Zirk van den Berg On How To Write Hits

Zirk van den Berg is one of those writers that has the power of the village and the writer all in one. He has a lot of accolades and awards under his belt, alright. Moving from Mowbray, South Africa to Auckland in 1998, with already two acclaimed published books under his belt, Zirk van den Berg released Nobody Dies in 2004. That year, the NZ Herald rated it one of the five best thrillers of the year and the NZ Listener speculated that he may be the best thriller writer in the country. So it’s no surprises that that book went on to win the KykNet/Rapport Award for best filmable book in South Africa in 2014 and the movie came out last year to wide acclaim.

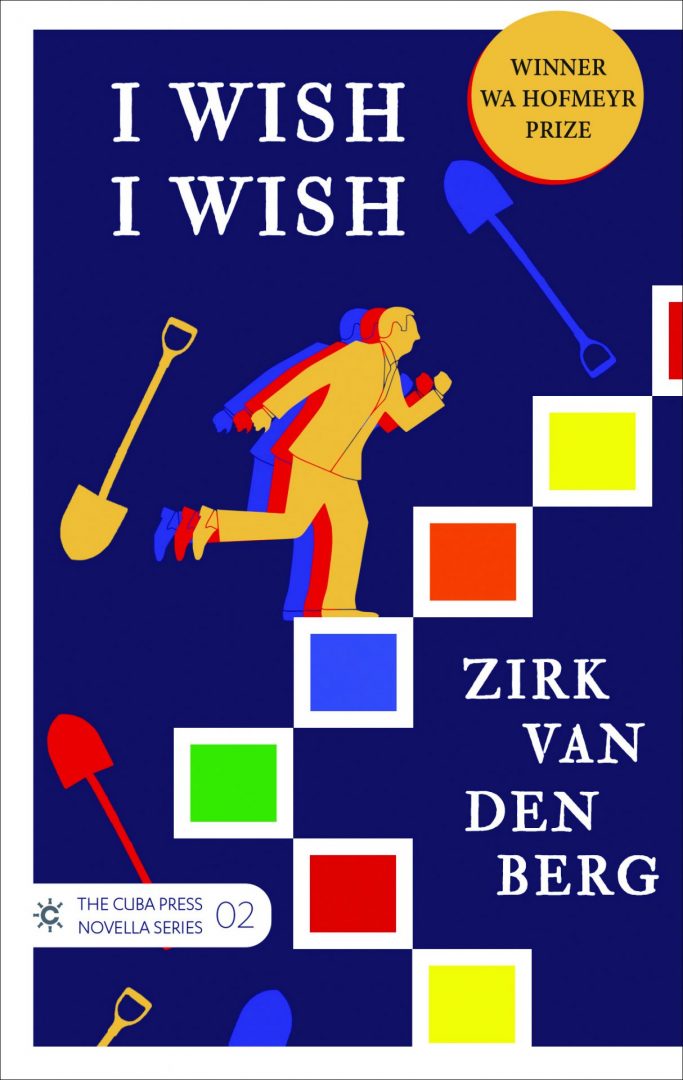

Zirk van den Berg went on to write five bestselling books in Afrikaans and English, making him one of the most hardworking writers in the country. In October this year, Zirk’s latest literary offering, I Wish, I Wish, was published by The Cuba Press. There’s something uniquely different about this novella, something darkly comic and refreshing. It’s no surprise that it’s been awarded the prestigious WA Hofmeyr Prize for van den Berg’s outstanding writing.

We got to sit down with Zirk van den Berg on the lead-up to the release of I Wish, I Wish.

What made you start writing?

Saul Bellow said a writer is a reader moved to emulation, and that seems true to me. I write because I like to read. Sometimes there is a particular book I want to read and I can’t find it, so I write it myself.

I wrote my first stories at 12 years old and never stopped. I’ve just not always been lucky or good enough to get my stuff published, so there were long gaps in between. My first magazine story appeared just before I turned 19. I published two books in my native Afrikaans around the age of 30, then migrated to New Zealand and had a break of a decade before Random House NZ published my crime story Nobody Dies. Then another ten years before its Afrikaans translation heralded a career renewal in South Africa.

I have published five books over there in the last seven years, two of them in both Afrikaans and English. I also published translations of three Wilbur Smith novels, two by Philip Kerr and cricketer A.B. de Villiers’s autobiography. The Nobody Dies translation, by the way, won an award as best filmable book. Though the book is neither action packed, nor a comedy, it was made into a Tarantino-esque Afrikaans action-comedy that had a cinema release last year.

Where do you get your biggest inspirations from?

Where do you get your biggest inspirations from?

I am inspired by artists who follow their own vision, damn the consequences – by authors, as well as musicians. It doesn’t have to be high art. The sci-fi writer, Philip K. Dick and a crime writer, such as Jim Thompson both have the kind of vision that inspires me. Also, Kurt Vonnegut and the French writer, Romain Gary.

What is the most difficult part of your artistic process?

The most difficult is also the most rewarding. Rather than write the kind of stories that I know people will like or that I know I can write, I am most enthused when I’m working on something that challenges me and I’m not sure if it will work or not.

Tell me about your new novella, I Wish, I Wish.

I Wish, I Wish is the story of a mortician who comes to believe that he can make one wish that will come true. This, coupled with some personal disasters, causes him to re-evaluate his life and find an answer to a question we can all ask ourselves: If I could wish for one thing only, what would that be? It is a simple story, uplifting, and short enough to read in an evening.

Was the character Seb inspired by a real person?

No, although I guess as a writer you tend to draw on aspects of yourself for your characters. Not because you are anything special, but simply because you are the person you know best.

Seb is a rather drab fellow, but not beyond harbouring dreams.

Did you edit any big changes out of the final manuscript?

Writing, I believe, is about creating text you can edit later. Rewriting is vital. But this is the one book of mine that I wrote in few weeks flat, with relatively few changes afterwards

I had written the key scene of the boy coming to try on a coffin way back in 2011, but never knew what to do with it. Was it a movie, TV series or novel?

Then, in 2017, I was a bit frustrated when I struggled to find a publisher for books that had since been published. At the time, I decided to take the best idea in my drawer and work on that instead. That was I Wish, I Wish. I wrote it in English and translated it into Afrikaans, which was then published.

Later, while trying to rework it as a film script, I realised that a particular type of tissue box explained an element of the story, and that box has now been included in the new English version.

So, to answer your question: I added a tissue box! The editing for this edition was mostly about words and sentences, not the story itself.

How did it feel winning the WA Hofmeyr Prize for I Wish, I Wish?

After I had won that award, a South African journalist quoted an earlier interview where I said that this is not the kind of book that will ever win an award. That is what I genuinely thought. It’s such a small, simple book.

On the award night, which was at some ungodly hour of the morning in New Zealand, I didn’t even wake up for it – I was convinced that the 600-page magnum opus, by probably the most celebrated novelist in Afrikaans, would win.

A phone message woke me up and I was in a total daze. I laughed like an idiot. It was wonderful. Then, in September, the book won two more awards – the kykNET-Rapport Prize for fiction as well as the award for best filmable book.

The fact that three separate judging panels decided to give this book an award against strong competition amazes me still. The Afrikaans language community is about one and half times the size of New Zealand, and it has a vibrant literature. More than 50 novels, all from 2019, were entered in the latter awards, so winning was no small miracle.

What surprised you the most when writing the book?

How easy it was. I’m used to slaving over books for years. This time, I knew the story from the outset and simply told it from start to finish, without bothering with subplots or how long it was.

The length – less than half as long as most novels – was a stumbling block to some New Zealand publishers. Apparently, people are happy to watch a two-hour movie, but not to read a book that can be finished in that time, don’t ask me why. I love The Great Gatsby, and that’s a short book too. Fortunately, Cuba Press decided to take a chance on it.

How would you define ‘writing success’?

For me, it’s finding an audience. It is a wonderful feeling that there are people who read and enjoy something that was meaningful to me to create.

Over and above that, critical recognition is good for the ego – there’s no denying that. And I have to say it would be great if I could make a living from my fiction. However, for that to happen, I would have to become incredibly lucky and probably stick to a particular type of book in a popular genre, to establish a brand. And I don’t think I can ever write just one kind of story.

So far, I’ve written short stories, crime, historical fiction, this modern-day fable, and have just received the news that a story with a strong sci-fi element was accepted for publication. In my more deluded moments, I tell myself that this restlessness is the only reason I’m not rich and famous!

Have you got your next project in mind?

I wrote I Wish, I Wish back in 2017, and have completed three more books since then – one came out a few months ago, one is slated for publication in 2021 and another in 2022. So, in terms of publishing, the pipeline is full.

I was working on a historical novel at the beginning of the year, but the research required overseas travel, so COVID put that on hold. Now I’ve started tinkering with something else, which may or may not work. Isn’t that fun?