The View From Above

Everyone bar none knows about NASA. The American space juggernaut has been around since the late 1950s and was responsible for the first manned mission to the moon. That said, the organisation has an almost mythical feel to it from here in New Zealand. We see the news about the missions, astronauts and even watch the live feeds of the astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS), but the extent of the work they are doing can feel almost unfathomable. So instead of lying on our back deck staring up at the stars, wondering what if?, we took the 12,000-kilometre journey to the Johnson Space Centre in Houston to explore the facility and discover more of the groundbreaking feats they are taking on.

uring the one-hour drive from Houston to Johnson, I couldn’t help but imagine what to expect; I pictured a desolate area something like ‘Area 51’, with a three-metre fence slicing through the earth, and a guarded entry for security, but as we passed through the domesticated area of Johnson, the NASA signs directed us straight through the centre of the suburbs. Before we knew it, we were there, standing in front of the infamous NASA, the place where dreams are made and the home of some of the most brilliant and qualified people on Earth, (that is, when they aren’t in space orbiting Earth).

ABOVE: A group of US Navy divers, Air Force pararescuemen and Coast Guard rescue swimmers practice ‘Orion underway recovery techniques’ in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at NASA’s Johnson Space Centre to prepare for the first test flight of an uncrewed Orion spacecraft with the agency’s Space Launch System rocket during Exploration Mission (EM-1).

Johnson has been the home of Mission Control since 1963, and subsequently put Neil Armstrong on the moon in 1969. But aside from 24/7 flying and controlling the ISS and the planning research taking place on the ISS, this enormous facility is also where a significant amount of astronaut training and preparation is conducted. Every two to five years, some 18,300 eager applicants undergo a scrupulous process in the hopes of becoming one of the few selected to partake in a two-year basic astronaut training at the Houston facility. From this selection of candidates, even fewer are chosen to undergo full astronaut training. This training covers outdoor survival training, simulated malfunctions on a mock-up of the ISS, Russian lessons, spacewalk training in the NASA pool and then there is the mental training to make sure you are up to the mental strain and situations you could be facing. After two years of this intensive training, you hope you’ll be facing a panel of astronauts and psychologists for a NASA job interview. “In the first interview, they try to get to know you. In the second they clinically dissect aspects of your past,” astronaut Victor Glover shares with Red Bulletin in an interview. “It’s a challenge for everybody who comes into the astronaut training programme. But you’re learning from the best.” Glover is one of eight members from the astronaut class of 2013, for which there were more than 6000 applicants. He is yet to travel into space but is fully prepared for the possibility. Glover faces the possibility of being selected to be part of the crew of Orion, (NASA’s latest spacecraft, it’s first manned flight is scheduled for 2019).

As we are taken through a broken down, life-sized replica of the ISS, the reality that this is where people work on a daily basis begins to sink in. We see a NASA robotics engineer working on a robot that will be sent into space in years to come to help with missions and I just can’t even begin to imagine what he knows and what is going through his brain to be able to bring this piece of metal to life, so that it can conduct tests and move and walk with life-like demeanour.

Aside from brushing shoulders with real life astronauts, robotic engineers and commanders as we tour the facility, the moment that resonated with me – about the scope and extraordinary feats that NASA has and continues to achieve – was sitting in complete silence, in a glass-enclosed room behind 20 or more people all intently monitoring screens of data and imagery; they are the team from Mission Control! There is something about the mood in that room that was completely indescribable. Everyone moved with purpose, acted with intent and kept completely composed, collectively they are all responsible for the continued flight of the US$150 billion ISS and conducting unimaginable activities to keep the missions on board running smoothly.

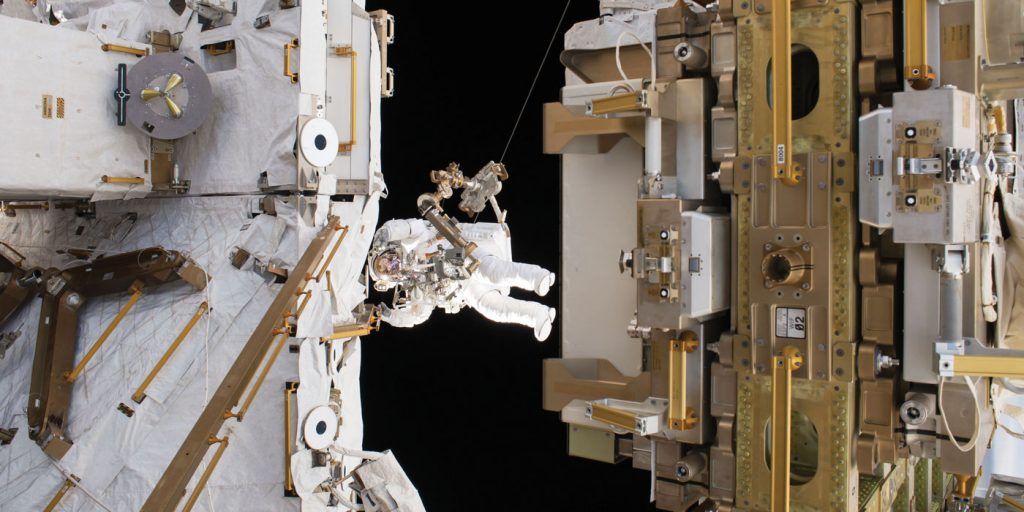

Missions are planned months in advance, and all possible outcomes are rehearsed to prevent possible disaster. A routine spacewalk is planned nine weeks ahead, but sometimes things on board the ISS don’t go to plan, and as astronaut Tom Marshburn describes, they have to be ready for those situations. On May 11, 2013 Marshburn had to prepare for an emergency spacewalk where there had been an ammonia leak, and he and Chris Cassidy had only 36 hours to prepare as opposed to the usual nine weeks. “I opened my laptop on the ISS and launched the virtual reality program. That way I could see every square centimetre of the space station from the outside and commit it to memory… But we train for that in Houston, too. You put on the VR headset and the programmers beam you to a like-for-like model of the ISS and have you spinning for about 30 seconds until you are disorientated. You then have 30 seconds to fly back to the station with this little jetpack controller. The toughest thing is you only have one attempt. Your first burst back in the right direction has to be very good,” he shares in the same interview with Red Bulletin.

RIGHT: A deconstructed replica of the ISS at the Johnson Space Centre, used for the astronauts to train in.

From Mission Control, the team has complete control of the ISS. They regularly fly it back into the right position, as over the course of 24 hours, it drops in altitude. They control the robotic arm, which is regularly used to assist the astronauts on various missions, such as grappling commercial cargo crafts when they arrive at the station.

Exploring the halls, laboratories, training facilities and more at the Johnson Space Centre was a true experience. I left with a new level of respect for those incredible people behind NASA and, from the few hours spent inside, it made me realise that anything is possible. It changed my mindset; I now realise it’s not about looking at something and thinking about the reasons why you shouldn’t or can’t achieve it, it’s about looking beyond that and thinking about how you can make it happen. NASA has put a man on the moon, built a research facility that operates constantly in Earth’s orbit and has plans for a manned mission to Mars.

So, next time you find yourself lying on your back deck staring at the stars, wondering ‘what if?’, I hope you are inspired to chase your dreams and shoot for the moon.

ABOVE: Expedition 35 Flight Engineers Chris Cassidy (pictured) and Tom Marshburn (out of frame) completed a spacewalk at 2:14 p.m. EDT May 11, 2013 to inspect and replace a pump controller box on the International Space Station’s far port truss (P6) leaking ammonia coolant. The two NASA astronauts began the 5-hour, 30-minute spacewalk at 8:44 a.m.

A leak of ammonia coolant from the area near or at the location of a Pump and Flow Control Subassembly was detected on Thursday, May 9, prompting engineers and flight controllers to begin plans to support the spacewalk. The device contains the mechanical systems that drive the cooling functions for the port truss.

Lunar, Martian Greenhouses Designed to Mimic Those on Earth

While astronauts have successfully grown plants and vegetables aboard the International Space Station, NASA scientists at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida are collaborating with a university team to develop long-term methods that could help sustain pioneers working in deep space.

Agency researchers believe while there are many challenges for human exploration beyond Earth, they are convinced there are solutions. According to Dr. Ray Wheeler, lead scientist in Kennedy Advanced Life Support Research, the Prototype Lunar/Mars Greenhouse project will support ongoing research in space to grow vegetables for food and cultivating plants to sustain life support systems.

“We’re working with a team of scientists, engineers and small businesses at the University of Arizona to develop a closed-loop system,” he said. “The approach uses plants to scrub carbon dioxide, while providing food and oxygen.”

The prototype involves an inflatable, deployable greenhouse to support plant and crop production for nutrition, air revitalization, water recycling and waste recycling. The process is called a bioregenerative life support system.

Back on Earth at the University of Arizona in Tucson, tests involving the Prototype Lunar Greenhouse have included determining what plants, seeds or other materials should be taken along to make the system work on the moon or Mars.

Learning what to take and what to gather on site will be crucial for living on distant locations. Using available resources located or grown on site is a practice is called in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU.