Making An Impact On Sir Bob Geldof

When life gives you lemons, you make lemonade.

In this context—and stretching out that hackneyed proverb far—when life gives you a bright, bold Hawaiian shirt, you wear it to hopefully serve a sprinkle of personality, a razzmatazz or showmanship, in situations you know for a fact will never occur again in your lifetime.

When given an opportunity to chat with Sir Bob Geldof for 30 minutes on his tour An Evening with Bob Geldof, set to hit New Zealand in March, I chose the brightest one I had.

‘Thank you for agreeing to this interview!’ I exclaimed (or semi-barked) at Geldof, red-faced, flustered and noticeably sweaty, ‘I’m very excited!’ Understatement of the goddamn century.

‘No problem, mate,’ he replied in his trademark Irish lilt. Bob is certainly a captivating man—charismatic, likable, charming and almost luminescent under this rockstar-living-legend energy he seamlessly emits. ‘Thank you for wearing such a weird, colourful shirt for me to look at!’

With my brain spinning rapidly from his compliment, I decided to then bellyflop face-first into a drawn-out anecdote of how I acquired the loose-fitting Aloha. I flailed around my words, like a floppy tropical fish out of water, almost ripping the shirt off my body so he could catch a closer glimpse at the pattern. My attempt at ‘making an impact’ was very quickly turning—so early in our interview—into me just ‘making an absolute pillock of myself’.

I started telling Bob about my mum (and now step-dad)’s wedding in Las Vegas at the world-famous Little White Wedding Chapel—located smack-bang between Downtown’s bustling Fremont Street and the Paradise boulevard—in 2023, like I was reminiscing casually to a close family friend.

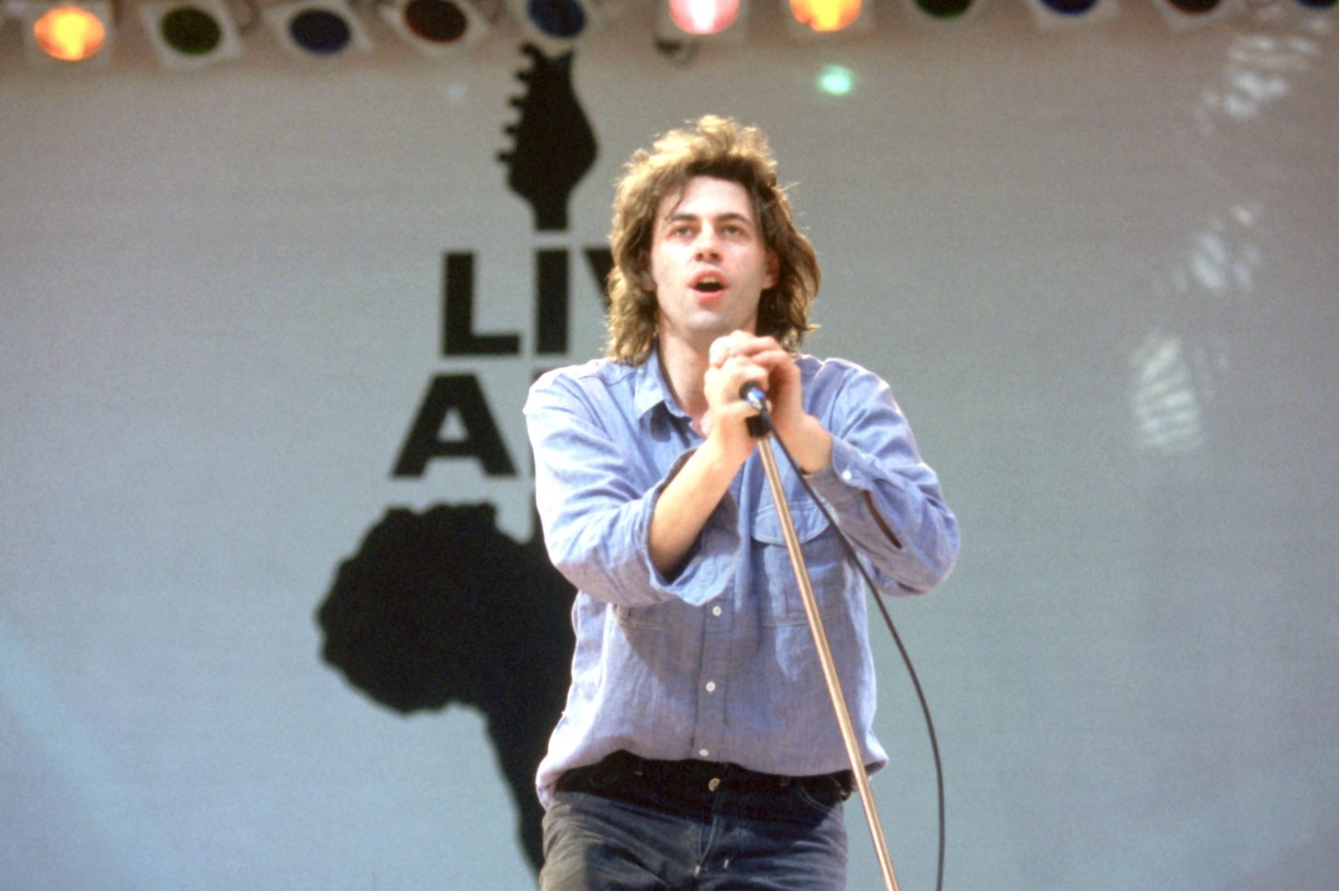

I suppose he is, in a way. He’s a family friend to everyone. He’s certainly part of everyone’s collective lives, what with organizing and orchestrating the biggest celebrations of musical unity the world has ever seen—Live Aid in 1985 and Live 8 in 2005—which, collectively, raised astronomical amounts of charitable aid for Ethiopia and Africa.

Bob’s name has been emblazoned into the global cultural fabric since forming the chart-topping New Wave band, the Boomtown Rats, in 1975, who are still going strong after seven studio albums. ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’, ‘Rat Trap’, and ‘Diamond Smiles’ are still heralded as some of the greatest rock anthems. And who could forget one of the fastest-selling (and best-selling) singles of all time, ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’, that Geldof co-wrote with Midge Ure in 1984. Midge (real name James) was also a driving-force in organizing the superconcert, Live Aid, a year later and stood proudly alongside Geldof in the Band Aid charity supergroup, a band that featured the biggest musical names of the 80’s.

Band Aid was formed by Geldof and Ure to raise money for aid efforts in Ethiopia that, at the time, was suffering from the worst famine ever recorded in the 20th century, as well as being under the siege of a Civil War under a Communist government. It was Michael Beurk’s BBC News report on the burgeoning crisis that inspired the creation of the Christmas song.

The donations that were made from the hit charity tune saved over a reported two million lives. ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ ultimately then influenced ‘We Are The World’ by American supergroup USA For Africa, written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie.

And we all know about the 1985 Live Aid, don’t we? Billed as The Global Jukebox, that colossal 16-hour superconcert—staged simultaneously in the UK and USA—featured over 75 musical acts, such as Queen, Madonna, U2, The Who, Sir Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan and Sir Elton John, to name but a few. Beamed to 150 countries around the world via 13 satellites, Live Aid was and is still one of the largest satellite link-ups and television broadcasts in history. And Geldof was the driving-force behind all of it. Band Aid and Live Aid combined raised over 150 million dollars in donations and, reportedly, up to 40 percent of the world’s population tuned in to watch it live.

Over the years, Bob’s advocacy and fight for justice and change is nothing but awe-inspiring. The founder and chair of several charities, an honorary Knight of the British Empire, a Class II Grand Officer of the Sudanese decoration The Two Niles, a World Summit Man of Peace Laureate and the recipient of the Freedom of the City of London. With his ardently outspoken nature—a passionate provocateur, some would say—Geldof has successfully convinced several Western governments to change their foreign policies to prioritise humanitarian concerns. He has advocated to plutocrats, popes, presidents and prime ministers and has more Nobel Peace Prize nominations than any other living nominee. What a CV.

With such a dazzling résumé, one can only imagine what was on the forefront of Bob’s mind as I—this clammy, tightly-wound-up, odd-looking, trembling twit from Aotearoa, New Zealand—continued my damn hardest to try and ‘make an impact’……with a f**king shirt.

‘Woah, woah, woah,’ Sir Bob interrupted me mid-sentence, abruptly.

I froze. My stomach flipped. My heart lodged itself in my throat. Had I gone too far? Didn’t he want a closer look at my tacky Hawaiian Aloha?

‘Back-track, back-track!’ A pause so thick I could’ve cut it with a knife. Was I about to get scolded by the living musical legend? Then: ‘Your mum got married?…In Vegas?’ Geldof grinned, a twinkle in his eye.

Hook. Line. Sinker.

It hadn’t dawned on me then that he may have made some connection to his own highly-publicized Vegas wedding in ‘86 to ex-wife and dearly departed British national treasure Paula Yates. They tied-the-knot at the Little Church of the West in the now-demolished Mexican-themed Hacienda that had stood at the southern end of the strip, where the luxury Mandalay Bay and pyramid-shaped Luxor are now. Their nuptials were attended by the likes of Simon Le Bon from Duran Duran (who was also Bob’s Best Man in the ceremony), David Bowie, George Michael, all of Spandau Ballet and all of Ultravox. As you do.

So to break-the-ice a little bit further before our interview, me and my new mate Bob yarned casually about my mum’s wedding. How my older brother and I—both very, very sleep-deprived after all the clubbing in Caesars Palace’s Omnia and what the various delights of Sin City had offered us—then spent a couple of respite-days in Waikiki, Hawaii. I told Sir Bob that I just had to buy a shirt—as a memento, a souvenir. ‘Wouldn’t you?’ I questioned Geldof.

He nodded and laughed. ‘Sounds like all you did in Hawaii was turn up and buy a whole new f**king wardrobe of shirts!’

If anything, my shirt was my lemonade-maker (or ice-breaker) in this case. When life gives you a crazy Hawaiian shirt, wear it to make an impact during crazy opportunities, even if the impact of wearing such a bold thing fails pretty miserably in comparison to the greatness of the person you’re actually speaking to. Because—without any exaggeration—Sir Bob Geldof’s impact on the fabric of the world has been revolutionary, dramatically altering the landscape of international aid, trade and policy for decades, and his accomplishments have paved the original stepping-stones for celebrity-led activism. This man is the living definition of a musical legend.

Set to tour both Australia and New Zealand in March, An Evening with Bob Geldof is going to be unforgettable, to say the least. It’ll be a celebration too. 2025 marks the 40th year anniversary of Live Aid and 50 remarkable years of the Boomtown Rats. From his teen years in Dublin, Ireland, to his world-renown music career with the Boomtown Rats, to Band Aid and Live Aid, Geldof will share his captivating journey through his incredible life.

Is New Zealand ready for An Evening with Bob Geldof next year? I think we’ll be too excited! Our little kiwi nerves won’t be able to handle it!

I think the real question is: Is Bob Geldof ready for New Zealand? And I think the answer is no! Because I haven’t a f**king clue what I’m going to be going-on about! By the time I get there, I’ll have the songs worked out—the ones I wanna do—and all the stories worked out. We still have to write visuals and fill-ins, but at the moment it’s just constantly noodling around my head. What should I put in? What should I leave out? What does the audience want to hear?

That’s nervous for me and I’m not usually nervous. When I’m with the Rats, it’s second-nature. I’ve done it for 50 years. The Band Aid and Live Aid thing I can talk about until I’m blue in the face. But actually standing on a stage alone, that’s not normal for me. I’m having to really work out what it is I’m going to do. Nerves are an unusual situation for me.

So no sneak peeks, or tasters, you can share with me?

I’m not sure, you see! Honestly, these interviews have all been good because the interviewers and DJ’s more-or-less ask the same things. They’ve been asking because this is what their audience will want to hear. So if that’s what their audience wants to hear (by definition) it’s what my audience will want to hear too.

Beyond the obvious Band Aid, Live Aid or Live 8 stories, there are heaps I’ll forget (or have already forgotten). People can remember—this happened, or that happened—but what people really care about is how it happened to me. I’ll be almost brought back to a pre-fame life and what that was. In truth, if audiences are listening to me, it’s more predictable than the rock n’ roll stuff and becoming ‘a hit’. That’s pretty linear, and audiences can see why one thing leads to another. Even that is very limited: working at a slaughter-house, riding heavy-machinery—yada yada yada.

Inevitably, I would talk about that on the more serious shows. I’m going to have to do a timeline and be linear.

I don’t suppose you (and I’m talking directly to you) have ever thought I am where I am now because I planned it out this way perfectly. We all have that sliding-door moment where we go down the road-less-traveled.

I’ve only got a couple of hours, and an intermission. So how do I willow my whole life down so it’s a great evening and people leave going: that was f**king great? I want them to feel like they’re leaving a Rat’s show going that was unbelievable! I want that same reaction. But how do I get there? With just talking about myself and playing the guitar? This is probably boring for you, and I keep on annoying the people around me, because I’m constantly like what the f**k do we do?

Sorry, I’m talking through my problems!

Do it! Tell me how you really feel! Let it all out, mate. So, An Evening With Bob Geldof will—

Oh, by the way, I’ve changed the name!

What, really? What have you changed it to?

It’s now called: Life…WTF?

You’re joking me. That is brilliant.

Yes, I am brilliant. I think you’ve realized that over these short minutes together. I think it suits it better. Sort’ve like what I said: no one knows what the f**k is going on. Two and a half weeks ago, I spent three days filming a zombie movie! I mean what the f**k!

I heard about that! How’d that come about?

I was in Brisbane for a conference and we turned up at the International Film Festival and met a friend. They were showing a zombie-kangaroo film—I know, don’t ask! She said that she was starting a new project and asked if I would be interested in doing a cameo. So I spent three days cameoing in a f**king zombie movie! Don’t ask me what it’s about—I haven’t a f**king clue who’s in it! I don’t think the director knew what it was about either. But, in life, if anyone asks if you fancy doing a zombie movie, the answer is: yes, of course you do!

Certainly a moment when you must’ve thought: sod it, why not, right?

It’s not something I’m proud of! I’m not going to narrate my many labors of being a zombie to the audiences of New Zealand, that’s for sure!

You have had such an amazing life with the Boomtown Rats, to Band Aid, Live Aid and Live 8, to your passionate global humanitarian efforts. You’ve inspired generations of thinkers about global issues. Your tour will inspire the New Zealand audience. How have you felt inspired through your career? Who inspires you?

The people who got me through life were all the people you probably know about. I came of age at exactly the right moment to absorb The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Bob Dylan. I was 11 when they arrived. Things weren’t great in my life. They allowed me and instructed me in the possibilities of what I could do. That I wasn’t constrained by my own circumstances and that change is desirable and inevitable. I learnt that the rhetoric of change is rock n’ roll, and therefore the platform for change is music itself.

From that point on I read books which somehow mirrored in a literate way a different world to what I thought I was experiencing. Woody Guthrie’s biography, James Baldwin, John Steinbeck’s books and Dickens. I wasn’t good at school, because I wasn’t cooperative with the authority. I began doing things like organizing anti-apartheid marches at 13. Sounds very grand—like I was a complete pain-in-the-arse (I probably was), but a low-grade pain-in-the-arse. I kept my head down.

Then at around 16, I didn’t go home anymore. I stayed out in Dublin working with homeless people. Rock n’ roll was the thing that guided me. Politically, socially, economically, philosophically, theologically. I was getting to those boys and girls (not much older than me). There’s not a big age difference between a kid and a 19 year-old, but a world of difference in maturity. It sounds really cliché, saying what inspired me, but that.

And I continued reading those books. I was reading them because my heroes, Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger, were telling me that they were the books they were reading. John Lennon was always crapping-on about the books, so I read them. Eventually, they filtered down into the music itself. Because if the music wasn’t there I would’ve dreaded those books. Would they have had the same inflammatory impact? No, no they wouldn’t. But that was the language. You could articulate that into the songs. The function of music is to often articulate the inexpressible. As a younger person, if life isn’t great around you, then music is the golden-thread of virtue. And I grabbed it and never let go.

Since your start in 1975, has the power of that ‘golden-thread of virtue’, the music, ever changed for you? Or has it always been this monumental, huge force in your life? A force for change?

It has changed, because I don’t think it was as powerful as it once was. Rock n’ roll was a 50-year-pop. If you take from, say, 1956 to 2006, you’ll see huge change. Elvis and Little Richard—of course you’ll see glimmerings of rock n’ roll before that—were the start of the explosive revolutionary energy that it was. It was a function of the economy, society and technology. You didn’t have Elvis and Little Richard if you didn’t have the transistor. You didn’t have Elvis and Little Richard if you didn’t have the Pax Americana and the glue that linked the Empire post-war.

The glue that linked the troops all over the world was the language of these young boys via rock n’ roll. It reminded them of home and spoke to the American dream, which they’d never been allowed into.

That was what Elvis was doing—this instinctive animal—who physically and sonically represented the frustration of not being allowed into the cornucopia. He represented the man, the man and woman, the blonde girl or the brunette muscular boy in the back-seat of the Ford Cadillac driving forever into this eternal America. He represented the ones who weren’t being ‘let in’ or were on the wrong side of the tracks. Elvis got on tellie (very young and beautiful and instinctive), and was a f**king animal. He had to be tamed. As John Lennon once said: ‘Elvis died when he went into the army’. Little Richard—young, beautiful, black and gay—there was no f**king way he was getting on television! So he just screamed this inarticulate scream of rage. ‘Wop bop a loo bop a lop bom bom!’ If you were in f**king Vladivostok or Dún Laoghaire, Dublin County, Ireland, you absolutely knew what he was on about. ‘F**k off!’ Richard screamed. ‘We’re coming!’

Then you don’t get The Beatles without television. We got these working class boys who didn’t understand why they have to be differential to authority; they didn’t get it, so laughed their way through. The middle-class boys, The Rolling Stones, were just sneering at the contentious insolence. Then Bob Dylan out of the midwest of America, just questioning and being all: what the f**k!

Music travels down. You don’t get the punks without Thatcher and Regan and a rejection of that. Or you don’t get Band Aid and Live Aid without satellites. With Live Aid we worked on faxes and telexes. The satellites linked the world. And then we didn’t get Live 8 without this beast called AOL. One year before Live 8, Google made a profit for the first time ever from making you the product. They sucked up your digital exhaust and sold it on. Capitalism changed. Instead of producing stuff, you were the product and consumer. Live 8 was the last hurrah of rock n’ roll, really. It changed because rock n’ roll was the cultural spine of our life. It was the spine of culture, and the cultural spine of our existence.

Even though the music nowadays is fantastic and brilliant with brilliant writers and artists, it’s slipping back to how it was in the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s. The music is there and exists in the background (where you have your favorite tracks and artists) but they don’t inform you. They don’t posit difference. These new artists articulate it, but don’t offer it to you. What we all have in our pockets, the means of instant gratification, that’s the cultural spine now. You can see its effects on America. It’s completely altered the world’s economy, therefore society. The confusion of that then leads to a weird politic and a break-down of systems, but it isn’t rock n’ roll positing the answer to that now…it’s the phone, or the computer. So rock n’ roll as a necessary force is no longer there; rock n’ roll is just seen as another great form of music. It has no more relevance than the soundtrack to your life.

But I’m not going to be talking about that in the show! It’ll bore the arse off everyone!

I’m just a bit stunned, and so impressed, by how insanely good that answer was!

The expression on your face read more: what the f**k is he on about?

I didn’t think that at all! What a treat! Thank you for that. Final question…It would be remiss of me to not ask you about Live Aid and the outstanding positive global effects it had. Do you still think back on it and are shocked that you were able to organize and accomplish such a mammoth thing?

I mean, if you asked me three weeks ago, it would’ve been ‘just there’. It was just a part of my life. Because of the Band Aid record anniversary, I asked producer Trevor Horn to take the three official records from ‘84, ‘04 and ‘14 and put the generations together. I wanted it on track and to make these young kids—these boys and girls—sing. He’s done it—literally just before speaking to you I watched the trailer for the new video—and it’s extraordinary, and moving. I never expected to be moved by it, you know. While [Live Aid] was a big part of a life (and I’m asked about it constantly) I didn’t necessarily feel the romance the first time around. I was on a mission to achieve X. Structuring how to get there was always in my head at that time. When we needed a song, for example, or a singer, it was moreso: f**k it, that’ll do. If we needed to record it, or get lighting guys, or sound guys, it just happened off-the-cuff…it was very full-on.

Retrospectively, I see the beauty of it that others got, but I missed. People say: ‘oh my god, Bob, thank you, it was the best day of my life’. Literally it happens all the time. We walked out of a studio in Melbourne recently and the head of the station came out and thanked me. In those moments I think that’s really nice. It’s unexpected, but not unusual.

It was only in putting the three generations together—to see a young Sting beside a young Ed Sheeran, or a young Bono beside a young Harry Styles, or a young Boy George beside a young Sam Smith—I thought: that’s the entire arch of British rock over 40 years. It’s deeply impressive. Here they all are, singing on this okay-ish tune I wrote.

The hasband was Sir Paul McCartney, Thom Yorke on piano, Midge Ure, Gary Kemp, Damon Albarn, Paul Weller, Roger Taylor, Jonny Greenwood, Phil Collins, Danny Cummings on drums. You’d think: that’s insane. The amount of talent was nuts!

So looking back on it, it’s moving for me, yes. But other than that…it’s just part of the fabric of being.

Sir Bob Geldof will bring his highly-anticipated show, An Evening with Bob Geldof: Songs & Stories From An Extraordinary Life…WTF?, to the Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre on the 28th of March, 2025. He will then take it to the Michael Fowler Centre in Wellington a day later. Head to tegdainty.com for all ticketing and tour information.