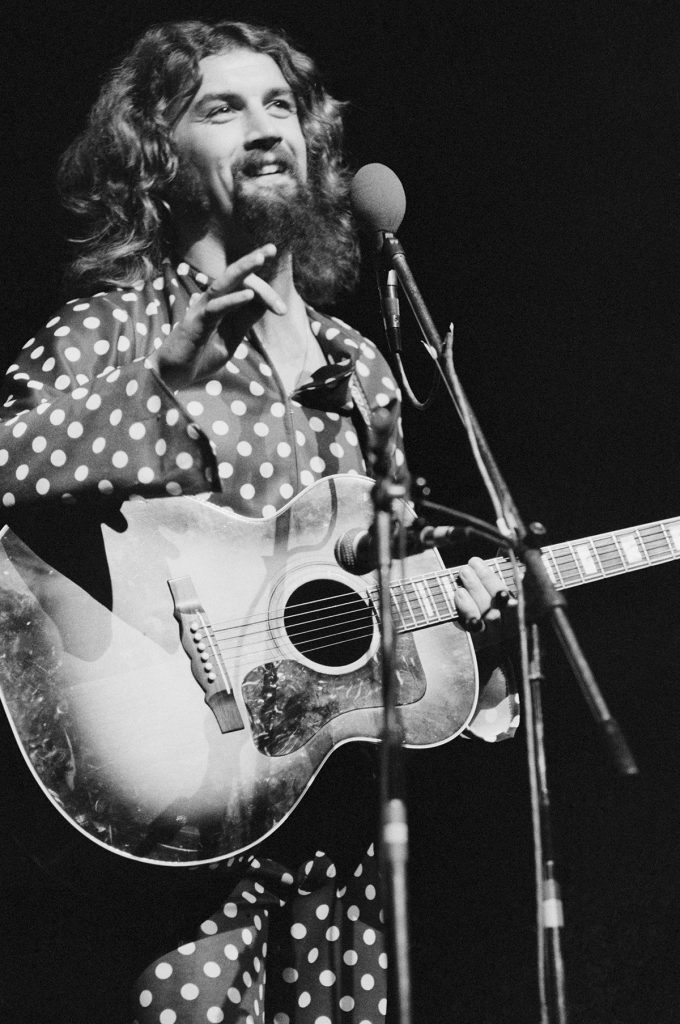

The Big Yin – Billy Connolly

It’s hard to think of comedy without Sir Billy Connolly. The man is funny, intelligent and (most importantly) respectful. His stand up comedy sketches are renowned for their wit, poignant social commentary… and of course: his foul language.

Born in 1942 in Glasgow, Scotland, Billy grew up in a tiny apartment with his teenage mother, and two siblings, Florence and Michael. His father had gone to fight in the war and their mother abandoned the family without explanation, leaving Billy and the others to learn to fend for themselves under the care of their two aunts. It was when he was eight years old that he realised that all he wanted to do was make people laugh. From there, Connolly’s story unravelled and in the early 1970’s, he quit his job as a welder to pursue comedy full-time. He’s definitely paved out a legacy for himself and (in the process) for other budding comedians. He’s won numerous awards, including a BAFTA, Screen Actors Guilds, Honorary Degrees and Doctorates from high-ranking universities. And his knighthood can’t be unnoted. His new biography, Made In Scotland, was launched last month and tells of his love for bonny Scotland, for comedy and the legacy he’s learnt from. Off the back of his BBC documentary, Coming Home, this book tells of what makes Connolly stand out above the rest. Below is an abstract from the book, courtesy of BBC Books.

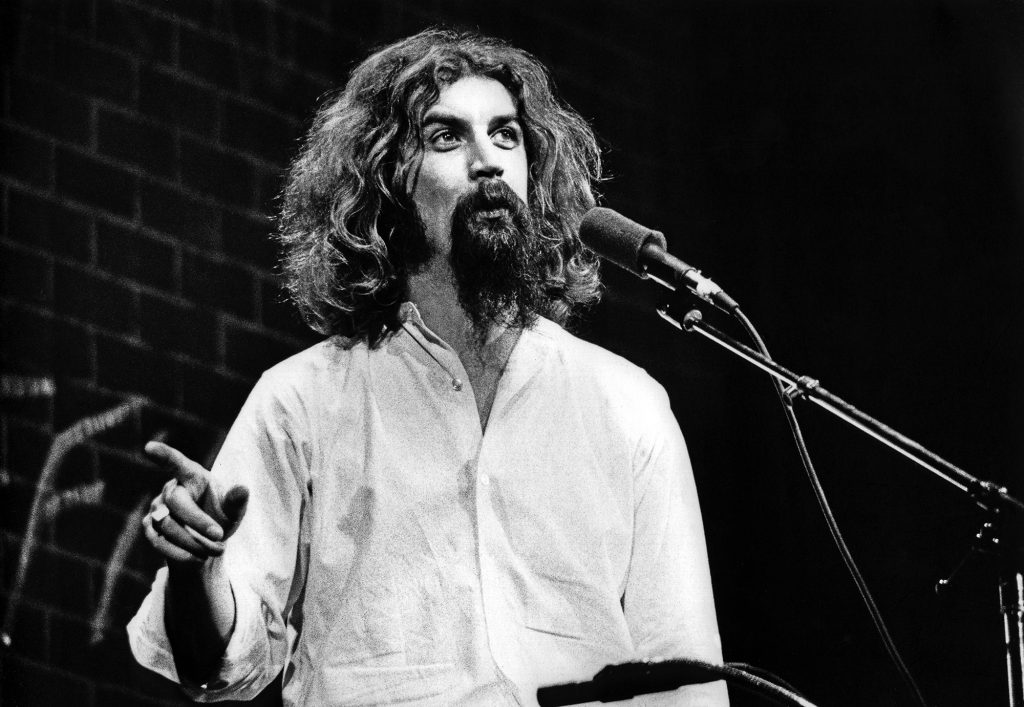

I had made my name in the Humblebums with my storytelling and my comedy routines between the songs, but after Gerry and I split, I still thought of myself as primarily a folk singer who told jokes. There was a guy at our record label, Nat Joseph, who had worked with Hamish Imlach, and who encouraged me to go more for the comedy side of things in the way that Hamish had but, in my mind, I was a musician. My storytelling stuff was still new and growing and I never went on stage with the first idea of what I was going to say. Often, somebody might just tell me a joke then I’d tell it to the crowd in an extended fashion.

This happened to me one night when I was drinking in the Scotia Bar and a pal called Tam Quinn, who played guitar in a band, wandered in and told me a wee joke. He said, ‘Jesus’s apostles were eating a Chinese takeaway when Jesus came in. Jesus asked them, “Where did you get that?” and they said, “Oh, Judas bought it. He seems to have come into some money.” ’

I thought it was the funniest thing I had ever heard and I told it onstage that night with some little added bits. It went down extremely well. I was very encouraged by this, so I started to tell it at every show and expand on it. As a way of introducing it, I said that there had been a terrible mistake and there was a misprint in the Bible – Jesus hadn’t really been born in Galilee but in Gallowgate, in the middle of Glasgow, and the Last Supper had taken place in the Sarrie Heid. I kept on expanding and developing it and adding dialogue. I called Jesus ‘The Big Yin’, which is Scottish for the Big One:

The Big Yin came in with his long dress and his casual sandals and his aura: ‘Ah, I’ve been all morning doing miracles, I’m knackered – gies a glass o’ that wine!’…

They all sat down at a long table, ’cause they were having trouble standing up. You might have seen the picture – the Big Yin is holding on to the table ’cause he’s steamin’ …

The Big Yin says, ‘See you, Judas, you’re getting on

ma tits!’ …

‘Ah, man!’ the Big Yin yells, when he wakes up. ‘Some joker has nailed me to the wood! Stole my good dress and pawned it and left me lying here in ma Y‑fronts

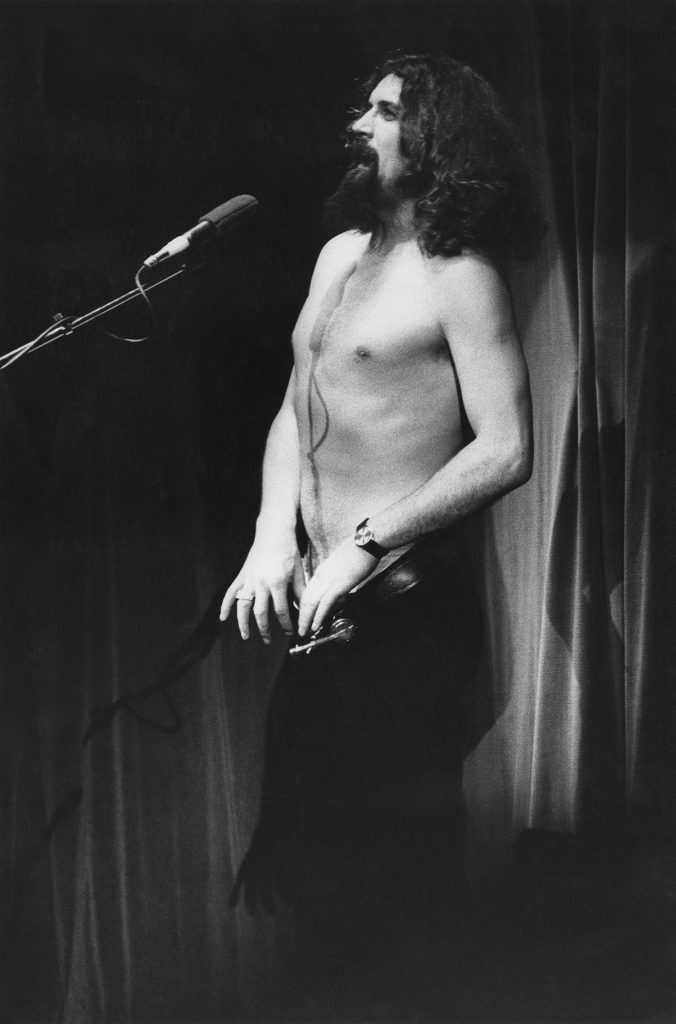

I kept adding bits to the Last Supper and Crucifixion story until it was about twenty-five minutes long, and it got me noticed. People started talking about it and came from miles away to see me do it.

It became hugely popular and it came to define me. It was the most extraordinary moment of my life, as far as comedy goes. But I had no idea any of that stuff would happen. I just thought it was funny. After the Last Supper sketch everything just grew and grew for me, over the next few weeks and months and years, and I sometimes think everything I’ve become since was because of that.

That was the first huge break for me. I understand that they are now thinking of putting a blue plaque in the Sarrie Heid about it. I hope it just says:

“THIS IS WHERE THE LAST SUPPER REALLY HAPPENED”

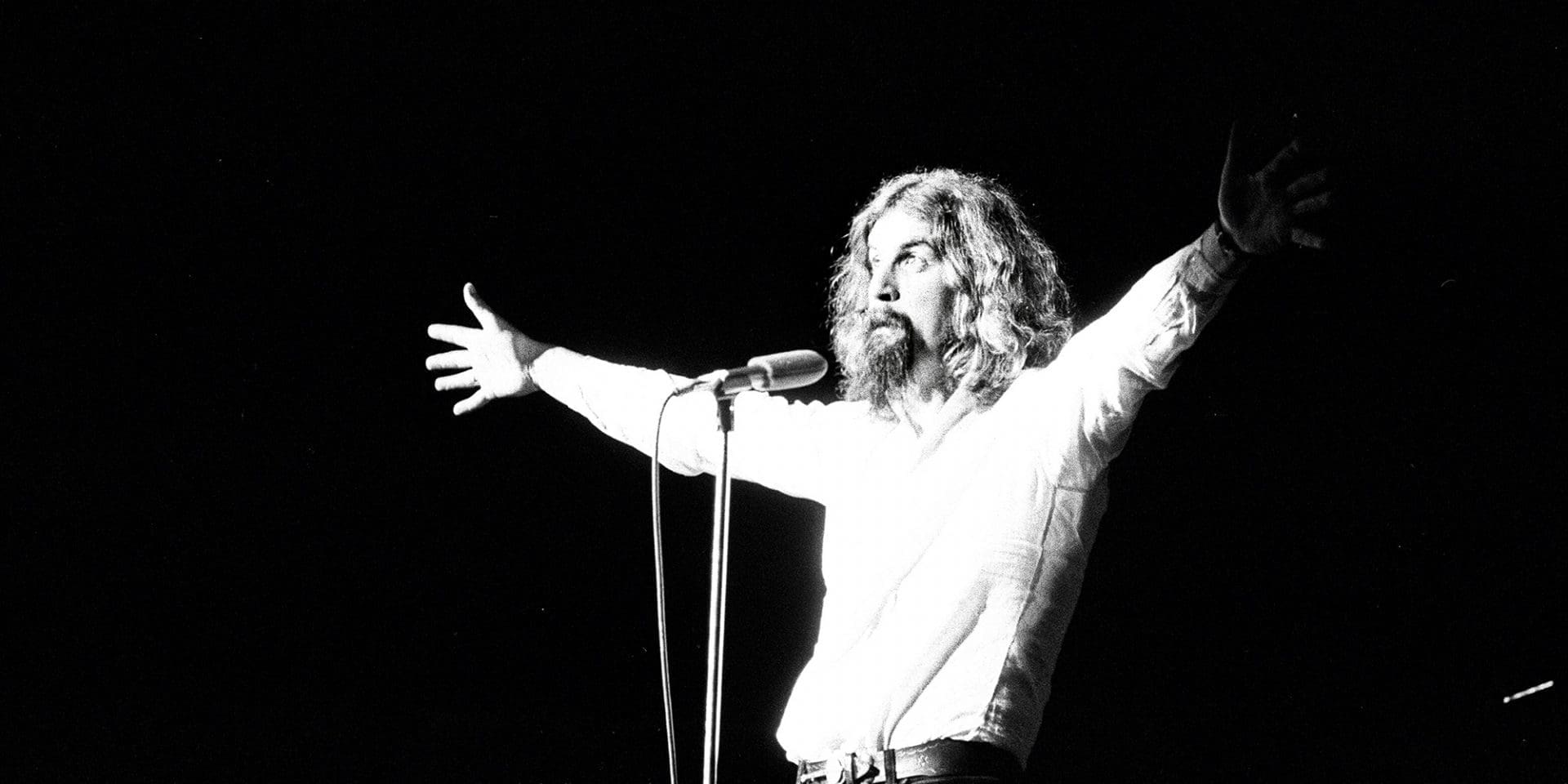

My influences were those other guys in the Scottish folk world that I loved, like Hamish Imlach and Matt McGinn, and the English guys like Jasper Carrott and Mike Harding, who were doing personal stuff and political stuff and generally just talking about whatever took their fancy. I wanted to emulate them and, even beyond that, I wanted to emulate the guys I’d met in the shipyards, the patter merchants who had made me howl with laughter. These were all guys who were being funny without telling jokes: who were funny about everyday things all around them and who took the piss out of people relentlessly. They refused to take life too seriously because they knew that you can volunteer to do that but it’s going to bite you on the arse. Because working-class life is harsh, and you can either break down and complain about how miserable your life is, or you can have a go at it and survive. And that’s the basis of what I do.

So, I just carried on doing shows where I was singing funny songs on the banjo and generally just chatting the same way I would chat to a mate in the shipyard or the pub. I would start to tell a joke, then get distracted into anecdotal stuff, then pick up the joke again, which felt perfectly natural to me. For some reason, people seemed to find it hysterically funny that I could leave a story for five or six minutes and then come back to it. I would try to explain to them: ‘When you talk to your pals in the street, you don’t proceed logically from one to ten in your conversation. It’s not A‑B‑C. The conversation wanders off and has a look around, and you change the subject when things occur to you! That’s all I’m doing.’

I didn’t have a technique for changing the subject. That’s not how my brain works. I would be talking about something in the joke and it would remind me of something else and I’d go off on a limb then come back again. My theory, if I had one, was to keep talking until I remembered what it was that I was talking about.

That was about as deep as it got. It was a mystery to me where it was all coming from. I never had notes, or a script. I might have a scrap of paper with a few words on it.

Nowadays, I have a stool with a glass top on stage, and it has my headlines on it. It might just say:

“ARMY

BROKE”

And that’s it. Lenny Henry told me he thought I had a computer with all my routines stored on it, but I havenae. I’ve always worked the same way, and happily, people seem to like it.