Global Endeavours: The Quiet Giant Behind Some of New Zealand’s Biggest Beverage and Ingredient Brands

Behind some of the most recognisable beverage labels on New Zealand shelves and increasingly offshore is a business that has grown quietly, strategically, and with remarkable resilience. Global Endeavours, led by founder Hamish Gordon, is a vertically integrated group that spans commodity trading, contract manufacturing, and brand development. With operations across New Zealand and Australia, the group includes Natural Sugars, Pure Bottling, and Premium Liquor, supporting a client base that ranges from ambitious startups to major multinationals.

What makes Global Endeavours unique is not just its scale, but the way it’s been built. No VC capital, no shortcuts. Just cashflow-funded growth, relentless process improvement, and a willingness to take risks when the stakes were highest. From commodity hedging to the launch of breakout brands like Batched and Alchemy & Tonic, Hamish has built an empire from the ground up, starting in the depths of the GFC with a newborn baby and a 60-square-metre flat.

Hamish shares the backstory and how to build a company with staying power on the edge of the world.

Do you ever think about a sliding doors moment, like if you’d stuck with skydiving instructing as a career option?

Possibly. I realised that wasn’t for me, though. I suppose the real sliding doors moment was the opportunity to go in and start a business against a major corporate at the time. That was sort of make or break, right? I was 29 years old, and those opportunities don’t come around much. And as much as it was high risk, it was one that I knew if we could get it right, we could get a head start.

So it’s 2009, and you’ve got a stable job. You’re taking a leap. Can you talk a bit about the opportunity and what your mindset was going into it?

Yes. So I was working in food commodities, or food ingredients, from about 2005 to 2009. From 2007 to 2009 I was working for a company that was owned by a large multinational. But before I joined, it was 25% owned by a Kiwi CEO who had a two-year restraint of trade after he was bought out. That happened the Friday before I started on the Monday. So I didn’t know him then. But when his two years were up, he gave me a call and asked if I’d be interested in going into business.

Commodities are traded on the futures market and real time. So whatever the futures market closes at in the morning, and whatever the exchange rate is that day, that’s what you’re quoting customers. And when we went into business, the market was at 28-year highs. If it had turned, we would’ve been in and out pretty quickly. But we were lucky the market kept going up. We had strong relationships in the trade, and a lot of customers backed us. That was really the beginning.

I’ve heard you talk before about your 20s, pushing hard into commercial property and shares and then getting hit by 2008. Did that change how you thought about risk when starting the business? Were you carrying scars from that?

Yeah, totally. I mean, I was involved a couple of commercial property investments and we lost both tenants — they couldn’t pay rent because they were struggling. And then I thought, I’ll put money into the share market. You know, everyone says, “Go in with a diversified portfolio,” but in my 20s I was like, “No, here’s a couple of shares I really want to push.” And they both fell off a cliff. So when we went into business in 2009, my wife and I had our first boy that August, we were living in a 60 square metre rental, for a couple of years we were bathing our first two kids in a fish tub. So the risk felt very real. But I knew if I didn’t take it, we’d probably spend life on the back foot.

Do you remind your kids of that when they ask for new Nikes?

(Laughs) Yeah, a little bit. Our oldest is 15 now. They don’t ask much about those early days, but I’m sure they’ll be curious in time. For now, we just make sure their feet are on the ground. Things can change quickly.

So where are you now and what’s the scope of the business today?

Global Endeavours is a group of three major New Zealand businesses. We’ve got Natural Sugars, which we started in 2009. Then there’s Pure Bottling, which is a beverage manufacturing business we started in 2014. And then there’s Premium Liquor, our liquor company, which we started in 2018. Plus we’ve got Global Endeavours Australia, which represents the full group across the ditch.

We do everything from supplying sugar and oil into retail, food service, and industrial markets, to manufacturing beverages — from small startups to major multinationals and supermarket brands. We’ve got the most diversified bottling plant in New Zealand and the most globally accredited too.

It’s been a hell of a journey. The reward for doing well in manufacturing is usually having to buy more gear. So it’s capital-intensive. And the reason we started the liquor and beverage businesses was really to make sure we had reliable volume going through the plant.

From the outside, it almost looks like an octopus: different strands all connected. Was that part of the strategy?

Yes, ideally, you co-manufacture for a beverage company that takes a lot of sugar. That’s the dream. But things change, and as long as you’ve got volume moving through, and a good portion of your customers are buying multiple products or services from you, then you’re on solid ground.

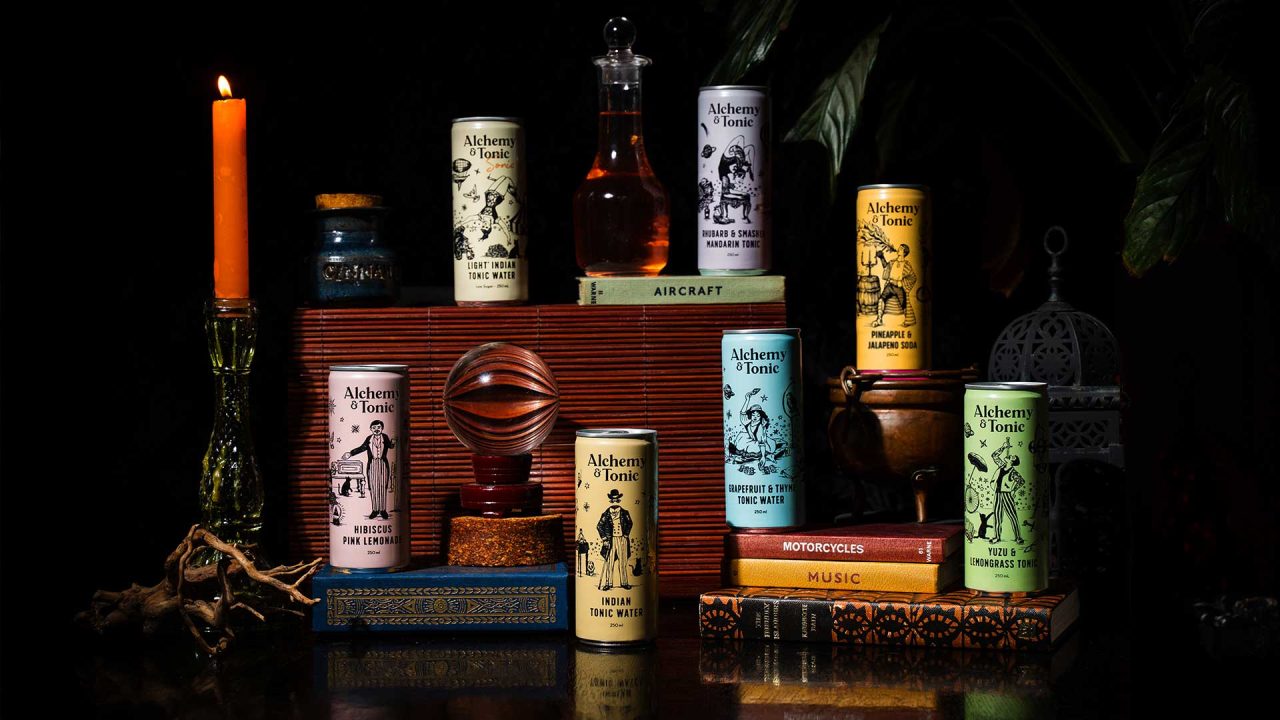

Take our brands like Alchemy & Tonic — they flow right through the system. The ingredients come from natural sugars, manufactured at Pure Bottling, and then distributed through either premium liquor or natural sugars. That’s true vertical integration.

There’s diversity in the revenue, but does it get complicated? Does it make it harder to focus as CEO?

It can do. I was literally in a meeting about this. The Natural Sugars side is the oldest and runs really well with great systems. Pure Bottling’s process-driven. But as we’ve grown, we’ve had to constantly upgrade systems and bring in new processes.

And you’ve got people who grow with the business and people who don’t. And it can be complicated even from the inside. The brands team doesn’t always understand the commodities team, and they don’t really care how the stuff is manufactured. They just want it done. That’s the nature of the beast.

But that’s the beauty of business too, you’ve got different people doing different things, all working toward a common goal. It makes it interesting.

Does that variety keep it exciting for you personally?

Yes, I get bored pretty easily. I need lots going on, that’s just how my brain works. A couple of years ago, we changed our ERP to Microsoft Dynamics. That was a nightmare, but it had to be done. You never hear good stories about system changes, but it’s helped us move forward.

What about automation and AI, obviously big topics right now, are they impacting how you operate?

Yes, definitely. We’re using CoPilot with Dynamics, and a bit of ChatGPT. Our factories are way more automated now. I mean, we had double the staff when we were doing a quarter of the volume we’re doing now. It’s a huge shift and we will continue to automate.

Now we’ve got fewer, but higher quality people, engineers, smart operators. And we’ve reduced human error with every new process we’ve introduced. Because New Zealand is not a cheap place to do business. We’ve got to be better, faster, smarter.

If we’re looking at the beverage market, margins are notoriously tight. Has that shifted at all now that you’ve gained more productivity through automation?

Yeah, a little bit, but costs don’t really go down. Infrastructure in New Zealand just keeps going up, power, water, waste management. I don’t even know if we’ll have gas in six or seven years. And then there’s wages. We aim to pay the living wage across the board.

I was in India recently, and a lot of staff there earn the equivalent of $140 Kiwi a month. They’re working six days a week for that. Meanwhile, we’re paying nearly that per day. So it’s a hard game. You try to create margin by doing something different, by value-adding. But you have to be efficient. It’s tough and incredibly competitive.

How do we compete on the world stage against those kinds of labour and cost dynamics?

Well, when you’re dealing with developed countries and you’re in food and beverage, New Zealand still has a very strong reputation. That counts for a lot. We’re mostly exporting into the Pacific Islands, Australia, Europe and Asia right now. We’re just landing our first orders of Batched, our premium cocktail range, into the U.S.

So we try to go after niche markets within larger ones. Even in places like India or China, where you’ve got this huge shift from middle class to wealthy consumers, there’s opportunity. But you still need to be competitive on price, you can’t be double what someone else is charging, even with the brand story.

Do you think the U.S.-style nationalism and protectionism will have a wider ripple effect with more countries following suit?

I think so. A lot of it started with COVID. Countries started looking inward and protecting their own supply chains and economies. But the world’s so interconnected now that there’s only so far that can go. I do think about tariffs a lot, if the U.S. puts 25%, 30%, 50% tariffs on some countries, that’s huge but with NZ having not imposed tariffs on the likes of the US the hit to us should be minimal.

But again, if you compare that to what we’re paying staff here versus India or China, the gap is massive. That’s where automation and AI could help; it’s the only real way to close that gap.

Are you optimistic about New Zealand’s future and our place in the world?

I am. I think our big opportunities lie in food, beverage, and tech. We’ve got a small population for our landmass, and we’re seen as one of the most beautiful, safe and least corrupt places on earth. That counts for a lot.

If we can consistently produce high-quality products, if “Made in New Zealand” becomes synonymous with excellence, like Swiss watches, then we’re in a great position. But we’ve got to maintain that standard. You only get one shot at reputation.

When you describe your business journey, it makes sense in hindsight, starting with commodities, moving into manufacturing, then brands. Was that clear to you early on?

The goal was always to build New Zealand brands and sell them to the world. That was the vision from the start. The path to get there wasn’t as clear. I started trading commodities because I enjoyed it. Then I got into manufacturing. I didn’t think I’d end up there, but once you’re in, it becomes about how to make it all work together.

And honestly, one of the things I love about business is connecting with people worldwide. I get to go places I’d never go as a tourist, experience different cultures, build real relationships. That’s been a really cool part of the journey.

Thinking back to that 60-square-metre apartment, do you feel different now regarding your relationship with risk?

Back then, we were living in a tiny place, bathing the kids in a fish tub. You want to get out of that. But after losing so much in the property market and shares in my 20s, I had a lot of self-doubt. I’d go through a period where even after launching the business, I wasn’t sure we’d make it.

I did the Icehouse course in 2015, and some of us are still catching up. One thing we always talk about is how, as a business owner, the risk is always on the table. Until someone buys you out or you raise serious capital, it’s on you. You just learn to manage it better. You build the muscle.

And it’s been a rough few years for business but does that mean, for those who’ve made it through, we’re going to be stronger on the other side?

I think so. Resilience is baked into it now. If you’ve survived the last three years, you’ve had to adapt, streamline, and build depth. But not everyone has made it. There’s been real damage out there to people’s health, to their balance sheets.

And this hasn’t just hit property or a specific industry. It’s been across the board. I haven’t seen anything quite like it in my lifetime, the finance company and sharemarket collapses in the late 2000s didnt have this widespread consumer impact that we have seen in the last couple of years.

It’s made me more empathetic. You see how much people are carrying staff, suppliers, and customers. Everyone’s stretched. But yeah, if you’ve made it through, you’re probably more battle-hardened and prepared for what’s next.

Do you have a bias toward the brand side, given your marketing background?

Yes, I do. But I also really love the B2B side, working with people, building solutions, having solid relationships. I probably get more joy out of helping another business solve a real problem than I do from a billboard or Instagram campaign.

That said, when a brand connects with consumers, when they get what you’re doing and want to be part of it, that’s pretty special. That’s the ultimate in business. But it’s hard to get right, especially in a crowded market.

And that’s the beauty of your structure, you’ve got the steady B2B engine and you can play the longer game with the brands.

Exactly. And we’ve done it all in reverse compared to most. A lot of founders start with a brand, outsource everything, raise capital, and try to scale fast. We built a commodities business first. That created cash flow. Then we built the manufacturing business, which we made viable by producing other people’s brands. In saying this it hasn’t been easy.

And only after that did we start creating our own brands. That meant we didn’t have to keep raising money or give away equity too early. We could fund it off the back of what we’d already built.

Do you think we’ve forgotten that playbook a bit in the current VC-heavy environment — build brand, raise cash, raise more, lose equity…?

Yes, 100%. We see it all the time. There are some amazing brands out there, but beverage is a brutal category. Margins are thin. And even when you land a big contract, say with a supermarket, if there’s no locked-in commitment, banks won’t fund against it.

Whereas in commodities, you’re working with futures contracts. There’s paper signed on both sides. That’s something the banks understand. And that’s a big difference when you’re trying to scale sustainably.

And with trends moving so fast, brands can rise and fall in months.

Exactly. We’ve lived that. Over the last six years, we launched around 20 brands. Some just never gained traction. Some looked amazing, tasted great — but didn’t move. Batched and Alchemy & Tonic connected right away and have held on. But others didn’t, and we were left clearing stock.

So now we’re focusing on four-five brands that are working. We’re putting our energy behind them. Less shallow innovation, more depth. It’s the only way to do it properly.

But you do need to keep experimenting, right? That’s part of staying relevant?

You do. But when a brand resonates, you can innovate within that brand, new flavours, seasonal releases, without creating something totally new every time. That’s what we’re doing with Batched and Alchemy. Customers expect something fresh, and they respond to it.

What’s your process when launching a new flavour or product? Is it market insights, gut feel, or both?

Bit of everything. We look at global trends, flavour profiles, packaging, what’s happening in places like the US, UK and Japan. We’ve got a marketing team, and we work with the right flavour houses to get things just right.

But at the end of the day, sometimes you’ve just got to get it into people’s hands. Market research is great, but nothing beats seeing whether people actually buy it, and then buy it again.

You can’t be everywhere, so how do you make sure the team reflects your values and approach in their own decision-making?

I think we’ve got a strong senior team that really cares. They take ownership. They’re process-driven. They want to do better every day. And I like to think we look after our people, and that flows both ways.

How would you describe yourself as a leader?

I try to empower people. I want them to make their role their own. But values are key. Integrity, accountability, and delivering for the customer, are non-negotiables. I think we’re pretty aligned as a team on that.

If you could go back now with everything you have learned to 2009, to that 60-square-metre apartment, about to take the leap, maybe wondering what the hell you were doing, what advice would you give yourself?

I think the phrase is “you don’t know what you don’t know,” right? And sometimes that’s a good thing. If I’d known how hard it was going to be, all the risk, the pressure, the sleepless nights, I might’ve second-guessed myself. But when you’re naïve, you just get on with it. I remember every single contract we landed in those early days, I’d be doing a little fist pump. Every customer mattered and still does. I didn’t take anything for granted.

That naïveté, that blind optimism, I think that’s what carries you in the beginning. It’s the same with having kids. If people told you how hard the first few years are, maybe you’d hesitate. But you just get on with it. And even when it’s tough, even when you’re bathing your kids in a fish tub and wondering how you’ll pay rent next month, there’s still something that keeps you going.

You don’t go into this kind of life expecting it to be easy. It’s never nine-to-five. You’re up at 2am or 3am thinking about challenges, solving problems. But every one of those things, every setback, every bit of pressure, it shapes you. Makes you better. Makes you stronger.

And I think, maybe not in a religious sense, but in a bigger picture sense, we’re meant to be tested. To be made better. Or some days worse. But if you keep putting one foot in front of the other, you’ll get through.