Bruce Hunt – The Backlands of New Zealand

Artist and photographer, Bruce Hunt, has been exploring New Zealand’s unique landscapes for over 40 years, walking the ridgelines of our rugged back-country and bringing back images of its rippling form.

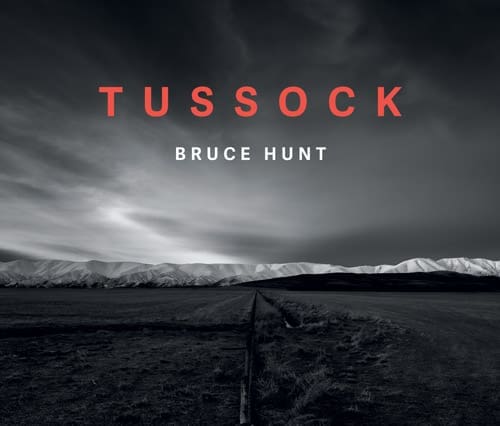

His new book “Tussock” is a culmination of that work, so we took some time to have a chat about his process, his journey and how we might protect this beautiful country of ours.

These are incredible shots, they’ve made me see Aotearoa in a new way. What initially drew you to these landscapes 40 years ago?

Thank you. My earliest vivid memories of the Southern landscape were of the immense scale. My father presented my first camera loaded with black & white film on a family jaunt around the South Island when I was about 9 years old and it was the drive to Milford Sound and the breathtaking scale of the towering mountains of Fiordland and the Southern Alps that inspired awe in a boy growing up in Wellington.

Later, at the completion of college, the draw of the high country was irresistible for an aspiring landscape painter, so I headed south to explore Central Otago and the Mackenzie Country. They were quiet, empty places then, the landscape and its unique atmosphere was all-encompassing and human encroachment sparse. I travelled alone to know solitude with a view to making pictures that reflected my viewpoint at that time in my life.

Life as an artist is about challenging doubt and uncertainty and so these landscapes triggered a range of emotions in me that informed my art.

I feel a certain unease when venturing deep into them, a tension born out of some danger and insignificance, but also the physical challenge and excitement of exploring unknown territory.

How do you find the locations? What was your gameplan?

I like to study topographical maps and plan picture-making expeditions based on curiosity and anticipation of what I might find, although my locations are very specific and few. I then set out to create networks of viewpoints over a period of time. For instance, my network of viewpoints in the Lindis region is extensive as I have been returning over many years and there are not many ridgelines I haven’t traversed.

Over the years, I have discovered ‘pockets’ within broader landscapes that I’m compelled to return to over and over. These locations have certain indefinable characteristics that draw me back to make paintings and photographs but generally, they are lonely places, thick with atmosphere with visually fascinating topography and patterns.

Initially, my viewpoint was ground level, then I started to climb to see what was over the other side of a ridge or peak. This opened up the topography and patterns of a place because I was elevated and looking down into the landscape, and so I also became interested in the awesome forces that had created the landscape and its forms and rhythms. The physical challenge of venturing deep into these places and experiencing what it feels like under my feet is vital to my intimate knowledge of the landscape and my subjects.

As the book developed, I was fortunate to photograph from a helicopter. These are the ‘hawk’s eye’ views that really emphasis the geomorphology— the patterns created by glacial movement, rivers and the tectonic process.

If people wanted to follow in your footsteps to get a taste of this landscape, where would you suggest they head?

Many remote territories that have been opened up to the public in recent years by DOC.

In the Lindis region, the Dromedary Hill track is a great challenge and opens up the backcountry of the Lindis. The Oteake Conservation Park encompassing the Hawkdun Range, The Danseys and Mount St. Bathans and the historic Dunstan Trail behind the Rock and Pillar Range west of Dunedin traverses some superb tussock country. The Two Thumb Track east of Lake Tekapo explores some fantastic geological landforms mainly formed by glacial activity and deposits. These are some of my favourite and well-explored locations.

You sometimes spend a while out in the Backlands. What’s your longest stretch?

In my younger days, I often spent calm nights under the stars amongst the tussock high on a ridge or under a rocky outcrop. Nowadays, I mostly base myself in locations where I can venture out on day trips and return to base and regroup or get back to my vehicle where I may sleep for several nights. I stayed in a fishing crib next to the Waitaki River back in the 80s for six months and explored the surrounding mountains. Naseby was another base for long stretches exploring the surrounding hill country. I also like to base at Twizel to explore the Mackenzie Basin.

The body suffers these days after long days slogging up and down brutally steep slopes but that physical, up close understanding of a place is so important to my work.

What do you shoot on, and what gear do you find you always take with you?

I’m not a technical photographer, rather an instinctive picture maker.

I travel light in the hills with a DSLR and if on a longish trip, I also carry a smaller mirrorless camera with a single prime lens. But mostly it’s just a small pack with essentials, warm clothing and one camera.

Before digital, my photographs were made with a Nikon F2 and an F3. I liked the feel of them—very robust and reliable cameras.Now I use a Nikon D750 or D800, usually with a 24-70mm lens or a 35mm prime.

In busy ‘peopled’ situations, I use a Lumix GX85, a small mirrorless camera that seems to work quite well in close and busy events.

Many of the situations I encountered in Brazil (religious festivals, Carnival, markets, funerals and street work, etc) required an unobtrusive, easily manoeuvered camera and I used a Lumix GX7 with a 15mm (35mm) lens. My cameras suffered greatly in the hot and dusty conditions of the northeast and they took many a tumble.

Have you seen any change in the landscape since you first started out?

There has been a very distinct expansion of pastoralism into the high country. Our classic high country regions are becoming a lot greener and the Mackenzie Basin has been transformed between Omarama and Twizel, not only from the development of dairy farms but the expansion of housing out into the plain around Twizel. Our classic and once unique views of high country plain with the backdrop of big snow-clad mountains have been severely disturbed by farming equipment and shiny iron roofs.

When you were in Brazil, how did the geography compare?

I lived in Brazil with my Brazilian partner from 2012-2016— a very exciting time for Brazil hosting the World Cup and the Olympics. Our travels around the country were extensive as I became interested in photographing with a documentary flavour, aspects of Brazilian culture and industry. The sugar cane and coffee industries, Iemanjá religious festivities in Bahia, Carnival, the Vaqeuiros (Brazilian cowboys) and graffiti culture in Sao Paulo became targets for my camera. It was a fascinating time trying to understand the culture through the lens of the camera. So my photography focused on the Brazilian drama of life played out on the streets rather than the landscape.

However, one of the greatest experiences for me was living for long periods in the birthplace of my partner in a small rural town in the hot and arid northeast state of Piaui. My photography here was very personal and intimate and I became part of the fabric of a very different life. It was not easy at times as the local critters came visiting at night—scorpions, tarantulas and on one occasion a snake in bed made for exciting times.

The landscape and the people here, come together to create a strange harmony. The terrain feels ancient, is red with monolithic rock outcrops and covered in brittle trees. The soil on the flatlands is rich and a river provides water to grow sugar cane and various staple crops and run cattle.

Brazil is a huge country that crosses many latitudes so certain parts of southern Brazil and Sao Paulo state very much resemble the landscape in the North Island.

The crop belt through the central interior is vast and flat and in the north, the landscape is arid and diverse—and of course, the famous beaches and coastline are very beautiful and varied.

Are you happy with what you achieved there?

I was fortunate to compile an extensive body of photographic work in Brazil and this is evolving into a book. I was able to point my camera at an enigmatic and boisterous culture in all its diverse forms. Over a day, you witness the very best of human nature but also great dysfunction and unfairness and the very worst of human nature. Such is the fascinating Brazilian drama of life.

Most of the work is in black and white and I think, because of the length of time spent there, it offers a unique and intimate viewpoint into a brilliant country and people.

It was never easy making pictures in Brazil so the resulting imagery does give me a great sense of achievement.

When Covid clears up, do you have plans on heading anywhere else?

Generally, I’ve travelled to countries where my curiosity has led me, like Japan and the USA. I would love to explore South America further. It’s a raw and diverse part of the world where you are constantly surprised. But my work is born out of personal connection to place so a return to Brazil would be high on my list.

What do you think we can do to conserve these landscapes?

I think there is a growing awareness that our significant and unique natural landscapes need conservation for a number of reasons. Vast stretches of open high-country tussock are important for water retention, erosion control and places where unique flora and fauna reside and flourish. They aren’t empty places, ripe for transformation to fuel our evolving economy. Sometimes it seems they can be easy targets for development because they are considered unpeopled and remote yet accessible and not that far from cities. Such is the nature of the New Zealand geography.

As Sir Alan Mark so succinctly states in the foreword to Tussock;

“There remains a unique and intangible quality to these grasslands that cannot be measured scientifically or economically, and that is the ability of these landscapes to hold us in their thrall.”

What do you hope people get out of your work?

I’ve photographed in black and white as a means to shape reality, create atmosphere and mystery and highlight the wonderfully muscular forms and textures so distinct to our high country. Ultimately, I want to convey my personal sense of these important places and to present an alternative viewpoint not usually conveyed in New Zealand landscape imagery. I think the monochrome image does this in a unique way.

I also want to encourage viewers to explore our backlands, to look with different eyes and to remember the importance of our tussock high country to all of us as New Zealanders.

Tussock by Bruce Hunt, photography by Bruce Hunt, published by Bateman Books, RRP$69.99

Now available. To purchase, check your local bookstore or any online retailers.