Dancing Along the Narrative

To tell any personal story, one must have a starting and an ending point. For anyone who knows the journey of a performer, it is where the performer is headed that counts the most and if the story, told right, can be enhanced. To learn is one thing, but to show such learning on stage takes an enormous amount of work and talent.

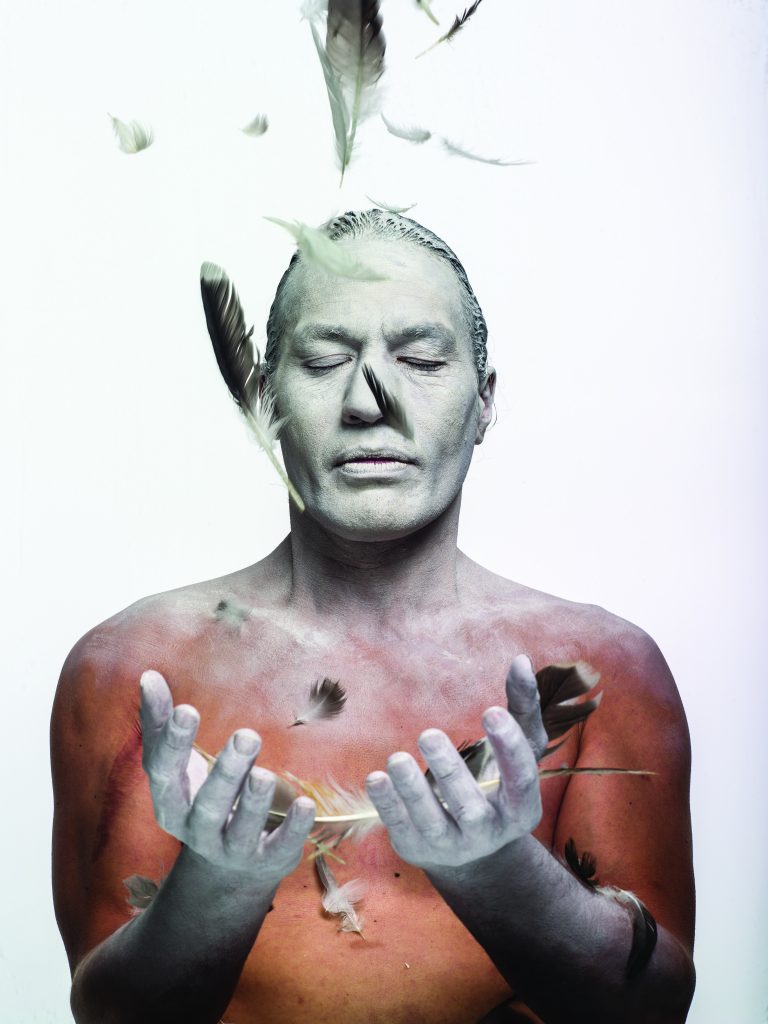

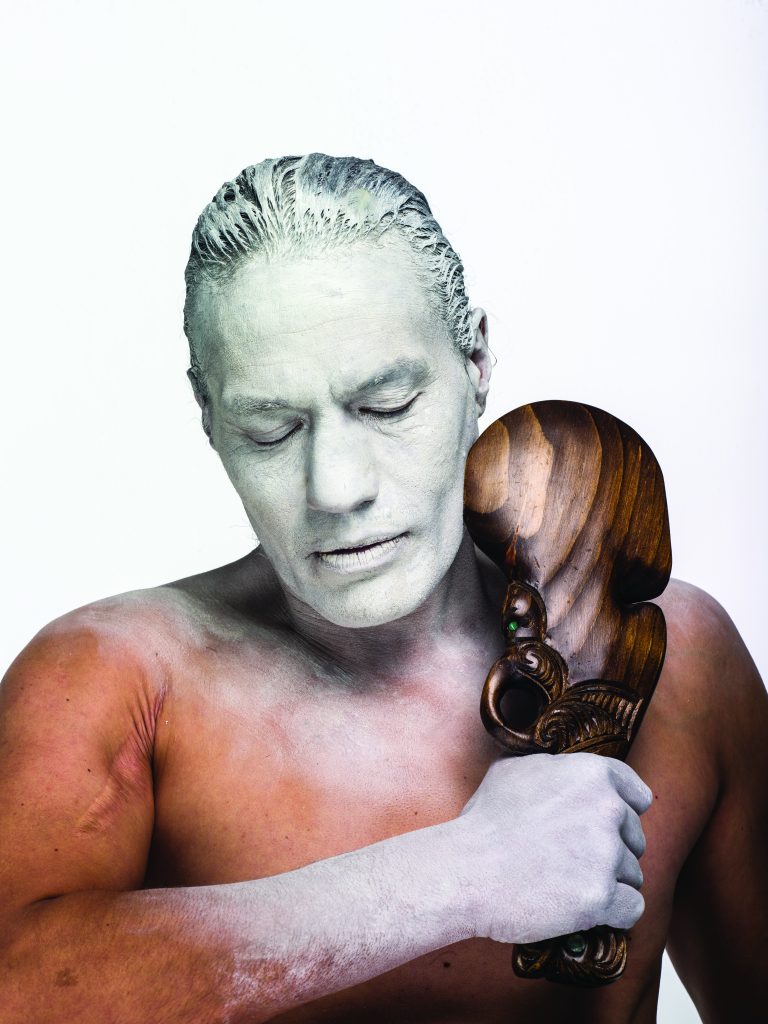

Paraplegic dancer, Rodney Bell, knows this journey all too well. He was born in Te Kuiti and has grown to be an internationally-renowned, award-winning dancer. He uses his past to inspire his present – movements and storytelling portray as his art. His solo show, Meremere, has been touring nationally and internationally since 2016 and uses many different elements of his journey to influence and teach.

Disability, in honesty, is an element in Rodney’s dances that he can’t run from. He’s bound to his wheelchair to live and move, but never, it seems, does it get in the way of him and his hunger to create. As you watch him perform, it seems like the wheelchair disappears and he is floating, or flying, using metal wings. He never asked for this type of flight, but he’s gloriously soaring with what he’s got. The man’s life has been full of stories. In Meremere, he tells it true. His Māori heritage, for example, or the motorbike accident he suffered in 1991 that left him wheelchair dependent, or even his time spent living on the streets of San Francisco.

As we talked to each other, Rodney and I chatted about how he’s grown as a performer, and how his story has grown too. How, in essence, he plays as a vessel floating on a dark stage that, as the crew deconstructs the set and moves it across the country to the next theatre or space, so does he. He too is broken down and rebuilt stronger – a starting and an ending. Every movement he gives in his dancing is powered by his story and energy. It unfolds onto the stage in bursts and raptures, with Rodney’s shadow spilling out behind him as he looks forward to the light.

How do you define determination?

I think determination is driven from the community. Having the will to do something, but then having the support around you to encourage it. It starts from one place, but then it’s developed by a whanau. It’s the mana.

You suffered a motorbike accident in 1991. Can you tell us a bit about it?

That’s where I acquired my disability. I was drunk at the time. I’ve been told lots of different stories about what actually went on, so, over the years, I’ve had to piece together my narrative off other people’s energies. At that time, it was as though I’d been broken. I call it a gift, now. I’ve been given this gift. No, it wasn’t given in a Christmas wrapping or on my birthday, it was given in a way that was full of challenges and obstacles. It was wrapped with tornados inside a storm.

I was very fortunate, though. I look at what happened as being all my lived experiences clustering together to help me, like the way I’ve been brought up – humbly – by a loving whanau. All those things really grounded me, and I held those tools. Tools; you wonder what they’re for sometimes. But when something happens in your life, like an accident, you are prepared so much for it.

My family had been broken as well, and I was being quite selfish dealing with it. I had to stream my own emotions and channel through that. I sort of forgot about the whanau at one point. I forgot about the pain and suffering they were going through. Selfish, I know. If I could go back in time, I wish that I had been more supportive to them.

I was in the Spinal Unit with others that are higher needs than me, and that – to be honest – gave me hope. It wasn’t because I compared myself to them. Hell, so many of them had a lot more strength than me at times. It was because we learned to share and we leaned on each other. That was an important part of my rehabilitation. I also had very experienced nurses and they were elderly, so they had lived experiences with spinal injuries, so they gave encouragement. I did push against it, but now I feel that that’s what I needed at the time. It really supported me without even realising. In a way that actually has made me a very strong person.

What does disability mean to you?

I was brought up with a couple of disabled uncles and aunties, and I’d always been taught to treat them the same. I knew they had needs and didn’t operate the same as able-bodied people. But I never regarded them as ‘disabled’, I saw them as just ‘different’. So when I acquired my disability, I was like ‘wow, the whole world is different!’ It just made me realise what I had and to make the most out of it. It opened my eyes. Disability is just ‘different’ opportunity.

What first attracted you to dancing?

Dance found me through the energy I had. Catherine Chappell (MNZM, founder of Touch Compass) enlightened me. She planted the seed in me and nurtured it until I got more independent in dance. I’m forever grateful to her for that.

In 2012, you lived years homeless in San Francisco…

Yes, I was going through a rough patch, mentally, at that time. I wasn’t thinking straight and I was going against the grain and trying to find my identity during that time, in relation to dancing in America and being away from my family for so long. All my sacrifice seemed to flood to the forefront, what I was actually doing there. That energy was reflected on my opportunity in Axis Dance Company. I started being a rebel and I ended up on the street all of a sudden. I thought, then, that that came part and parcel with my own journey. There was nothing that put me there, other than myself. I then saw that as an opportunity.

‘Alright,’ I thought. ‘I need to get myself out of this.’ I couldn’t lean on anybody. I found with the street that you have to go into survival mode. You’ve got no time to meditate and sit with your mind. It’s just yourself and you need the essentials. Food, water, shelter. When I say water, that means bathing as well, not just to drink, and toileting. That was a huge for me. Having my disability, those three things consumed all of my time and my energy. Finding places to use the toilet, and basic hygiene was just difficult. Time just flew by too, just flew by.

By the time I realised I was really stuck, I started getting energy again. I started looking after myself a bit better, and started to understand the culture of the streets. I understood. It’s a big theatre out there in such a different world, you’ve got to play your role somehow. It gave me a thicker skin. It opened my eyes to cultures and histories that are still alive. Like Silicon Valley, what technology is doing to San Francisco and money. How money separates communities. How I was invisible in comparison. I enjoyed that, though. People didn’t want to talk to me. Disabled and homeless. With disability, San Francisco is a very accessible city, but it’s grubby too. You’re always negotiating to survive.

Has that experience added to your performability?

Yes, definitely. Especially performing Meremere from those memories. I’m just so invested in this show and what it says about people, not just me. There are so many energies – and they come through quick. I want the dancing to be supported by the story, not the other way around. I want that kind of energy, in a way, to be respected and deserved. Yeah, the story is the main focus, but I want the memory and energy to be a channel or vessel. It’s cool, because at the end of the process, I’ve been able to step back and go ‘Wow, was that me? Did I really do that?’

There are also other voices to the performance. Other appreciations that the performance can enhance. Different energies. Seeing who they are and what they bring in the moment.

Tell us a bit about Meremere…

Meremere is an autobiographical work, created with MOTH (Movement of the Human) and directed by Malia Johnston. Meremere opens again at the end of the month in Nelson. It’s a work that we developed in 2016 and it went on to Q Theatre. It’s been a great journey. It’s been exhilarating for me, because it’s autobiographical work, so it’s bringing up the memories.

It’s also evolved, because it’s autobiographical. I’m able to recap things and fill in the gaps between each show. For instance, there was a year lapse and then it came back into fruition again in 2018. It was really nice to revisit, but things have changed in my life, which we added to the show. I love that about this work. Also, because the work is about some dark places in my life, I really enjoy the opportunity to revisit those memories from a different perspective.

It has such a beautiful team too. Eden Mulholland is the musician that sits downstage. There’s a strong connection there, throughout the work. Then there’s Rowan Pierce, who’s put a lot of AV throughout the work as well. The set (created by John Verryt) is quite cool. It’s got an interesting shape to it, and is quite easy to deconstruct and move. A revisiting of a story in a different place. We’ve spent a lot of time developing the work. Emma Willis was brought in as dramaturg, and Tui Matira Ranapiri-Ransfield as Māori dramaturg. It’s a real strong team of collaborators. We’ve had support from Creative New Zealand, too. A very fortunate possession. Going from disability to the streets and now having an acknowledgment in creating something.

How do you stay motivated?

I stay motivated by acknowledging the tools that I have. How I utilise and use that to help others. Through my lived experience, I’ve been able to acquire those tools to teach and be compassionate towards others. I’ve used them in disability situations and how I relate to discrimination and reactions of racism. I always look for opportunities to save a situation, rather than lose an opportunity. That’s motivating. I also get motivated by healthy living. I can tell that if I put too much of a bad thing into my body, obviously I’m going to react to it.

I like to work alongside Māori culture and teaching too. The lunar patterns, for example. The constellations. That’s how our energies, our journeys, are given to us. For instance, Matariki, meaning ‘the eyes of God’ and Tāwhirimātea, changing the wind. I don’t know about you, but I’ve been feeling really good lately. I care for the lunar cycle now. I look towards the Māori calender and if I am feeling kāhore (meaning not a good time), I will know why. Bad moods and lack of motivational energy – they’re not our fault. It’s all in the stars.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?

It was from my Dad, just before he died. He said ‘Don’t take advantage of anyone, son.’

I remember, I replied: ‘No, I won’t Dad.’

Rodney Bell heads on tour with Meremere from 26 July. Tickets available at www.movementofthehuman.com