Brain Power: Adding the Soul to Machines

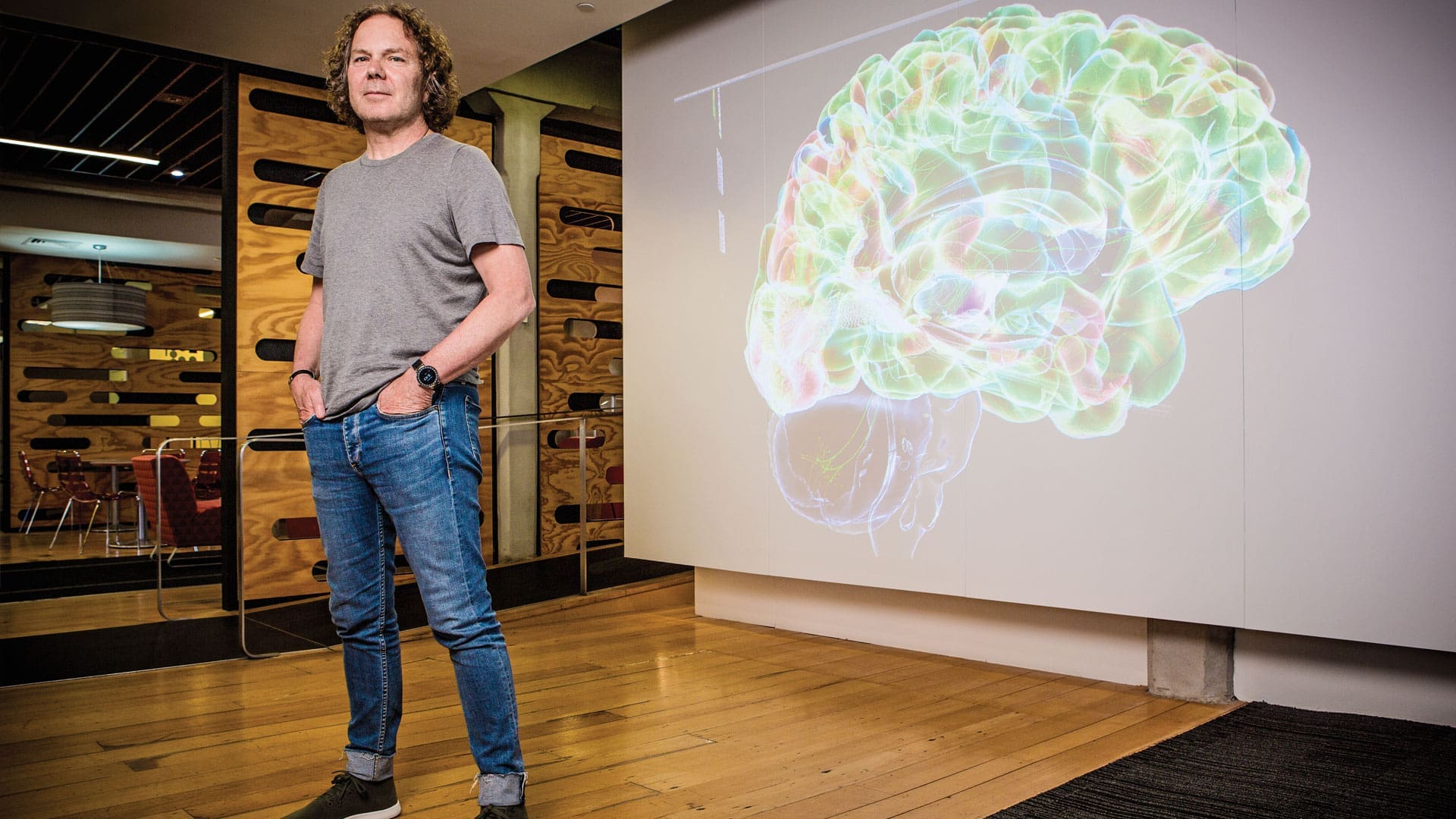

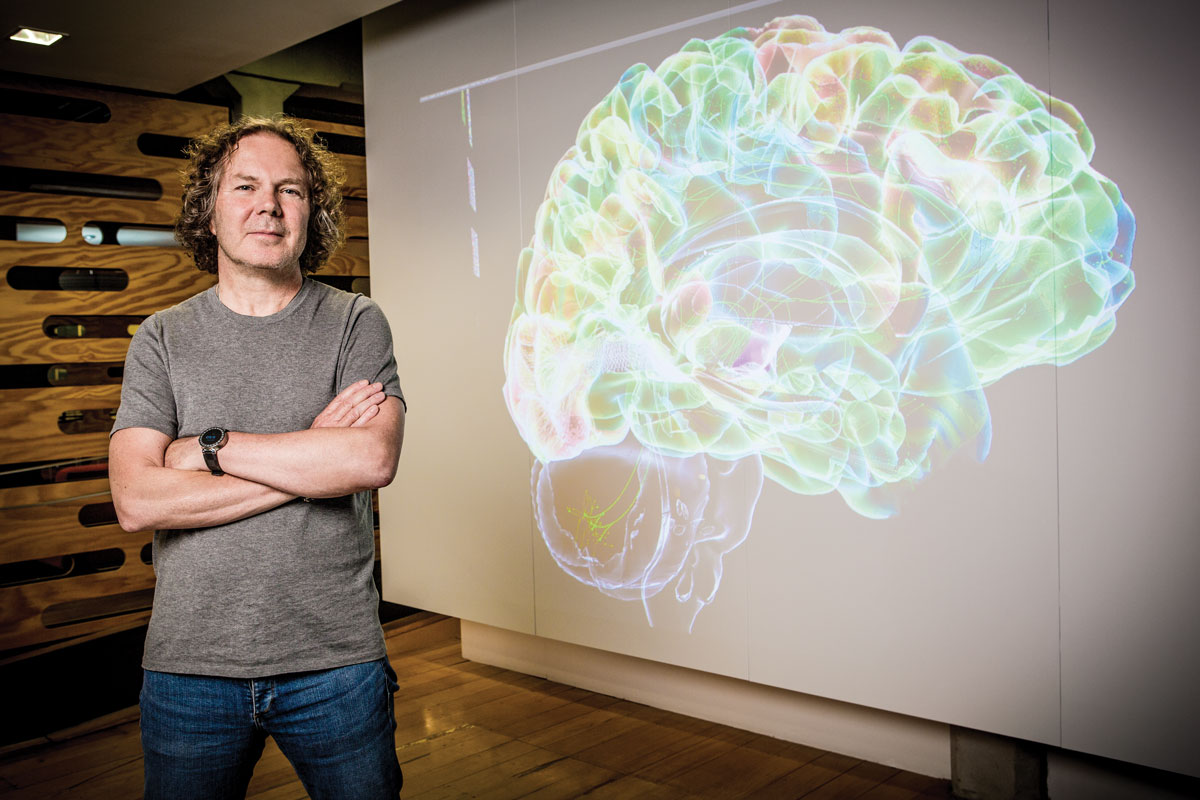

To say that Greg Cross seems to have a knack for creating business opportunities out of new ideas and technology is a vast understatement. Think more the creation of industries and you are more on the money. Greg played a lead role in PowerbyProxi, one of the world’s leading wireless power companies based on technology out of University of Auckland, which was sold to Apple for a multimillion dollar sum in 2017. And if that wasn’t enough excitement for one entrepreneur, while this was happening he was also building another ground-breaking company out of University of Auckland technology with Dr. Mark Sagar and his BabyX technology. The result is Soul Machines™, a company that uses “neural networks that combine biologically inspired models of the human brain and key sensory networks to create a virtual nervous system™” to not only create smarter and faster learning AI, but to also add an emotional connection to our interaction with computers. Their creations have already been rolled out for customer experience duties for some of the world’s top companies and it’s changing the face of that customer experience. But this is only the very beginning.

In terms of the overall concept of what you’re doing, it seems like a really exciting, really cutting edge place to be. What is it that you enjoy about the role that you have in particular?

I guess there’s two concepts to it. One is the incredible opportunity to make a difference. I mean a really, really big difference, to the lives of millions of people. We absolutely believe this is not about just replacing people’s jobs or about delivering better services to everybody; it’s about the democratisation of personalised service and specialised knowledge. That’s something that’s enjoyed only by a handful of people today. You can almost go across any industry in the world; healthcare, education and there’s this phenomenal opportunity to have better quality interactions and better quality education, better quality healthcare with this type of technology. So that’s one aspect to it, the impact that we believe it will have over the next five to 10 years.

And the second aspect of it is the enormous creativity that’s involved in it. I go from talking to and working with some of the biggest CEO’s from some of the biggest organisations in the world, to working with some of the biggest celebrities and managers in the world. So I’m in an incredibly creative business as well, thinking about crazy stuff and then figuring out how to make it happen. How do you bring somebody who’s been dead for a long, long time back to life? How do we immortalise people who are our icons from the 20th century, who might be near to the end of their natural life, or their analogue life? These are things that are possible now, so these are incredible things to think about, and then figure out how to do it. That’s what’s really cool about what we’re doing.

Are there certain things within that that you really gravitate towards as part of your role?

The technology we’re building. We’re at the very early stages of the way in which we use it, the way in which we can imagine using it, the way in which AI is actually, really having an impact in the world. There’s lots of talk, there’s lots of hype. So the thing that’s most interesting for me is getting to work with some incredibly visionary CEO’s and leaders, people who want to be first. People who are actually being quite courageous in some of the discussions they’re being prepared to have about the future and the way they’ve been prepared to think about the future of their industry.

To me, what the really fun part is the incredible people who are really wanting to learn and experiment about the future and the future of that customer experience, the future of the way in which brands will engage with fans in the future.

Do you see an evolution and a future in which Soul Machines would be involved in many other industries?

Oh yeah, absolutely. There’s a number of ways to think about our technology, but the really, really key part is the science that we have that enables digital characters to be autonomously animated. If you think about digital characters, you’ve got Hollywood and the games industry and they spend months and months and months, in some cases years, building their digital characters. And then it costs a huge amount of money to animate them. They’re achieving lifelike, emotionally connecting animation. If you look at movies like Avatar, my business partner and the inventor of our technology, Dr Mark Sagar, came up with and he won an Academy Awards for his work on that.

But if you look at the state-of-the-art of digital character animation, it requires an actor, or it requires motion capture, so animation is pre-recorded content. We’re heading in to a world now which, as AI becomes a platform for every industry, including the entertainment industry, we’re moving in to this era of dynamic content, non-linear storytelling, customer experiences that are being driven by us as individuals.

For that to happen, to be able to animate digital characters that are capable of human connection, human behaviour in real time, you actually have to create the concept of embodied cognition. You actually have to do what we’re doing, which is build brain models which enables our digital characters to dynamically respond interactively in real time and be animated completely autonomously.

And so it’s a big shift in terms of the way we think about bringing digital characters to life, bringing AI to life. We see it as being critically important because if, as humans, we’re going to spend more and more of our time interacting with machines, machines of all different types and flavours and varieties, we’re going to have to find ways to interact with them in a way that we can build trust, build relationships. We think that’s going to be a really, really important part of what we call the next era of the human race. Which, if you think about where we’ve come from over the last 100 years for example, the amazing things that we’ve created in the last 100 years have come as a result of humans cooperating and working together with other humans.

This next century, of course we’re going to have continue to cooperate and work together as human beings, but we’ve now got another big contributor, and the other machines that we create. So this next era could well be defined by the way in which we cooperate with and work with machines. We see ourselves as providing a platform for human-machine cooperation.

What sort of timeframe do you imagine we’ll experience this next evolution?

It’s early days at this point in time. Everybody’s talking about artificial intelligence, there’s lots of hype. If I asked you a question, what was the seminal event for artificial intelligence last year?

For me and for most people, my perception of the seminal event for artificial intelligence last year was Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo project. There we had their deep learning system, learning a new game – a game most of us had never heard of, most of us have never played – they created this event where deep learning, machine learning has crossed a threshold of reality. It’s won a game played by not many people. And yes, it was an event in its own right but AI in real life is still in its very, very early days.

The thing with artificial intelligence unlike many of the technologies that you and I have seen evolve, like the smartphone has over the last 10 years become a bigger and bigger part of our lives and the way in which we use it and the way in which we interact with people.

So that’s what I would call an incremental technology. The power and the potential of artificial intelligence is this concept of exponentiality and when you start applying it to industries, companies that experiment early, invest early, use early, could be creating the platform for a level of competitive advantage that those that delay or wait, don’t have.

AI’s going to be exponential. We’re going to see, in terms of what we’re doing and adoption of our technology, we’re going to see that increase quite quickly over the next five years. But after the three to five year point, there’s going to be huge inflection points.

We can envisage an era in maybe three to five years’ time where everyone in the world will be able to build their digital human, and train that digital human and have their digital human. Maybe we’ll have more than one. You might want a 20 year old version of yourself, a 30 year old version of yourself and a version of yourself today, or whatever.

Our view of it is this is not just about creating brands spokespeople and this will become a very, very ubiquitous technology. Just before Christmas we announced a new platform we call Digital DNA™. We built 15-odd digital humans based on the real life likeness of people, and we create some of the most high quality digital human-like characters in the world, outside of Hollywood certainly. That takes us, at the moment, about 12 weeks to do each one.

We’ve now built technology where we can take what we call the Digital DNA™, and we can blend the elements, the facial elements of those 15 digital humans that we’ve captured to deliver what you’d call synthetic digital humans. They’re not based on the real life likeness of anybody, but you can literally create them and bring them to life in minutes for almost zero incremental cost. So one vision of that future is we’re creating a set of tools which we’ll be able to give to everybody and anybody to build their digital humans.

And they’ll go and create more DNA.

They will go out and create those digital humans and in our business model, as we make money, when you want to plug them in to our brand models, into our animation engine so that they can interact in the real world on your behalf. So that’s the way we’re thinking about the future. It’s a very, very ubiquitous technology. A very, very, ubiquitous platform.

How do you quantify emotional response and intelligence? How do you create emotional connections?

We’re sitting here interacting. As human beings, we’re actually wired for face-to-face interaction, we form relationships, we form trust, and we form emotional connections on a face-to-face basis – that’s the way we work. The way our digital humans work, Mark and our team of researchers have actually built models of different aspects of the human brain. So they have an emotion system that uses the perception system that they’ve created to be able to perceive and analyse emotion. To be able to respond through the generation of virtual neurotransmitters, so our digital humans, through their brain models, have the concepts of virtual oxytocin and virtual dopamine.

If I smile at you in our conversation, unless you override it, your brain’s going to tell you to smile back at me, and your brain’s going to send chemicals to your nerves and your nerves are going to cause the muscles on your face to smile. That’s the way your brain is wired and that’s the way you express emotion, and our digital humans do that in exactly the same way. They have a perception system, they have an emotion system, they have virtual neurotransmitters which control their brain chemicals, which sends signals to their digital nerves, which in turn animate the digital muscles in their faces and, if you’ve seen any of our recent work with our research platform, they now have a full body. It has arms and legs which it can walk, it can animate in the world.

And while it’s not an immediate commercial requirement for a digital human to walk around on a flat screen, you can imagine what’s going to be possible in the world of VR and AR if we can create fully dynamic, fully interactive digital humans that react and respond to what’s happening in that moment, in that second.

Does this change the way that you interact with real people?

It’s kind of interesting. It certainly makes you think more about the way in which we connect as human beings. It makes you think about what makes us unique as human beings. Because at the end of the day, that’s what drives us as an organisation, that’s what drives our researchers, our engineers, our artists. We’re all exploring this concept of how do we create the most amazing connections between the digital humans that we’re creating and real people.

How can we put them to work and why does that make an incredibly meaningful difference in the lives of as many people as we possibly can? Yeah, we actually do spend more time thinking about that, when you’re working in technology. I’ve had a long career in different start-ups with different technologies. Actually getting the time to think about the psychology, the neuroscience, the anthropology; these are incredibly fascinating fields to get the opportunity to spend a whole bunch of time in and figure out how we make them work in the real world.

It must be mind-boggling as well, even in terms of cultural nuances. In say Pacific Island cultures it’s often that younger children will look down, not make direct eye contact as a sign of respect. In other cultures, that’s seen as being rude.

So when you stop and think about this for a second, the digital humans we create using our Digital DNA™ technology, that’s just how they look and how their muscles move. But we actually also have to capture the personality or create the personality. We actually have to build voices which they can speak with and that might be in different languages; it might be English, it might be Japanese, it might be Mandarin, it might be German. Because part of creating these personal customer experiences is about how you do that.

So, it’s not just about creating the look, it’s about how you create that personality. We have some amazing new projects rolling out in Japan and China in the not too distant future. You just raised the culture thing. So as you move round the world and start building solutions for customers in different parts of the world, the way in which human beings connect emotionally is impacted. Not just by the way they sound and the way they speak, but the culture with which they live in. So these are all parts that we have to integrate into what we think about as an organisation.

It’s not just about having a digital human that can speak multiple languages, it’s thinking about the way you create an emotional connection with a customer which might work in New York, but it’s not going to work in Tokyo or in Beijing. There are going to be these cultural variations that we need to understand.

The gaming world has really come leaps and bounds, not only in terms of the graphics, but also in respect to storytelling and even cinematic and emotional journeys that you’re going on as a player. I imaging that you could take this to another level even. You create a sandbox, you create this environment, you create some elements and character motivations and it almost starts creating a story in itself.

One of the things I often speak about is the application of Varian’s rule, so Hal Varian the Chief Economist of Google says you can predict the future based on what wealthy people have today. In the banking industry today, if you’re a wealthy businessperson, you get a private banker and that private banker gives you personal service and access to specialised knowledge. Imagine a future where using our technology, you could create a private banker for every single one of your customers. As an example, that’s a customer experience journey we’re going on with customers like the Royal Bank of Scotland and ANZ Bank here.

Think of having a digital private banker as we move forward in to the future. Not all the component parts are there, but imagine a world in the future where you can talk to them, like a financial adviser and a financial companion. You can consult with them directly about major purchases, mortgages and feel like you’re getting incredibly personalised service through an incredibly personalised interaction. This is the future of customer experience. This is the future of consumer experience.

At the moment, we’re working with a couple of the bigger celebrities on the planet and looking at the future of digital fan engagement. Imagine being able to talk, have a conversation with your favourite musician or your kids being able to have a conversation with their favourite football player or rugby player, being able to have that direct, what feels like personalised, one-on-one experience.

Now this is the exciting potential and possibilities, because, when you look at what the movie industry and the gaming industry are achieving at the moment, it’s still what we’d call linear storytelling. It’s still based on pre-recorded content. Games engines have stories on rails so there are always multiple ways through any one level. There’s multiple directions you can go; if it’s a hit game that millions and millions of people like, they continue to add new content, new stories on an ongoing basis. So you’re always discovering, you’re always interacting, but it’s still linear storytelling.

It’s a whole other level to have non-player character reacting to a player completely unscripted.

It’s a completely different future. And then you start pulling all of these technology components together; artificial intelligence, AR [augmented reality] and VR [virtual reality] and then you start saying, well what happens to the future of sport? The professional sporting industry has been on this massive growth curve, fuelled by growing television licensing fees and we are starting to see signs that maybe that’s going to come to an end soon.

Those sports franchises, those sports industries are going to have to say, ‘Well, how do we start engaging our fans digitally?’

But imagine a world in the future where you can literally attend the game from your living room via AR and VR. You can choose where you stand in the stadium, you could choose to stand on the side-line. Maybe you can stand next to the coach and ask the digital coach questions about what’s going on in the field at any point in time.

Now, this is not five years away, this could be 10 years away. But these are the sorts of scenarios that you can start to imagine as these big technologies start to come together and create the future.

So, the research that we’re doing is world-leading to the best of our knowledge and we work with some of the biggest companies in the world, the Googles and the Amazons of this world. Nobody has built brain models, connected them with neural networks to create this concept of, or the science we referred to as, embodied cognition. We’re the first people to do it. This is the culmination of Mark’s incredible research.

As a business partner, it’s my privilege to work alongside Mark and figure out how we create a business, how we make a difference with his amazing technology. It’s quite an amazing partnership; he’s creating this amazing technology, I get to figure out how to create an amazing business around it. And yeah, we’re having a lot of fun doing that together.

There are so many different potential executions. Is it part of your role to try and keep some focus?

Yeah, absolutely. We’re keeping a really tight focus. We want to work with people, with leaders, with CEO’s, with industry leaders who want to be the first in the world to experiment and use and innovate with this technology. So we’ve got a very, very tight focus around a very, very specific group of people at the moment.

This is not technology that’s for everybody today. We’re planning for that future where by producing these toolsets, which we’ll be able to give away, and have people create this amazing technology for themselves. The really complex stuff; our brain models, our animation platform will do all the heavy lifting in the future. It couldn’t be a more creative, fun opportunity to spend your time doing. I get up in the morning and literally pinch myself that this is called work. I’m having so much fun, we’re having so much fun.

From an investor perspective, is there pressure at the moment for revenue or is everyone focused on the future?

We’re a venture funded company. We’ve been fortunate to attract some of the leading early stage investors in artificial intelligence in the world, with Horizons Ventures who led our series A round. They backed the Siri team when it was formed. When the Siri team left Apple and created Viv, they backed the Viv team. They were early investors in a whole range of early stage AI companies. Having investors like that who are incredibly supportive is fantastic, but when you’re creating a business like this out of the amazing technology, this is about continuing to hit milestones and continuing to hit proof points which demonstrate the potential value of the endeavour. So yeah, you always feel the pressure.

Our revenues and the sorts of customers that we’re working with, the sorts of revenues we’re generating, the sorts of the customers that are signing up for long-term contracts, some of the amazing projects that we’re now working on with some of the biggest and most influential companies in the world, means I’m pretty happy with where we’re at in terms of turning the technology into a valuable business going forward.

But, that’s certainly something you can never let slip too far from the back of your mind. As a company, we’re close to 100 people now. That takes a fair amount of capital to keep the lights on and keep things moving forward. We have offices in LA, San Francisco, New York, London, Tokyo, we’re adding a couple more; China and Singapore are likely to be next. Melbourne’s another location we established last year, so this is something that you keep running faster and faster.

Going back to what formed you and what excited your brain as you were growing up, what formed those neuropathways?

I’m a university dropout, so I left high school, went to university, didn’t really like it and was lucky enough to fall into what today you’d call an internship with a guy called Bill Foreman, from a company called Trigon Plastics. Bill, when I think back on it, was one of New Zealand’s earliest high tech entrepreneurs. He was reinventing the packaging industry from the ground up with incredible engineering innovation. So at a very, very young age Bill took me under his wing, gave me the opportunity in my late teens to participate in Board meetings and strategy and international growth.

So Bill inspired me to become an entrepreneur. Bill inspired me, got me focused and got me passionate about competing and winning on the international stage. Bill got me hooked on technology when he literally threw me the keys to his multimillion dollar computer implementation, and said ‘These scientists can’t work it out. You understand my business, you see if you can make this damn computer work for me’. And that’s really where my journey started.

I love taking complex technology and figuring out how to break it down in to value blocks and value components and then going out and figuring out what works and what doesn’t work. I love competing on the international stage. I’ve spent most of my life wandering around the world working on different entrepreneurial projects, trying to figure out different markets. I’ve got plenty of scar tissue, plenty of failures to look back on, but at the moment, I still get a huge buzz out of it.

Often you will talk to New Zealand entrepreneurs and they’ll say that we don’t tend to take failure that well here. Overseas, it’s seen almost as a badge of honour.

Failure is a fact of life if you’re an entrepreneur. If you’re not failing, you’re probably not taking enough risks, you’re probably not getting close enough to realising your potential. As kids, we learn by failing and failing repeatedly, so whether it’s part of New Zealand culture, I think New Zealand culture is changing. I think our entrepreneurial community is growing up and our kids are becoming much more inspired by the entrepreneurial journey and learning to accept failure, failing fast and learning quickly as part of that process.

There’s a difference between doing it in New Zealand and doing it on the international stage. And that’s a factor of numbers, it’s a factor of complexity and sophistication of markets. For me, trying to figure how to win deals in New Zealand doesn’t spin my dials, and in reality, doesn’t necessarily help you. It’s not necessarily going to help you to win in a large and sophisticated and complex market like the US, where you can name any field you like and there’ll be dozens and dozens of competitors. All of them will be better funded than most New Zealand start-ups.

Now, it doesn’t mean you can’t compete but it means you still need to figure out what your unique differentiation is and how you’re going to compete. When you’re competing on a global stage, as we see time and time again, unless you are incredibly smart and incredibly committed, you won’t win. All of those things are magnified in a place like the United States and a place like Silicon Valley and a place like New York City. Tech world has historically always been incredibly US-centric. If you think about the world of artificial intelligence, there’s a second major superpower in the AI world and that’s called China.

A company like ours, creating what we believe are some of the fundamental science and fundamental building blocks for the future of artificial intelligence, you cannot ignore the Chinese market. China has many huge advantages in many respects to the way in which they can build an AI industry over the US. So you can’t just look at the US, you actually have to look to the way in which AI is developing in China.

China has many industries that didn’t grow up over the last 20 years. So, as they’ve got this growing middle class and they have to develop new healthcare and new educational services, they’re in a position for their industries to apply artificial intelligence and leapfrog what’s going on in other parts of the world. I was in Beijing last year and I didn’t see anybody use cash, I didn’t see anybody use a credit card. They live in WeChat. It’s just part of day-to-day life. We talk about how New Zealand was an earlier adopter with EFTPOS and what have you but, other than getting my credit card out at the hotel, it was the first and last time I saw anything that resembled the way in which we pay for stuff here, or in the Western world. The world of AI’s an incredible place when you consider even just the dynamics of that market tension between US and China. It is becoming regarded as a critical technology race.

Beyond that, are there other benefits to being a start-up in New Zealand with an overseas focus as well?

The good news is we’re a long way away from anywhere, and the bad news is we’re a long way away from anywhere. There are enormous challenges in building high tech and deep research companies, like ourselves when you’re a long way away from pools of very, very deep labour. As a company, we’re a spin out of the University of Auckland; we have a very high percentage of research staff, and a large number of professors; and PhDs on our team and that enables us to quickly scale to the point that we are now.

But to continue to scale this company, there isn’t the depth of very, very specialised talent in this market and that represents the challenge. It means you start having to think about distributing different parts of your organisation at a much earlier point in your development, and that’s another challenge that we have to overcome in terms of supporting. We have researchers, key researchers now dotting a number of different places around the globe, because that’s where we can find the talent, that’s where we can locate the talent, that’s going to be an increasing part of it.

We’ve recently brought on very senior executives in areas like Customer Success and Product, all of which have been fulfilled out of the US, attracting very experienced and senior people. And one of the challenges is, do you put those people close to your research team, or do you put them close to the market? Ultimately, you succeed or fail in the market, so my view on that is you actually have to put them close to the market. They have to be close and understand the way in which the market and the ecosystem and the structures and the economics and the competition are evolving, if you’re going to compete and be successful.

So, lots of challenges for companies growing up and trying to scale, like me. You showed me one of your magazines with Peter Beck on the front; he’s scaled a company and he had to build a significant presence in the United States where he has access to the talent pool and the proximity of some of his key customer markets as well. But they are some of the challenges if you are in an industry or you’re building a business which is based on complex science, deep science and deep research. Building out valuable pattern portfolios and then figuring out how to apply it in the markets that you choose to compete in.

In terms of the US VC side of things, you’ve got an incredible track record and I’m sure that you’ve got those connections there. Would they normally look at the New Zealand market and take us seriously?

Yeah, absolutely. When I first started off a long, long time ago travelling to and living in the US, rule number one of Sandhill Road was if you can’t drive to it, don’t invest in it. So, 20 years ago, getting a US VC to invest in a New Zealand company was never going to happen. That’s not the case today; venture capital is frictionless. Venture capital will find the best businesses in the world to invest in the best technologies. The best IP in the world, the best research in the world, to invest quite frictionlessly, no matter where the company in the world is. So you see US VC’s investing in Australia and New Zealand and Asia and they really take a very, very global view of ‘where can we find the best businesses?’

In my view, New Zealand probably punches above its weight in terms of its ability to attract world class VC’s. Because here’s the simple reality of the start-up world: not everybody gets to raise money. In Silicon Valley, more start-ups fail than get funded. The sorts of VC numbers would mean only a handful of companies are getting funded; a single VC fund will only make a handful of investments in a year. If you look over the last few years, something like five new companies a year attract US VC’s or top tier international investors. Those numbers feel like we’re out-performing in some respects.

I think more discussion needs to be had about we can fundamentally change the quality of the start-ups that we’re developing to attract more VC funding in to this country. VC’s increasingly are looking for different types of investments. If you look at the sorts of companies that do attract venture funding from the US from the top tier investors, it tends to be companies that have deep research and deep science behind them. Like the guys from Rocket Lab, like the work that we’re doing, like the guys from LanzaTech, for example.

I look at the world of venture capital and say ‘if your company’s good enough, you’ll attract great investors’. I have been doing this for a long time, so I’ve met a lot of people, I’ve got some great networks around the world which obviously helps.

When you’re talking about improving the quality of start-ups, are you talking incubators, are you talking more education?

No, I think we’ve tried and we’ve built many of these systems over the last 10 years, and they’ve all made a difference. I think the next steps that we take are harder, because I think it’s like most things in life, you can get some quick wins relatively easy. The next level of growth can take a decade, so my opinions on this – and I’m relatively upfront about it – we need more of what I call bigger research, deep science-based technology businesses and franchises. It’s absolutely critical to the future of our technology industry.

We can be very proud of the growth that we’ve had in our technology industry over the last 10 years, but one of the big challenges is a lot of that technology runs the risk of being commoditised very quickly over the next 10 years. We have some very large technology companies, some of them are service-based, some of them are engineering-based and if we’re going to build a sustainable and a valuable technology industry, research and science are going to be key parts to that. And there’s some fundamental challenges we face from a research and science perspective. Many of the amazing researchers and scientists that built their franchises in the 60’s and 70’s, they getting near the end of their natural life. Guys like Sir Richard Faull. Obviously, we’ve lost guys like Sir Paul Callaghan already.

We have some amazing researchers, but here’s the thing we need to think about: how do we continue their work? How do we protect those research franchises, how do we build commercialisation and ecosystems around those research franchises? Because the long-term challenge is the kids that are growing up today that want to study and want to get into research, our smartest kids don’t have to go to the local university anymore. They can go to MIT, they can go to Harvard, they can go to Stanford, they can go to Cambridge, they can go to Oxford. And if kids who go out and study in those places and decide on research careers, the sort of funding they will find in those locations, they’re not going to come home at any time soon.

So, I hope like hell I’m wrong. I love to be wrong, particularly on this one. The hollowing out of the future of our ability to do core research and science-based technology, I think is one of the scariest concepts for us and our technology industry going forward in the future. I raise it not to piss people off or annoy people, I raise it because I want people to think about it. Because if we don’t think about it and start thinking about what we could be doing to protect and save it now, it could be gone forever. Once again, I hope it’s not. I hope I’m wrong.

Soul Machines is a beautiful example of how university-based research can work with business and investments.

My last company, Power-by-Proxi, was also a technology spinout of Auckland University. When I came back to New Zealand from my last overseas stint, I got interested in the commercialisation of science and technology. We do have some great research franchises and some amazing researchers buried in our universities.

For example, the University of Auckland have come a long way in the last 10 years. But for me, I’m not saying that all technology companies should come out of universities, but if we look at some of the hugely valuable companies that are being created at their core, is research and science.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

My best piece of advice is, probably around persistence. Nothing is easy, nothing’s simple. To create anything valuable and meaningful in life is always going to require a level of hard work, a level of persistence, a level of making mistakes, getting back up, dusting yourself off, figuring out what you needed to learn and continuing on. Yeah, probably the single biggest piece of advice I ever got was don’t give up; you’ve got to keep pushing and pushing and waiting for that breakthrough to come.