The First Great Wanderer

The potential of Virtual Reality has been a promise for a long time, but through the convergence of tech and the rise of the gaming industry, it’s looking more and more of a reality. Facebook’s shift to Meta and focus on the metaverse has reignited interest in the space amongst other players like Microsoft and Nvidia, but it’s not just the Silicon Valley tech giants that are shaping the future. A VR game developed out of New Zealand has been taking the world by storm.

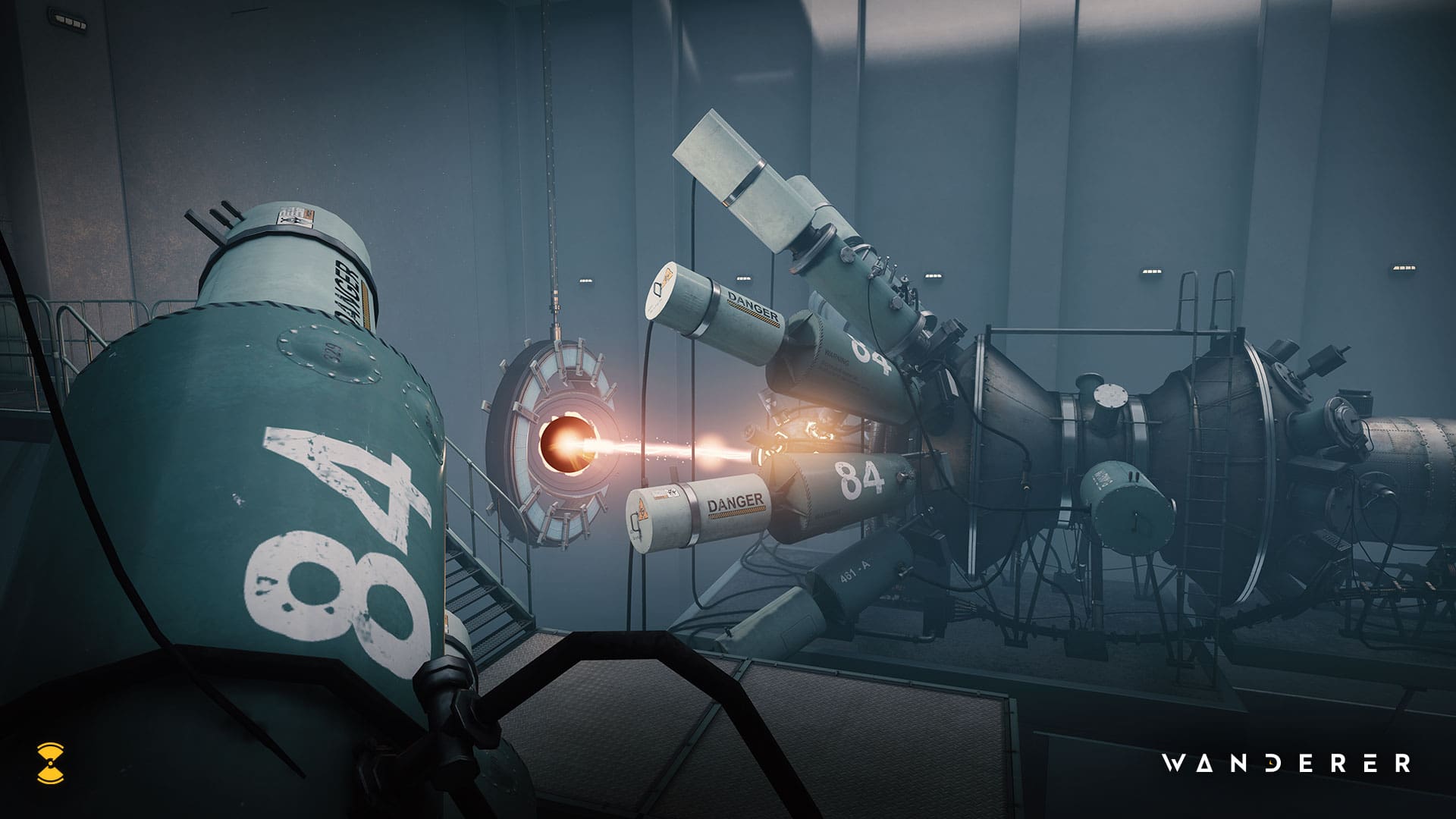

Wanderer is a time travelling adventure game that allows players to not only immerse themselves in an alternate future, but also famous moments from history, including the moon landing. It’s been a labour of love for the people behind Wanderer, including co-directors Euge Eastlake, Sam Ramlu, and Ben Markby, but they have taken a great story and grand vision and executed it into a VR experience that has achieved global acclaim. Ben Markby takes us behind the scenes.

The feedback and reviews for Wanderer have been amazing. Game reviewers seem to be a pretty prickly bunch at the best of times, but the response has been phenomenal. Was that something that you had expected?

To be fair, we were a little in the dark. I won’t go too much into the trials and tribulations of developing a game of this ambition, but it was a hard year, a really hard year. When you’re in the trenches like that, you lose a lot of objectivity.

We had a team of testers playing and received mixed reviews early on. You try to mitigate that by changing things and you do what you can to get the best possible product.

We knew how we felt about the game; we thought it was pretty good and we hoped it would appeal to people. It was something that was true to our hearts; it’s the game we wanted to play, it’s the game we wanted to make.

We got it out to reviewers a couple of days early and we started getting this feedback from them; ‘This is the best PlayStation VR game I’ve played all year’. I remember I was driving and I read that at a stop sign and I just thought, ‘holy hell’. I basically cried. I literally did cry.

I was really into Quantum Leap back in the 90s and this is a little bit like that.

The game is set in 2061 in a world that basically went to crap in the 1980s. It’s a frozen-in-time world where climate change happened way earlier and things went well off-kilter much earlier. You find yourself in this world and you start to understand what’s happened to it. You meet a few people and then the adventure begins and you eventually start time travelling to some of the greatest events and moments in history; you meet [Nikola] Tesla and all sorts of different people.

I’ve been heavily involved with VR for a long time. More so just as being a massive nerd. We always thought time travel and history was such an epic concept. Why wouldn’t you want to use VR for that? I love watching History Channel documentaries, but what if you could actually go there and, rather than being a fly on the wall, you could witness that. Not even just witness it, but take part in it and be a pivotal piece in that experience. That was the initial concept and from there, it evolved.

Do you feel like you were scratching the surface of something bigger as well? Does that start to change the potential of education?

Yeah, for sure. When we started the concept, a lot of it was for funding purposes, but it really did revolve around the educational side. We can put people in these moments and give people the emotion of what it was like to be in a moment. And then we started to realise, we could turn this into a product that you could play and it should be a game. I’ve always been a gamer and I’ve been making games for the last seven years.

We thought we’ll take a lesson from the franchise, Assassin’s Creed; those games are rooted in history. This is a crazy fact, but when Notre-Dame burned down a few years ago, do you know who they went to to get the most accurate model to rebuild that? Assassin’s Creed. It’s crazy.

We’re looking at that model in the sense of making a game that will appeal to the gaming fan bases, but it’s rooted in a context in history and something that can provide real value to players that play it. Not just scratching the surface of your Call of Duty’s and that kind of stuff, but a real immersive and engaging story. Something that can make people feel like they’re going on this wondrous adventure back through time in a way that’s executed so that there is an immersion level that feels like they are there.

How do you compete with those bigger studios with their bigger budgets?

It’s obviously difficult, but I think there are a couple of things there that work in the indie’s [game developers] favour. The big players take less risks and so that’s where the small teams can be a bit more creative and come up with ideas that big players just wouldn’t want to take a risk on.

The second thing is we purposely wanted to get into the VR market, because we felt that the big players in there weren’t doing a good enough job, it was underserved. We felt we could definitely make content for that market that would be in the top calibre. It seemed like a no-brainer for us.

I heard they spent $235 million making Grand Theft Auto?

Yes, that’s correct. They made that back four times in 24 hours.

Wow, that’s incredible. But how do you compete with that level and put out something that looks comparable?

You just don’t try to make that game. You don’t try to out-Grand Theft Auto, Grand Theft Auto; you don’t try to out-Call of Duty, Call of Duty; you don’t try to remake Fortnite.

I’ve been to a million game conventions, they always tell you this; don’t look at what’s trendy and what’s big. You need to find something that you’re passionate about and you need to find something that you know can stand on its own two feet in regards to an offering for an audience that is either underserved, or that you know you can compete in that market.

If you have the capital, then maybe give it a go, but you need to really understand the market and the product you’re trying to produce.

Can you talk about some of the moments along the way where you didn’t know how you were going to make it through the next month?

Oh, there are many. Making a game involves a lot of people, it’s a real orchestra of people. It involves just about every art form you can imagine; there are writers, voice artists, sculptors, musicians, programmers, designers. The list goes on forever. It is a small game and it has a long credit list.

For us, we went from zero to a hundred. We’d made some small mobile games. We’d made games for brands and then we suddenly got investment and got the opportunity to make this game. We now had to deal with making a game of this calibre and dealing with all the wonderful people you need to make something like this and manage that.

It was just a hundred miles an hour, just trying to keep the wheels on. VR is the Wild West right now, the rule books are gone. It’s a difficult medium to develop for, especially for a green company like we were. We really dived in the deep end.

There were some really challenging moments there with running out of money and not meeting our next milestones and facing technical issues. You’re trying to get the attention of all these people that might be able to help you and trying to formulate networks with engine programmers overseas. It was just insane.

How do you deal with that? You’ve got all these variables.

Well, it broke my business partner and he’s gone, so that was pretty gutting. I still have two more business partners, which we rely on heavily for support, but it was tough.

We’ve said to ourselves, we can’t do that again in that way. It’s a strange thing, it was the most fun I’ve ever had, but it was also some of the most horrible times I’ve ever had, really intense. The head of Studio Ghibli, which is a big animation house in Japan, says that every time they finish a movie, he thinks he never wants to do that again and then a few weeks later, he just can’t wait to start the next one. Some strange addiction there.

You cut a good steady job to move into a garage and start your studio. Can you talk through that process and that leap of faith?

I had run a few businesses prior, just on the side of working full time and to marginal success. I gave those up and was just working. My business partner and I did a little game concept together and we won a Best Award for it. So we thought, maybe we’re actually alright at this.

We’re sick of making stuff of value for other people, we thought we could probably just give this a crack. So we moved into his mum’s garage out in Howick and we had nothing at all. We had no backing, no money [laughs], we didn’t even have savings.

We just started taking a few odd jobs when we could and we shipped our first game that year. That game actually did pretty well and that gave us the opportunity to start and get an office and start hiring a few developers and go from there.

Can you talk about that game?

We built a game in 2016 called Jrump and it was a parody game in the theme of South Park about Donald Trump. We came up with the concept about four months before the US election. We knew we had to ship this game before the elections to really maximise the virality or the potential of it.

We built the game in 12 weeks, which was just crazy, and shipped it, and then it just went crazy. It was on the front page of Rolling Stone, front page of Huffington Post. We made the top 30 paid games in the US.

Wow. What was the gameplay?

It’s a stupid game, but basically, you’re Donald Trump and you’re trying to make the galaxy great again by fleeing earth. You have to draw his favourite thing in the world, which is walls <laughs>, underneath him and catch him as he is falling and dodge things he hates; scientists, other politicians, etc.

And then we did a follow-up to it called The Devil’s Ear. You ended up playing as Bernie Sanders and you could shoot tax returns at Donald Trump as a big boss battle.

I’ve read that we are looking at a billion-dollar industry in New Zealand by 2025, in terms of gaming export. That’s potentially a lot of jobs for a wide range of people. What do we need to do to support that and help it grow?

The tertiary institutions here are starting to offer better and better degrees. We have a lot of juniors coming through, a few seniors but there’s a massive gap f=or intermediates. I’m not really sure what the answer is there. We basically took on 80% juniors and just had to battle through it. That was again, one of the struggles.

I think educating kids at a younger age in school and really making them aware that game development is a bit like film. It has such a wide array of applications and so if you’re interested in being a sculptor or a writer or a musician, there’s a career path there for those things.

If you’re a musician, you don’t have to be out there Justin Beiber-ing it, you can make a really good living from making music for video games. Our music engineer and composer has started his own firm and he’s doing really well. He’s making music for a dozen games or so at the moment in New Zealand and it’s epic to be able to support him while he supports us.

I think that’s a big thing that’s happening in the industry here, this growth and this support that’s happening within the community.

Is there anything else about being in New Zealand that enables you to succeed?

I think it’s a hangover of colonialism, of being a young country. We’ve got this naive, cowboyish nature where we just go, ‘Oh, we’ll just give it a bloody go’. We don’t get too bogged down with people asking, what will happen if I do this or too many people telling us ‘no’?

It’s this naivety where we’re willing to jump into the deep end and give it a crack. Sure, we’ll make mistakes. We’ll fail here and there, but I think overall, we get a net positive from that and it means we punch way above our weight, especially creatively.

You look at our film industry, you look at what’s happening here in the game industry, our advertising industry. They punch so far above their weight on a global standard. It’s phenomenal.

Would you have any advice for someone who’s looking to leave their safe job and pursue their dream?

Cut the safety nets. That was the thing for me. Just give it a go, there’s no right time to do anything. You can make calculated decisions, but I think you’ve just got to look yourself in the mirror and say, ‘is this really what I want to do?’ and do it.

What’s your next project?

We’ve started our next phase already. I can’t talk about what that is, but we’ve got two things in early development and things underway for releasing products over the next three to five years.