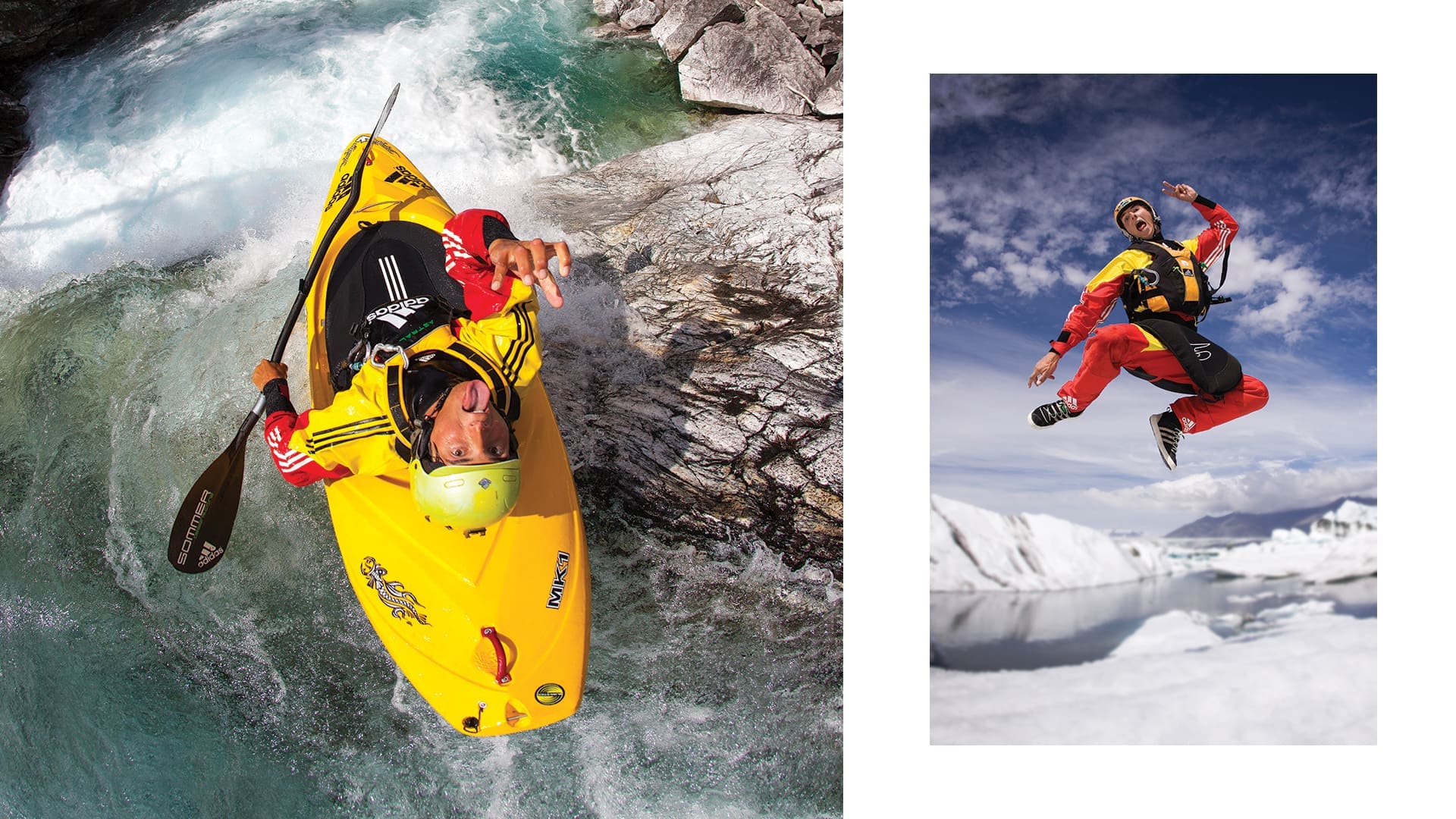

Going Past The Point Of No Return With Sam Sutton

Four times Extreme Kayaking World Champion and Rotorua local, Sam Sutton, describes the lessons that have come from going past the point of no return in kayaking, the relevance for life in general and seizing opportunities with full commitment. True to this, Sam seems to be living multiple lives. While not much past 30, he has travelled the world and achieved world acclaim for his sport, he has developed multiple businesses, including co-founding one of the world’s most respected kayak brands. Back home, he built Rotorua Rafting into one of the top tourism experiences in the world – achieving #1 Travellers choice experience in New Zealand, #1 in the South Pacific, and in the Top 10 in the world on Trip Advisor 2019 and then again in 2021, taking the #2 experience in the world spot.

Aside from this, he has also started Okere Falls Zipline, is developing a new mobile gaming world series, and is looking at providing further long term sustainable economic opportunities for his community.

I was trying to get my head around your bio – you are a four-time extreme whitewater kayaking world champ and a serial entrepreneur?

Sometimes I would think of myself more as a wanna-be entrepreneur, but that’s probably the next path that I’ve chosen to go down, after kayaking. Before, my whole life was consumed by this passion for whitewater kayaking.

I grew up in Okere Falls (just outside of Rotorua), so it has the Kaituna River flowing right through it, and it was just a natural progression really to get into the sport, even though I was reasonably late; I was about 14 when I started kayaking. Then over the course of the next 15 years, it was pretty much everything. Every waking moment was spent kayaking. Especially in my younger years, even when I wasn’t kayaking, I was just watching kayaking movies.

A part of me always wanted to travel the world, so kayaking was really that medium that allowed me to go and explore these places. And then that world just opened up more and more and more, the more I started kayaking. I ended up getting taken on trips to places I’d never even heard of before.

That was probably some of the highlights. It was just that travel experience and going to these places that are just so far from any destination that you would normally travel to.

Can you talk about any of those moments that really stand out to you as shaping your life?

It’s funny. I think in life the hard times are actually what you think about more so than any other time. One of the more memorable highlights was going to Altai Mountains in Siberia where Mongolia, Kazakhstan and China all come together. We did some pretty cool rivers there; a lot of big, wild expeditions.

You’re just so far from anywhere and anybody for most of the time that you have a real sense of freedom. I remember finding these ginormous log jams in these rivers and you’re like, ‘Man, you could light this on fire, it would be the size of a basketball court and nobody’s going to know anything about it’. So there’s an element of freedom that came with that.

When we were right on the Mongolian border, it’s the only area in Russia where you’re not allowed to sell alcohol, I believe. We had to do a covert mission to hop in the river at night time and paddle away from this village. There was a group that had paddled the river before us who had hopped on in the daytime and this village came down and ended up basically stealing everything from them and tying them up and pushing them naked into the river. I think there was a group of eight and only two survived.

There’s some cool experiences like that that you definitely don’t want to do as you’re older. But when you’re 24 and you don’t think about any real consequences, it’s easier to do.

One of the best trips I ever did was to Kyrgyzstan. We went in this off-road truck over a 5,000-metre mountain pass and then we paddled this river called the Sarydzhaz for eight days, right to the Chinese border. It’s an unmanned border. You hike along the border and the Tian Shun desert is just on the other side of this mountain range. So you’ve got this really weird haze, dust blowing in, and quite a surreal vibe going on in this area. You look up at the sky and you don’t even see a plane flying through there, you just feel so alone and isolated.

At the end of that trip, we had a three-hour helicopter ride out in this big Russian military helicopter that can fit like 16 people in there. It turns up and the weather starts packing up. And the captain’s like, ‘Go, hurry up, jump in, jump in’. We all load our stuff and he’s like, ‘Come stand right up at the front’.

There are three pilots to fly this chopper, it’s ginormous. They try to start and it doesn’t start. They got this toolbox, they’ve got a butter knife and they undid the flat head screws, changed the fuse and did it back up. And they’re like, ‘Okay, go, go, go’. I could just see the headline being like ‘Adidas kayaking team dies in a tragic helicopter accident’. We’re flying out and the weather’s just packing in, it’s started to snow. I believe the helicopter can only go to 5,000 metres in elevation and to get out, the lowest peak in the mountain was 5,000 thousand metres. It wasn’t until we had to stop and get fuel and we got some beers, that we relaxed really, but that was pretty epic. The captain also said, ‘The last time we flew in here, we crashed. But the good news is everybody lived, just the helicopter was screwed’.

Another story that I reflect on was we were paddling a beautiful river in Southern Mexico and there’s a guerilla group that lived there. And I definitely believe in what they’re fighting for, they’re actually fighting to stop deforestation because when you fly over that area, there are just fires burning everywhere. They live in the jungle to protect the forest, but they’re really anti-gringos.

We turned up and we were scouting this rapid, it was like 40 degrees and all of a sudden these dudes with these balaclavas and giant machetes come out and start questioning us. I couldn’t speak any Spanish, but my mate, he was French and he could speak some Spanish. We had a bunch of Red Bulls and a bottle of rum that we’d snuck in the back of our boats because it was like a three-hour paddle out in the flat water. So we managed to trade our way out of it because just a few months prior to that, they actually killed a couple of Americans.

When you’re surrounded by life-threatening situations, is there a part of you that is very conscious of your own mortality?

When I was younger, I was definitely conscious of my mortality, but for a period of time, you accept the risk and you’re just so consumed in the sport that it’s a hundred percent worth it. I’m living the dream here.

It wasn’t until a really close friend of mine died, and I helped out with the recovery, that really was the moment where that came real for me. From then on, I was just not willing to push it very hard. And as soon as you’re not willing to push and you’re not paddling confidently, then it’s time to walk away in my opinion because that’s when you make mistakes.

When you’re just full steam, you don’t make mistakes and you don’t have any problems to worry about really. It’s just when you take any second guesses and you’re not feeling confident, that’s when things happen.

That’s such an interesting insight because I can imagine there were times where you have got to be totally committed, you cannot falter.

A prime example in a river when you get into this 100% commitment, roll-the-dice style is when you roll into these gorges and they get cliffed out. It’s like a one-way ticket. Part of the beauty of that though, and I wish that was the case in so many parts of life, is you can go past the point of return and then you have nothing to worry about. You’re really worried until you go past the point where you can actually return and then there’s nothing to worry about because you’re stuck in here anyway, so now you just have to carry on. That’s such an awesome way to live life. It’s addictive.

I see it in a lot of my friends that we kayaked with at that time, that are now coming out of that stage. That’s probably the hardest part, actually leaving that area of your life and moving on because you’ve kind of become addicted to this and now you’re trying to wean yourself off it. You’ve lost a part of yourself because you’re not doing it anymore. So that’s where I’d say I battle with it most.

Is it tempting to look at other things to try and create those highs?

There’s definitely a void because you’re not taking these big risks. I probably have started taking bigger risks with investing or taking punts into random businesses and using that as my vice, but that’s definitely not healthy. That’s not a good bet. When you’re good at something, it’s far better to do that than when you’re not so educated on a certain subject and are just trying to send it.

I love that kind of metaphor that there’s a point of no return. Have you been able to replicate that in other parts of life?

Nowadays in business, I’ve gone down some pretty big rabbit holes with a couple of different projects that I’ve got going on. The main one that comes to mind at the moment is we’re building a zip-line project here in Rotorua. I thought it would take a year or so to get permission; it ended up taking two years and now another year just in development. And then COVID hit halfway through, but we were so far down the rabbit hole at that stage that you have to carry on.

But because you’re just risking material items as such, it’s just not quite the same as when you have your life on the line, I would say. The reward isn’t quite there.

Because you’ve been in those experiences where you are putting your life on the line, when you come to business decisions or just general life decisions, does it give you this sense of, what’s the worst that could happen?

One of the main things I’ve taken away from kayaking is how you break problems down. That’s what a rapid is, you’ve got this really big problem and there’s multiple sections of it. When you’re scouting a rapid that has the potential to kill you, you’re like, Plan A is to go here, here, here, here. And I just need to nail that point and then I can nail this point. And plan B is, where can I set up safety, somebody to catch me if I fall.

I take that approach into a lot of different things that I do. I try to break it down into multiple different layers and if I can continue to make every step, then I’m going to come out the other side. It’s just sometimes those steps tend to take a lot longer than the seconds that it took when you’re paddling the river.

Can you talk a little bit about the entrepreneurial things you have going on? Can you talk about how you balance everything?

At the moment, I’m trying to do a few different things and just trying to really test the water. Tourism was my main business at the moment. I have a rafting company in Rotorua that was voted the number one visitor experience in the South Pacific and number two in the world on TripAdvisor Traveller’s Choice. So growing that, we’ve added a zip-line, which I’m really excited about because it’s actually a joint venture with mana whenua. That’s been awesome just to develop this new product and we’re aligning it with a climate-positive experience.

Within that, there are so many projects. I started Waka Kayaks, which is actually probably the biggest whitewater kayaking manufacturing company in the world at the moment. I sold that a couple of years ago to my business partner, but that’s pretty epic to just see the growth that’s had. There’s a really cool film on Netflix called The River Runner, and Waka Kayaks is all over that.

Something that we’re just about to launch is we’re trying to build a mobile gaming world series, which is basically a new endless runner game every week. When that goes live, people have a seven-day period to compete for the highest score. You pay $2 to enter into the tournament and at the end of your week, the top 10 scores divide the prize pool; we’re starting with five grand. There are 2.2 billion people playing mobile games, so you can argue that it’s the world’s largest hobby and this goal is to try to turn that into a profession. Gaming is already a profession, but just to elevate the mobile gaming side of it.

Where did that idea come from?

I was sitting in a subway in Hong Kong and noticed everybody was playing games on their phone. I looked into some data and saw that it was a massive industry. I’m competing in a niche sport, so theoretically, it’s far easier to be good at what you’re doing, but I wondered who was actually the best mobile gamer on the planet, considering there’s 2.2 billion of them? It’s hyper competitive.

It was put on the back burner because I didn’t have the technical expertise, but I’ve linked up with a couple of people in Rotorua and we’re just ready to launch our first version out to the public, just to see how it goes and what we have to change as we go. I’m trying to start in New Zealand, so the goal is to try to find New Zealand’s best mobile gamer.

I like this idea that you can go from a 14-year-old, getting into kayaking for the first time in Okere Falls there, which leads you to these incredible, frightening and unique experiences all around the world. And then now you’ve gone in a completely new direction to develop an app that could tap into one of the most ubiquitous pastimes.

It’s definitely a random tension that we’re going down with that game. But I’m really excited about it because I don’t have a good technical background, in terms of development. When I’m talking to our coders and development team, I have to sit there and Google everything that they’re talking about at the same time.

But I just enjoy the process of developing something. I’m definitely a starter more than a finisher, so that’s the area that I’m really excited about at the moment. It’s just starting these different projects and having a bunch going on. I’m getting my adrenaline fix because I’m always under the pump.

Do you find that you need to have a structure to your day in order to be able to do all of the things that you’re doing?

I definitely need more structure. It makes a huge difference when you break down your day into time segments. To go to bed slightly earlier, wake up really early and hook into work just makes so much difference of what you’re able to take on.

By setting those structures up, layering everything that you have to do, and making sure you tick off the thing that is going to have the most significance in your day, just get that job done and then everything else can fall in after that.

You see these people and social media puts such a big question mark in your own self-confidence because you see, ‘How is this person able to do all of this stuff?’ Like it’s impossible. I’m sure there’s a lot of smoke and mirrors. I have so many days where I feel I’m productive. I feel good at the moment because we have quite a large team of people that are all doing things.

What advice from your life and experience could you pass on to other people who are just wanting to live their life to the fullest?

When you’re faced with fear, when you come to a really hard rapid or your pedal snaps, you have an equipment failure, you’ve miss your line, the water takes you, you’ve misread the rapid and there is no doubt in your mind that it is going to kill you, you have to make the decision whether you’re willing to take the risk at that time.

I think you’re better to take the opportunity, than to regret missing the opportunity.

Top image by Jens Klatt.