Dr. Robot Will See You Now

Admittedly, going into any type of medical procedure is oftentimes a nerve-wracking experience, yet there is always the reassuring thought that you are in safe hands.

Imagine being wheeled into radical, intensive surgery and, staring up at the operating lights, you expect to meet the tender gaze of a caring surgeon. How you long to meet such tender eyes, just for that comfort that everything is going to be okay.

That aforementioned surgeon, you assume, would be a product of years at med-school, an expert in their field, a custodian of compassion, professionalism and integrity.

But what if that surgeon didn’t have ‘tender’ eyes? What if your surgeon doesn’t have any eyes at all?

Robot-assisted surgery is fast becoming a popular means of medical procedure around the world in many different ways. It seems that now in 2019, every bit of the human anatomy can be refigured, redesigned and recovered by robots.

In a recent article, written by the Robot Business Review, “more than 5,000 surgical robots were used in more than 1 million procedures worldwide in the last year”. The procedures ranged from orthopedics, general surgery, to rectal or colon, even to dental or hair transplants.

The craze behind robot-assisted surgeries started in 1985 when Vancouver-based biomedical engineer, Dr. James McEwen used the Anthrobot to manipulate a patient’s leg on demand. This was followed by another medical breakthrough in 1999, when American-based Intuitive Surgical launched the da Vinci Surgical System – the most commonly-known practice – which uses multiple controlled arms that utilize 3D visualisation.

It’s still being used widely today. According to a report penned by the company, at the end of 2017 Intuitive Surgical had sent out a total of 5,770 systems with 65 percent being in the United States. That in itself made a global revenue of $3.1 billion. It’s almost terrifying to think how much that number would have grown in two years.

Practicing General and Vocational Surgeon, Dr. Jamish Gandhi, knows all too well the benefits of this system. He is practiced in the da Vinci, mostly in its Xi model. The Xi model is its latest surgical system which specialises in minimally invasive surgery, designed with a slimmer boom-mounted arms, guided targeting and auxiliary technology.

“At the moment,” he says, as I ask him what robot-assisted surgery means, “robotic-assisted surgery entails the robot being on a platform next to the patient. The surgeon controls the robot. Basically, the movements are made by the surgeon and then they are conveyed to the robot which undertakes the procedure. There are multiple advantages, but it’s not like the robot is doing it by itself – not at the moment, anyway. We’ve got full-control of the robot.”

Robot-assisted surgery are actually split into three methods: supervisory-controlled systems, shared-control systems and telesurgical systems. These modes of procedure vary on the amount of assistance the surgeon is receiving from the machine. In the case of shared-controlled, for example, it requires minimal assistance from a machine, whereas the supervisory-controlled systems are.

These types of surgery, with world-leading names like Zeus, Aesop, and the aforementioned da Vinci, have revolutionized the way surgeons can be assisted in their processes. Google has got on board with their life-sciences division, Verily. Planned on a 2020 release, they are working in partnership with Johnson & Johnson’s Ethicon Endo Surgery to create a world-class surgical robot. Johnson & Johnson will provide the medical reassurance, and Google will deliver a networked software operating ecosystem that will utilise artificial intelligence, cloud computing and even apps beamed straight from a smartphone.

“The robotic platform allows humans to be slightly better,” Dr. Gandhi says on the balance of human and machine-based surgery. “The combination between the robot and the surgeon is better. You’ve got a great advantage in standard laparoscopy where you can use a 3D scope, but I that’s less common and not as good as da Vinci’s magnified view, where everything is zoomed in. When I was taught with a da Vinci, which was recently, it was like a driving instructor model, in terms of the other surgeons potentially hitting the break on the pedals and them having full control. My input would do nothing. If the surgeon wanted to do a dissection, they could electronically tell me exactly where to go. They could draw on their console which comes up on my console, and doesn’t disturb anyone else’s view of the operation.”

Robotic surgery has also touched the world of angioplasty with the CorPath too. Founded by Corindus Vascular Robotics, Inc., it is a soon to be leading member in vascular interventions. It is the first ever FDA-cleared medical robotic device for percutaneous coronary and percutaneous vascular procedures. It is designed to allow robot-assisted coronary guide wires and balloon catheters to be placed with little intrusion. There are two factors to mention when describing the CortPath System. It includes a Bedside Unit, which technically is the heart of the machine, and its Interventional Cockpit. In the Cockpit, a simple-to-use control console provides real-time motion for Dr. Robot to work its magic.

In the orthepedic arena, MAKO Surgical have recently released its RIO Robotic Arm Interactive Orthopedic System and the RESTORIS MCK MultiCompartmental Knee System that completely refigures and develops bone and tissue for knee resurfacing. It uses CT-derived 3D modelling to “capture” the “full flexion and extension”.

As noted before, with the inclusion of artificial intelligence and machine-learning algorithms, cases can be stored in the cloud help to improve systems over time. In Spain earlier this year, a surgeon performed the first surgery ever using 5G-powered telemonitored operation on a patient five kilometres from his controlling unit. The surgeon, Dr. Antonio de Lacy, gave real-time guidance to another team in Barcelona. The process was for the Mobile World Congress and Chair Executive officer of GSMA, John Hoffman, who said that it “is truly revolutionary and just one of the benefits that 5G will bring us.”

Technology is moving rapidly before our eyes, and there are so many benefits that this advancement brings, but are there also negatives?

“With any new technology, you have to look at the positives and negatives,” Dr. Gandhi continues as I ask him on the less talked-about side of robot-assisted surgery. “I think the biggest thing is the financial aspect from the public health point of view – that’s huge. It costs a significant amount of money to buy a machine, but it also costs a huge amount to maintain.”

Looking at the cost of one of these machines, Dr. Gandhi goes on to estimate NZD $2 million outright with an added $200,000 for maintenance per year. That’s not even factoring in the tools used. Thinking about the number of surgeries performed around the globe, it’s no surprise that this industry is going well into the billions. Would the advancements in technology ultimately make it cheaper for us all? Only the big companies can say, really.

“It seems ridiculous,” the doctor continues. “Yes, the robotics may mean that there’s less conversion to open-surgeries compared to laparoscopic, but that also means those patients will get the benefits of minimally invasive surgery. They’ll recover faster and get you back to work faster, but that is looking at the whole picture. Looking at that, it would be more expensive doing it robotically.”

Another key risk of robot-assisted surgeries is, unfortunately, one that can’t easily – but must – be avoided. That of danger. “Surgeons had instances where the robot has locked into place,” Gandhi tells me. “They’ve had deaths related to the robot. If you get trained properly, I think that’ll be less common.”

Numerous reports were put online last year of the great training failures of student surgeons overseas, and even students in New Zealand who take to practicing in their own time.

“I think there’s complications with all surgery,” Dr. Gandhi reassures. “There have been studies that have shown that things have not been so well done invasively. We do have to keep an eye on those things. The robot numbers are very small. On the safety point-of-view, the robots are quite new and surgeons are still learning. I’d be cautious of getting rid of robotics based on what we know so far. From my perspective, I think the financial thing is the most important thing. Intuitive, they’ve done well from a money-making point of view, but people look at them oddly when competition ramps up.”

At the end of our discussion, I ask Dr. Gandhi what the future looks like for this type of technology.

“I think it is the future,” he answers. “I really do think that it’s going to take a long time before it becomes mainstream in New Zealand. In some parts of the world, it is. There are big centres in the States – they all have robots – same with South Korea and Japan. It’s infiltrated in Australia, as well. But with New Zealand, it will take time. We’ll have to wait for the price to drop and it’s better for the surgeon and better for the patient potentially. It’ll help us progress with augmented reality, and it’ll be better for patients. We can assess better structures and tumours. Potentially there’ll be automation in the body with different organs. Instead of it being robot-assisted, it’ll be robot-led. The surgeons are there to make sure we’re doing the right thing.”

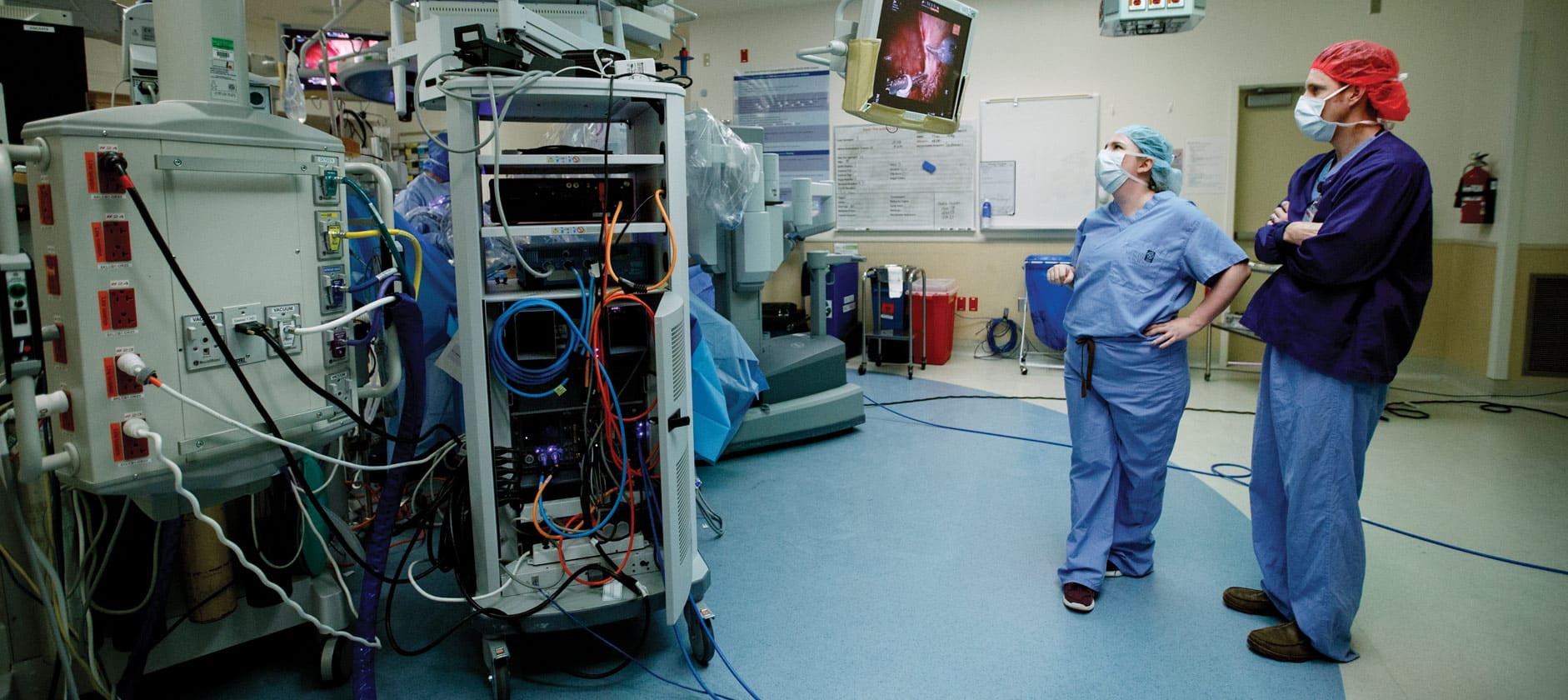

Top Image: Casey Seideman, M.D. watches the monitor to observe a resident’s progress during a robotic-assisted surgery, April 7, 2017. (OHSU/Kristyna Wentz-Graff)