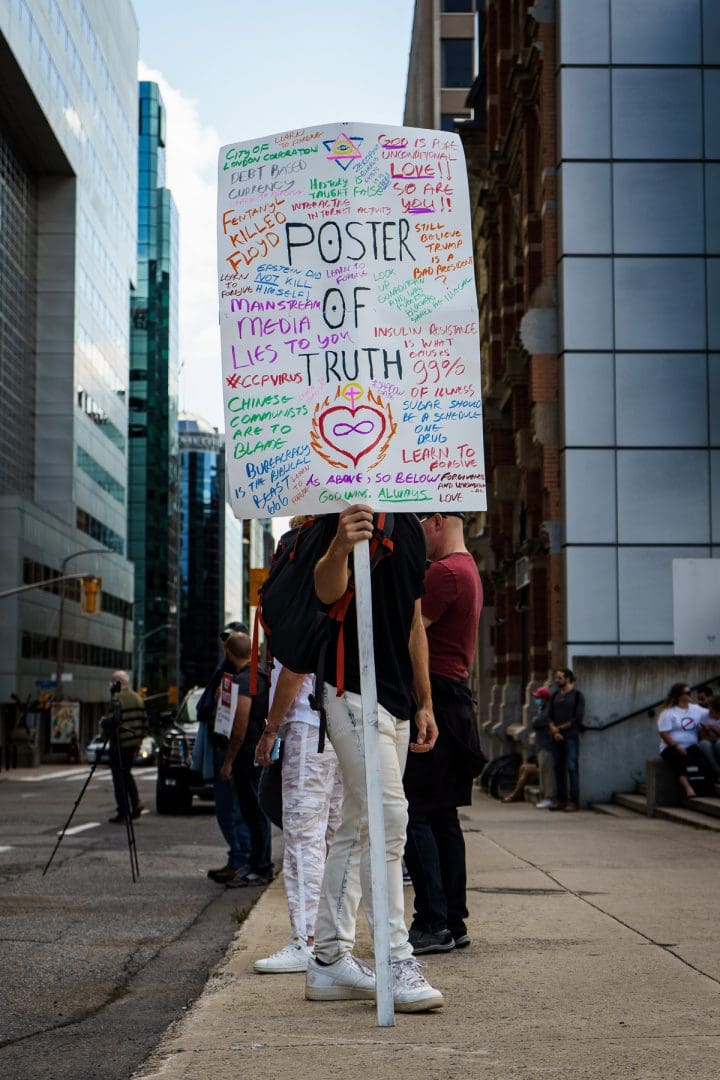

As well as scams and false promises, the pandemic seemed to fuel an intersection between some in the wellness industry and conspiracy theories. An example of this crossover was the rise of the “Plandemic” conspiracy theory. This theory claimed that the virus was intentionally released as part of a global plan to control the population, and it was fueled in part by individuals within the wellbeing industry. The theory gained traction on social media and was widely shared, leading to a significant amount of fear, confusion, and mistrust in the scientific and medical communities.

Wellness and conspiracy theories have been strange bedfellows prior to the pandemic. The term “conspirituality” was coined in 2011 by Charlotte Ward and David Voas in a paper published in the Journal of Contemporary Religion, describing the intersection of conspiracy theories and spirituality. They suggest that the wellness industry’s focus on self-empowerment and questioning the status quo has also made it an attractive breeding ground for conspiracy theories. The growth of the wellness industry, now worth $4.5 trillion, has enabled conspiracy theories to be packaged and sold as part of wellness practices.

Dr. Timothy Caulfield, a researcher who studies misinformation suggests, “The toleration of wellness pseudoscience has helped to fuel the current situation. There is a strong correlation between the embrace of ‘wellness woo’ and being susceptible to misinformation. And as conspiracy theories and misinformation become increasingly about ideology, it becomes easier to sell both wellness bunk and conspiracy theories as being ‘on brand.’”

And speaking of on brand, many individuals in the wellness industry seem to have resonated with QAnon content. Melissa Rein Lively, a former wellness and spirituality influencer, explains that she noticed many wellness influencers she followed shift their content to focus on QAnon theories during the pandemic. “Much of what I read took a hard stance against the pharmaceutical industry and Western medical philosophy, and was particularly critical of individuals like Bill Gates, who seemed to have an incredible amount of influence and involvement in public health policy,” says Rein Lively. She was initially drawn to the community and alternative thinking, but as she delved deeper, she found herself becoming convinced of conspiracy theories.

Abbie Richards, a TikTok influencer who creates videos debunking conspiracy theories, explains that the connection between wellness and QAnon is rooted in a distrust of authority. “If you don’t believe in climate change, you’re saying you don’t trust the scientists. If someone is feeling discontented, these ideologies provide them with a sense of community, and someone to blame,” she says. The wellness industry’s focus on alternative remedies and practices can lead individuals to seek out alternative theories, including conspiracy theories like QAnon, as they question mainstream authority and institutions. As conspiracy theories continue to gain traction, it is important for individuals in the wellness industry to use their influence responsibly and prioritise scientific evidence over pseudoscience.

“There’s a growing overlap between wellness and conspiracy thinking. Both involve questioning mainstream narratives and seeking alternative answers, which can make it easy for conspiracy theories to gain a foothold in the wellness community,” explains Dr. Matthew Browne, a researcher on the psychology of conspiracy theories. Browne warns that in order to maintain a healthy balance and avoid falling prey to scams or conspirituality, it’s essential to incorporate reliable sources of information into our wellness journey. Consulting reputable scientific research and seeking out experts’ advice can help us make informed decisions and avoid the traps laid by opportunistic scammers and the allure of conspirituality.

“It’s never been more important for wellness influencers to use their influence well. We need voices within the communities who understand the values and experiences of people who have embraced wellness and conspiracies,” says Dr. Timothy Caulfield, author of Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything?

And if we are talking about influencers, we must also acknowledge the role that social media plays in the dissemination of wellness misinformation and conspirituality. The algorithms used by these platforms often prioritise sensational, controversial content, which can inadvertently lead users down rabbit holes of false information and dangerous beliefs. “Social media platforms can be a breeding ground for conspirituality and misinformation, as their algorithms tend to reward controversial and emotionally-charged content,” warns Claire Wardle, the executive director of First Draft, a non-profit organisation dedicated to fighting disinformation. “It’s crucial for users to be aware of this and to critically assess the information they encounter online.”

Social media algorithms might be a big driver but there’s also individual psychology at play and unfortunately, people who are looking into wellness might also be in a particularly vulnerable state or desperate for solutions and maybe prone to spending large amounts of money on products and services that offer no real benefits. This can be particularly devastating for those who are already struggling financially due to job loss, medical expenses, or other factors. From weight loss pills to detox teas, these scams can be both financially and physically harmful.

As our society becomes more health-conscious, companies and individuals have capitalised on this trend by marketing their products and services as solutions to various health challenges.

Wellness washing is a deceptive marketing technique that taps into the public’s desire to be healthy, and it can have detrimental effects on the consumers who fall for these scams. These tactics are especially harmful when they exploit people’s vulnerabilities, such as during times of crisis or when they are desperate for solutions.

Brigid Delaney explored the pseudoscience and false claims that are prevalent in the wellness industry in a 2018 Guardian article and we all saw how much things ramped up just a couple of years later. She notes that many of the products and services that are marketed as “healthy” are not backed by any scientific evidence, and some are even harmful.

One example she cites is the “raw water” trend, in which people pay exorbitant amounts of money for untreated, unfiltered water that is supposedly more “pure” than tap water. However, as Delaney points out, raw water can contain dangerous bacteria and parasites that can cause serious illness. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that raw water is any healthier than tap water.

Delaney also notes the proliferation of wellness gurus who promote dubious practices like “colon cleansing” and “oil pulling.” These practices are often based on pseudoscientific claims and have no proven health benefits. In some cases, they can even be harmful, as in the case of colon cleansing, which can disrupt the balance of bacteria in the gut.

Delaney also argues that the wellness industry’s focus on “natural” and “organic” products is often misguided, as many natural substances can be just as harmful as synthetic ones. For example, she points out that tobacco and arsenic are both natural substances, but they are also highly toxic.

“Many wellness products are marketed with exaggerated claims, and some may even be dangerous. It’s essential to do your research and consult with a healthcare professional before trying any new product or practice,” says Dr. Nina Shapiro, author of Hype: A Doctor’s Guide to Medical Myths, Exaggerated Claims, and Bad Advice.

And aside from the exaggerated claims, scams and conspiratorial rabbit holes, there may also be another less obvious side effect of a heightened focus on wellness. Researchers from the University of Otago recently highlighted the concept of a “wellbeing pandemic,” in which the global drive for wellness might be making us sick (Jackson et al., 2023). The article argues that the misuse and exploitation of the term “wellbeing” contribute to a sense of malaise in society. Two main perspectives of wellbeing—subjective wellbeing, which focuses on an individual’s mental, physical, and spiritual health, and objective wellbeing, which offers an alternative to GDP as a measure of national prosperity—have become prominent.

And as wellbeing has become a cultural phenomenon, the authors warn of the phenomenon of “wellness washing” which occurs when organisations use language, imagery, policies, and practices related to wellbeing to project a positive image, while their underlying motives might actually be focused on productivity, cost reduction, and surveillance. The paper suggests that the wellbeing agenda is often deployed poorly or cynically, resulting in a strategic attempt to use wellbeing as a means to advance an organisation’s interests.

Dr. Carol Ryff, a leading expert in psychological wellbeing, has explained that “the field of wellbeing is rife with conceptual ambiguities and measurement challenges”. Wellness washing presents several dangers to both individuals and society as a whole. For one, it can lead to a sense of obligation and stress, as participation in wellness initiatives might be seen as a semi-obligatory work task. Non-participation could lead to stigmatisation, further exacerbating stress and, ironically, contributing to unwellness.

Dr. André Spicer, a professor of organisational behaviour at Cass Business School, has noted that “wellness programs can sometimes be a source of stress themselves”. Furthermore, poorly implemented wellness programs might not adequately address the root causes of stress and unwellness, focusing instead on superficial solutions that only serve to mask deeper issues.

One example of wellness washing can be found in the workplace, where organisations may offer wellness programs or activities without addressing systemic issues that contribute to employee stress, such as overwork, inadequate compensation, or lack of job security. By focusing on individual wellness initiatives, organisations can deflect attention from the broader structural problems that may be causing stress and unwellness among employees.

Whether it’s corporate or individually driven, the wellness industry undoubtedly has the potential to provide meaningful and lasting improvements to our lives, but it’s crucial to remain discerning as we navigate this complex landscape.

“The pursuit of wellness is a personal journey, and it’s essential to recognise that no one-size-fits-all solution exists. Each person must find their own path to wellness, but this should always be guided by evidence, reason, and a genuine desire to improve one’s health and well-being,” emphasises Dr. Andrew Weil, a prominent integrative medicine physician and author.

Remember, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to wellness, and what works for one individual may not work for another. By focusing on evidence-based practices, consulting with healthcare professionals, and engaging in critical thinking, we can create a personalised wellness journey that is both effective and safe.

“At its core, wellness should be about self-care and nurturing the body, mind, and spirit,” says Dr. Deepak Chopra, a prominent figure in the field of integrative medicine. “When we approach wellness with discernment, curiosity, and a commitment to evidence-based practices, we can create a lifestyle that truly supports our well-being and fosters a sense of harmony and balance.”