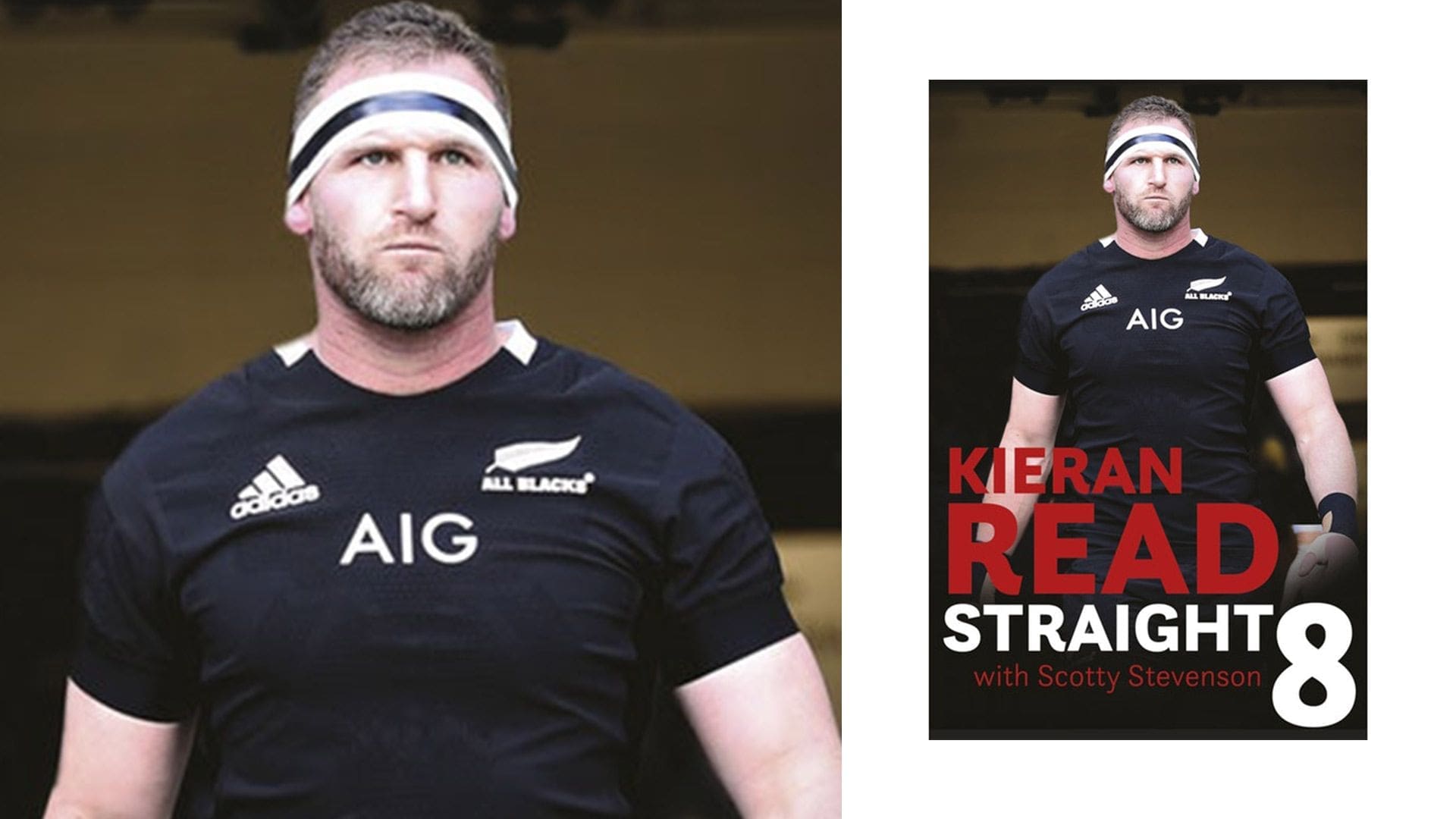

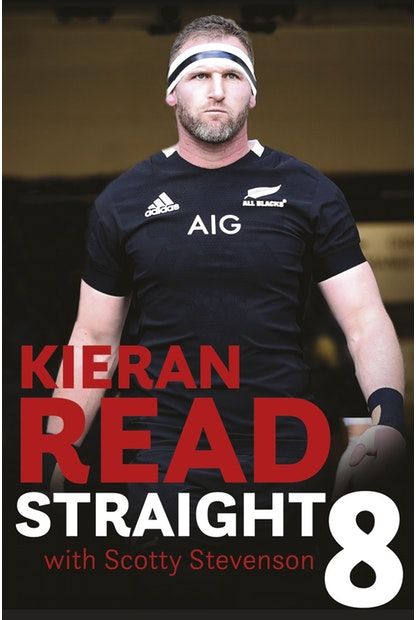

Kieran Read: In The End

Since he first put on an All Black jersey as a 23-year old in 2008, Kieran Read has amassed more than a century of test appearances. Now, after a stellar provincial, club, and international career – including back to back World Cup victories – the New Zealand captain writes openly and honestly about his time in the game. Read lifts the lid on the unique pressures of succeeding as captaining the most celebrated All Black team of all time.

He outlines the decisions that shaped his career and uncovers the skills of the coaches who shaped him, while offering readers an inside account of how the world’s greatest team functions and thrives. A rugby player cannot reach the pinnacle of the sport without negotiating the many avenues of adversity on the road map to triumph. Read unpacks the emotional toll of injury and the ignominy of defeat, neatly illustrating the intense experience of representing a rugby-obsessed nation while delivering a masterclass in how manage the many demands on the mind and on the body. Read shares a chapter from his book Straight 8 with us here.

The tears stopped on Monday, but the hurt refused to leave. I doubt there is a hole deep enough to bury it. There will be days to come this week, and next, and then the month after that, and maybe in a couple of years, when I will trip over some jagged, rusting edge of it and open a fresh wound that refuses to fully heal. That’s the way defeat works, especially when all I had thought about for four years was victory.

The tears stopped on Monday and frustration filled the void. We sat slumped in the All Blacks team room, in a forest of Tokyo high rises, where two days after the semi-final of the 2019 Rugby World Cup we reviewed the game. Okay, let’s be honest here: we reviewed the loss. In every frame, a missed opportunity; in every clip an alternate reality: a technicolour tragedy rendered in slow motion serving first to magnify regret and then to strengthen resolve. We watched in disbelief to begin with, a room of shaking heads and downcast faces.

And then we snapped out of it.

‘Are you happy, Daddy?’ That was all my little boy Reuben had wanted to know the day before, which was the day after my 34th birthday, my toughest night as All Blacks captain. He had looked up at me, his tight curls of hair as blond as pine shavings tumbled around his cheeky face, and I had smiled then and thought I was. Right in that moment, I was. Pain comes in waves, though, and Monday had been tough again. The review had made it tougher still — the honesty, the clarity, the sheer ease with which we could see things then that on Saturday had been so uncharacteristically hidden from view. We had to draw a line under it, then and there. We were lucky to have one more chance that week to show what we could do. We had one more chance to play for our country.

My body was wrecked after the England test. I had run further in the game than in all but a handful of test matches before. The usual aches and pains taunted me, taking turns with all-new areas of interest and inflammation to protest against a full range of movement. Movement, however, was what was required. We needed to move forward, to accept that what might have been will never compete with what was. On Monday night we drew a line in the sand. Yes, a semi-final loss was a long way from what we had wanted, but there was no do-over. We had been beaten, fairly and squarely, and now we had one more game left. It would be my last.

The laughs started on Tuesday. I had invited the boys of New Zealand operatic trio SOL3 MIO to the hotel and they spent the evening singing for us and bringing the house down with their jokes. It was a classic night, one that was very much needed by all of us. In those few hours together, I think we began to remember what was important: being around the people you cared about and appreciating everything that went with being a part of this famous team. On Wednesday that notion was reinforced when all the families came for dinner with us. The same people who four days earlier had been there to console us were back to their encouraging best. Across those two evenings, we rediscovered our emotional centre. We knew then that we had to enjoy the few days we had left. By the final Thursday training run, we were thinking only of what was in front of us: we had a test match to play, against Wales.

There was something else, too. The messages of support we received during the week were overwhelming. I had been so disappointed for everyone after the semi-final, for the team and for myself, yes, but also for the many thousands of fans who wanted us to deliver them another title. I had carried that weight with me over those first few days, but with each new email, or text, or phone call, the burden was eased. There had also been an incredible gift: the Minister for Sport and Recreation, the Hon. Grant Robertson, presented Steve Hansen and me with taiaha on behalf of the government as we prepared to say goodbye to the team we both loved. It was a humbling gesture, and a taonga that will hold pride of place in my home.

On Friday, 1 November, I gave my final pre-match talk. The guys will tell you I almost lost it, and they’re probably right. It was hard not to be emotional in that moment, but the tears had been used up. ‘Do it for yourself, do it for your mates, and do it for the people closest to you — those you really care about.’ I think in all honesty I was talking to myself more than anyone. A few moments later, I led the team out onto Tokyo Stadium, smiling, just as I had at the coin toss alongside Alun Wyn Jones, the great Welsh captain. He had smiled back. ‘Well, mate, what the hell are we doing here?’ I asked him, ruefully and rhetorically. It was his 143rd test match that night, making him the northern hemisphere’s most capped international. A man of great integrity and immense talent, Alun Wyn had been a sensational rival over many years. To stand there next to a captain of his class was an honour, and that moment brought fresh perspective. Yes, we were playing a day earlier than both of us had hoped, but how lucky we were to lead our teams in a test match. ‘You said it, not me,’ came his cheeky response.

When the team was named early in the week and TJ Perenara had been given a rest, I knew I would be leading the haka. Only once before had that honour fallen to me and I felt an enormous sense of pride that I would get to act as kaea in my last appearance in black. We chose ‘Ka Mate’, only because it was still us. It felt right for the night for how we wanted to represent ourselves and the jersey and all who had come before. I had come to truly appreciate the significance of the haka, especially in the last few years. It was more than tradition for me — it had become a portal to a new world of learning, and that had made me a better person.

The Welsh lined up on halfway and accepted the challenge. We knew what we wanted to do and what we needed to do, and we also knew that they were as motivated as us. Yes, we were saying goodbye to our coach, but so were they. We knew they would give it everything they had. Unfortunately for them, their all would not be enough. Over the next 80 minutes, everything that didn’t work the week before suddenly clicked into place. The sight of Joe Moody sprinting 30 metres to score the first try was one to savour. Beauden Barrett did Beauden Barrett things to score the second. Ben Smith — surely one of the classiest players in history — chimed in with a double that only he could have manufactured. My mate Ryan Crotty got served up a Sonny Bill special. Richie Mo’unga finished the job.

The smile stayed on my face for the entire game and when Wayne Barnes blew the final whistle, I felt an enormous rush of pride. Six days earlier I hadn’t been able to look my teammates in the eye, but now I took everything in. It all felt hyper-real, the green of the grass, the glare of the lights, the noise from the crowd, the satisfaction on the faces of my mates who had done this with me one last time. One last time.

Through the chaos I found Bridget and the kids and one by one they joined me on the field where they ran around laughing and having the time of their lives. Everywhere I looked there were children giggling and playing, some dressed in black and others dressed in red. We stood there waiting for the presentation, chatting away with each other and with the men we had defeated. It felt like we were all back on the club field having played for the love of it alone. Maybe that was what we had just done that night. Played for the love of the game, and for each other. Could I think of a better way to finish? Sure, a little gold cup would have been a nice addition, but in those minutes after the match, my cup was full.

One last press conference. One last shower. One last beer in the sheds with the men I admire. What a pleasure it had been to captain them. We left the stadium and boarded the bus for the drive back to the team hotel, each of us feeling the satisfaction of victory. For some of us — Ryan Crotty, Ben Smith, Sonny Bill Williams, Matt Todd and me — it would be our last. We knew that before the game. We had each been given the chance to go out on our terms. I looked around the bus, a beer in hand, smiling still, and hoped that others would have the opportunity to be a part of this team for as long as I had been.

I felt time slipping away. I think a part of me wanted to hold on to these final hours forever, even though I had made my peace with letting go. I sat in the vast lobby of the Conrad Hotel and gathered my thoughts. Upstairs, hundreds of family and friends had gathered to celebrate the end of the tournament and the end of this All Blacks team’s time together. We would always be bonded by the brotherhood forged in the furnace of international rugby, but this team’s era would soon be over. That was always the way it was with the All Blacks: the desire to succeed remained the only thing that never changed. The cast was a revolving one. My time on stage had come to an end, all the lines written and performed.

I took a long sip on a can of cold Japanese beer. The body was beginning to ache again, but that would pass. It always did. Enjoy this, I told myself. Get yourself up those stairs and hold your wife, and hang out with your mum and dad, and your brother. Treasure the drinks and the laughs with them, and with all the other families. They are yours, too. They are the people who make us what we are, and who support us through it all. They’re the ones who feel the pain like we do and feel the same pride. And, hell, be proud. You’ve done all right, mate. You gave it your best, and that has to be all you can ask. You had a dream and you chased it, and you chased it with everything you could muster.

It had all been amazing, really. I had been given the chance to represent my country in 127 test matches. I had won my first, and I had won my last, and I’d won 105 in between. I had gone the distance in 106 of those tests and led the side in 52. That was the simple accounting of it all, but numbers alone don’t do justice to the story…

It had all been amazing, really. I had been given the chance to represent my country in 127 test matches. I had won my first, and I had won my last, and I’d won 105 in between. I had gone the distance in 106 of those tests and led the side in 52. That was the simple accounting of it all, but numbers alone don’t do justice to the story…

Extracted with permission from Kieran Read: Straight 8, written with Scotty Stevenson ($49.99 RRP, Mower, an imprint of Upstart Press). Available where good books are sold or from upstartpress.co.nz